Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Attraction:

Outstanding two billion year old stromatolite bioherm in the beautiful setting of the Wyoming Snowy Range. Please preserve these for future generations and do not take any samples or damage these rocks.

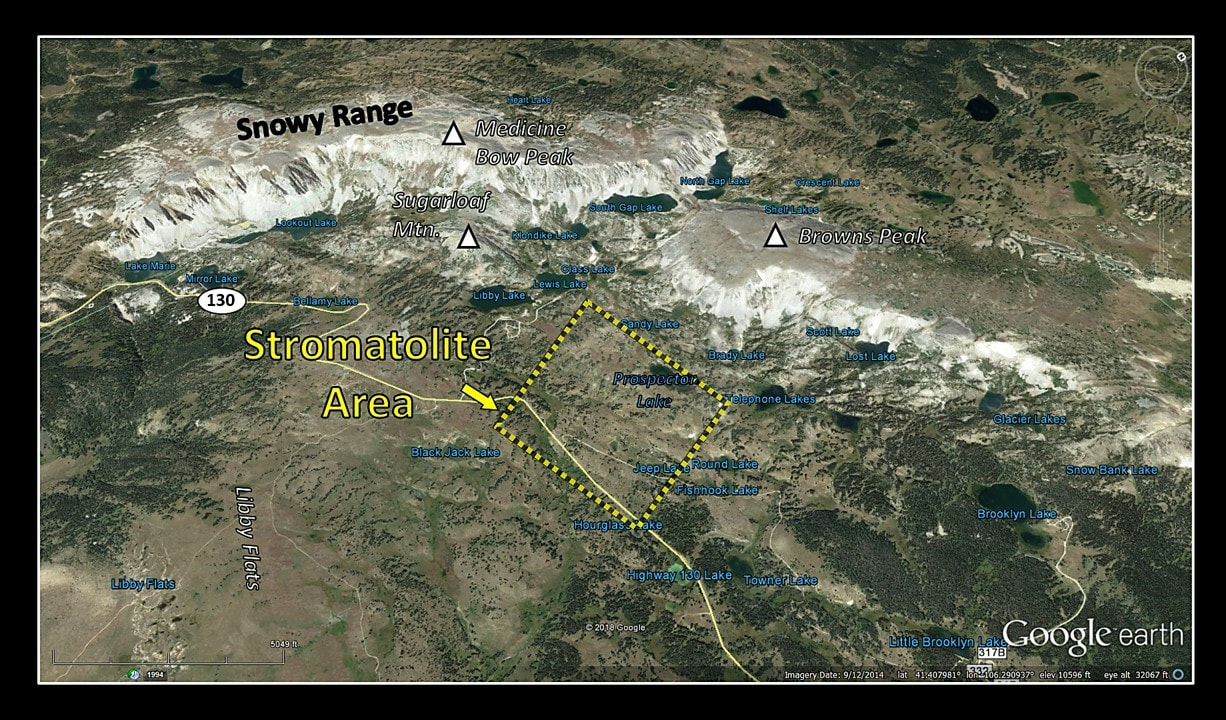

At the eastern base of the Snowy Range, along a glaciated plateau at 10,500-11,000 feet above sea level, are spectacular outcrops of Precambrian stromatolites. They are in 2-billion-year-old rocks of the Paleoproterozoic Nash Fork Formation.

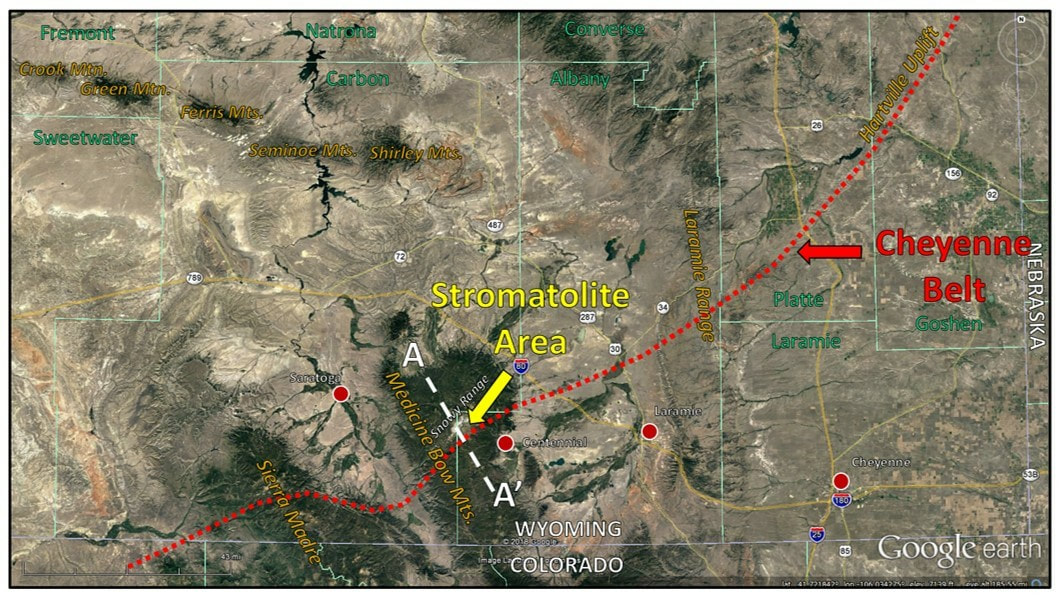

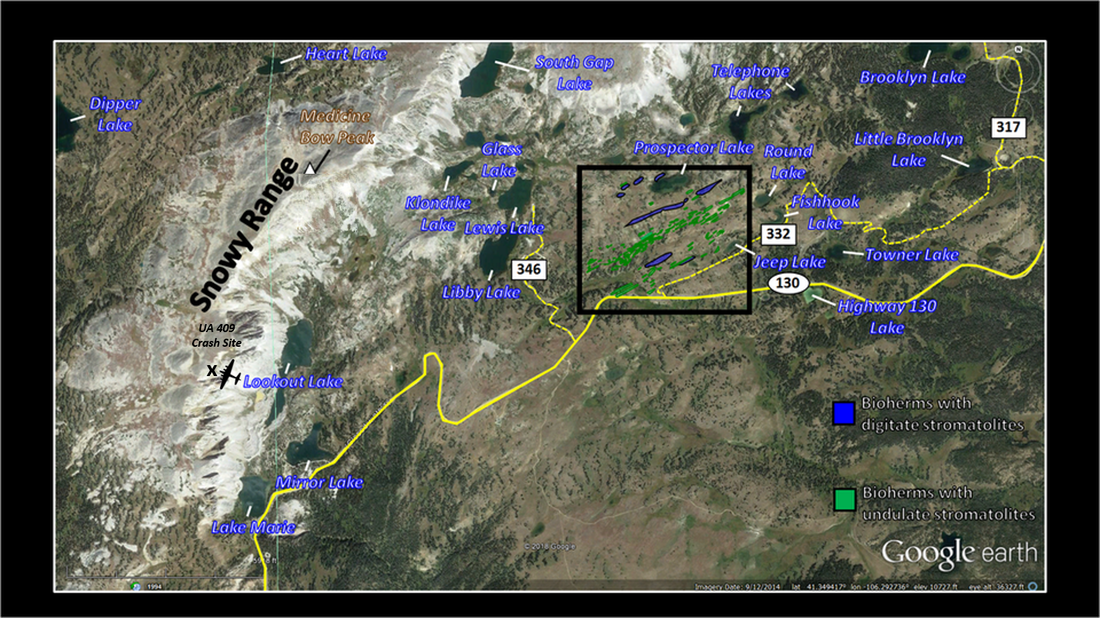

Northwest aerial view of Snowy Range and area of Precambrian stromatolite outcrops.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Stromatolites are layered structures produced by communities of microbial organisms that grow on sediment surfaces. Some of the organisms have filaments that intertwine, forming a sticky mat that protects the layer of sediment below from being washed away. When new sediment washes over the surface, filaments grow up through and over it to bind the new lamination. Boundstone is another name for rocks made this way.

Stromatolites range in time from about 3.5 billion years ago through the present. There are stromatolites growing today (the most famous being in Shark Bay, Australia and in the Bahamas).

“In the Beginning . . . . “

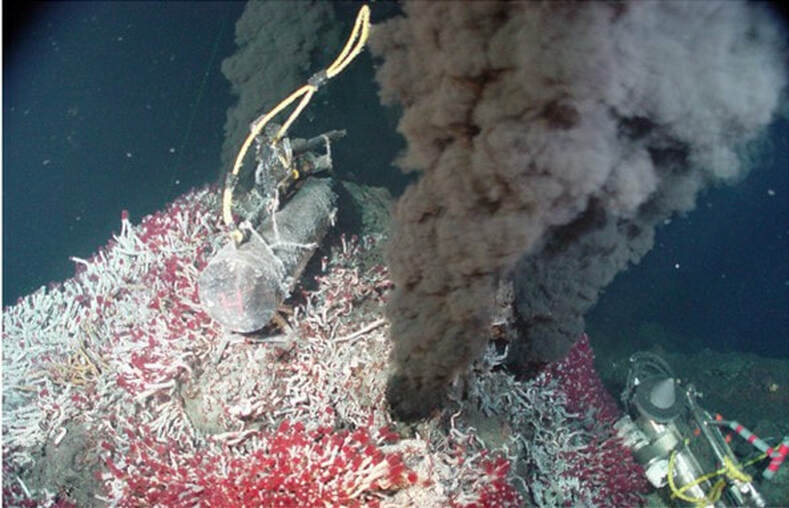

The earliest eon in Earth’s geochronology is informally called Hadean. It extends from the planet’s origin about 4.6 billion years ago (Ga) to the start of the Archean 4.0 Ga. Hadean was named after the Greek god of the underworld. Earth formed during the Hadean by the gravitational contraction of leftover dust and gas from formation of the Sun. Bombardment by asteroids, meteors and other debris added to the planet’s growth. The Sun’s radiation scorched the surface, since there was no atmospheric ozone to protect it. The temperature of the early Earth was about 3,300oF (1,800oC). The earliest atmosphere was composed of ammonia, methane and nitrogen (helium and hydrogen boiled away from the hot surface into space). Only a few fragments of Hadean age rocks (Nuvvuagittuq greenstone of Canada, 4.28 Ga) and minerals (zircons in the Jack Hills of Australia, 4.4 Ga) have been discovered and dated. Tiny inclusions of water preserved in ancient sand-sized zircon crystals show Earth had cooled enough to condense water vapor by 3.8 Ga. The condensing water rained down on the hot dry planet, gradually accumulating into oceans. The first undisputed evidence of life appears shortly after the end of meteor bombardment at about 3.5 Ga. These earliest organisms include anaerobic archaea that lived around underwater hydrothermal vents. The ocean they lived in did not contain oxygen, so they were adapted to anoxic conditions with high concentrations of methane and sulfide. In addition to microscopic fossils, they left biochemical traces that scientists can detect.

Stromatolites range in time from about 3.5 billion years ago through the present. There are stromatolites growing today (the most famous being in Shark Bay, Australia and in the Bahamas).

“In the Beginning . . . . “

The earliest eon in Earth’s geochronology is informally called Hadean. It extends from the planet’s origin about 4.6 billion years ago (Ga) to the start of the Archean 4.0 Ga. Hadean was named after the Greek god of the underworld. Earth formed during the Hadean by the gravitational contraction of leftover dust and gas from formation of the Sun. Bombardment by asteroids, meteors and other debris added to the planet’s growth. The Sun’s radiation scorched the surface, since there was no atmospheric ozone to protect it. The temperature of the early Earth was about 3,300oF (1,800oC). The earliest atmosphere was composed of ammonia, methane and nitrogen (helium and hydrogen boiled away from the hot surface into space). Only a few fragments of Hadean age rocks (Nuvvuagittuq greenstone of Canada, 4.28 Ga) and minerals (zircons in the Jack Hills of Australia, 4.4 Ga) have been discovered and dated. Tiny inclusions of water preserved in ancient sand-sized zircon crystals show Earth had cooled enough to condense water vapor by 3.8 Ga. The condensing water rained down on the hot dry planet, gradually accumulating into oceans. The first undisputed evidence of life appears shortly after the end of meteor bombardment at about 3.5 Ga. These earliest organisms include anaerobic archaea that lived around underwater hydrothermal vents. The ocean they lived in did not contain oxygen, so they were adapted to anoxic conditions with high concentrations of methane and sulfide. In addition to microscopic fossils, they left biochemical traces that scientists can detect.

A bed of tube worms surrounds a hydrothermal vent. Some of the earliest evidence for life comes from hydrothermal vent deposits.

NOAA image: http://www.planetary.org/multimedia/space-images/spacecraft/hyrdothermal-vent-and-tube.html

NOAA image: http://www.planetary.org/multimedia/space-images/spacecraft/hyrdothermal-vent-and-tube.html

Layered stromatolites are the earliest evidence of life that does not require microscopes or geochemical analysis to find. Although the earliest stromatolites formed in anoxic conditions as long ago as 3.5 Ga, the Snowy Range stromatolites grew in shallow marine water 1.5 billion years later, during the transition from anoxic to oxygenated oceans.

Geology of Snowy Range Stromatolites

The Snowy Range is a seven-mile-long northeast trending subrange in the Medicine Bow Mountains created during the Laramide Orogeny (70-50 Ma). The area is composed of Archean gneiss overlain by more than eight miles of metasediments of the Proterozoic Snowy Pass Supergroup. The metasediments were deposited in the ocean on the southern edge of the Wyoming craton about 2.5 to 2.0 billion years ago. They were folded between the Wyoming craton and the Colorado Orogen along the Cheyenne Belt tectonic suture about 1.78-1.74 billion years ago. The nearly vertical beds of metasediments uniformly strike north 55 degrees east and dip about 80 degrees to the southeast.

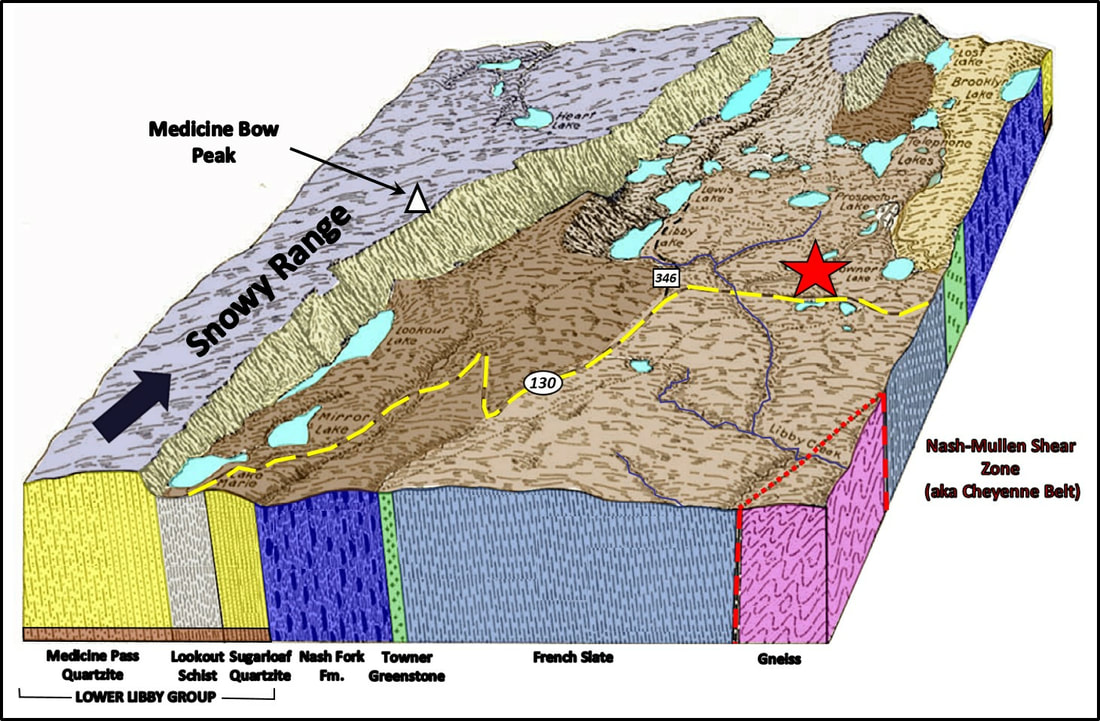

Physiography and subsurface geology of the Snowy Range stromatolite field. Stromatolite locality shown by red star.

Image: After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2), Plate 1, p. 75.

Image: After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2), Plate 1, p. 75.

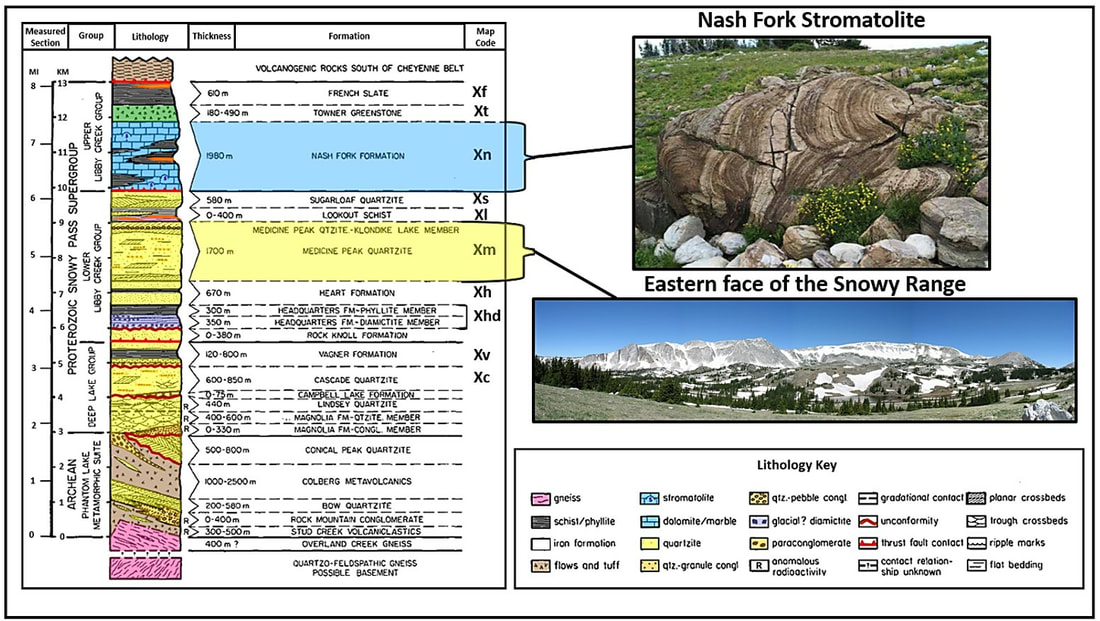

At 12,013 feet, Medicine Bow Peak is the highest point in the range. The 6,000-foot-thick Medicine Peak Quartzite (Xm) is exposed at the crest of the range. The Nash Fork Formation (Xn) is a 6,500-foot-thick tan siliceous carbonate (metadolomite) with thick lenses of black phyllite. Phyllite is slate that has metamorphosed with mild heat and pressure. Thin beds of interlayered quartz, chert, and iron-formation are less common.

The carbonate is characterized by stromatolitic bioherms and reefs ranging from a few feet in area to several thousand feet long and 200 feet thick. (Bioherms are large mound-like structures built by marine organisms. Biologic reefs are larger, wave-resistant structures built by organisms.) The Snowy Range stromatolites stand out in relief above the surrounding phyllite due to their greater resistance to glacial scour and erosion.

The carbonate is characterized by stromatolitic bioherms and reefs ranging from a few feet in area to several thousand feet long and 200 feet thick. (Bioherms are large mound-like structures built by marine organisms. Biologic reefs are larger, wave-resistant structures built by organisms.) The Snowy Range stromatolites stand out in relief above the surrounding phyllite due to their greater resistance to glacial scour and erosion.

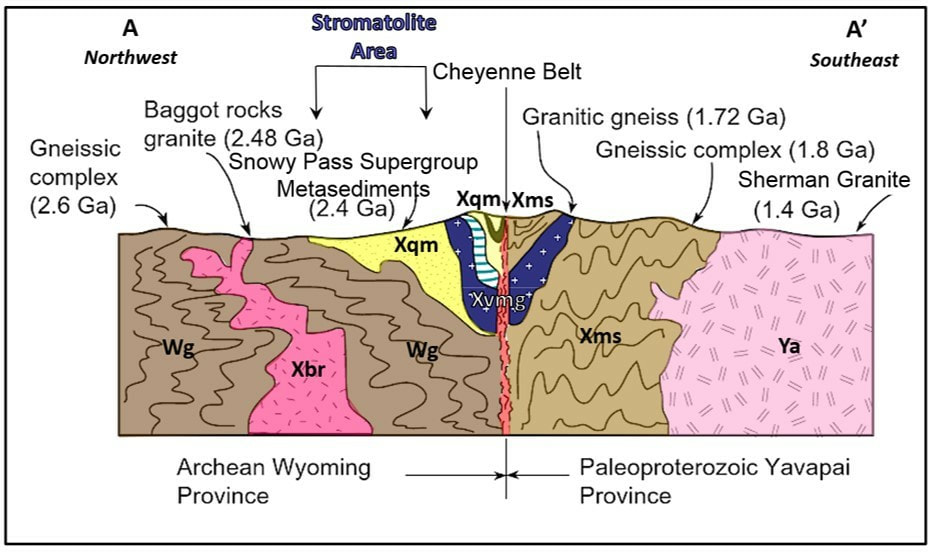

Diagrammatic cross section across the Cheyenne Belt tectonic suture. Geologic code (Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2004):Ya: Neoproterozoic Sherman Granite, Xvmg: Paleoproterozoic quartz-plagioclase gneiss, Xms: Paleoproterozoic mafic intrusive rocks, Xqm: Paleoproterozoic metasedimentary rocks containing stromatolites, Xbr: Paleoproterozoic Baggot Rocks granite, Wg: Late Archean red-pink gneiss.

Image: Top: After Condie, K.C., 2016,Earth as an Evolving Planetary System, Third Edition,Chapter 2, Fig. 2.25, p. 40; Bottom: Google Earth.

Image: Top: After Condie, K.C., 2016,Earth as an Evolving Planetary System, Third Edition,Chapter 2, Fig. 2.25, p. 40; Bottom: Google Earth.

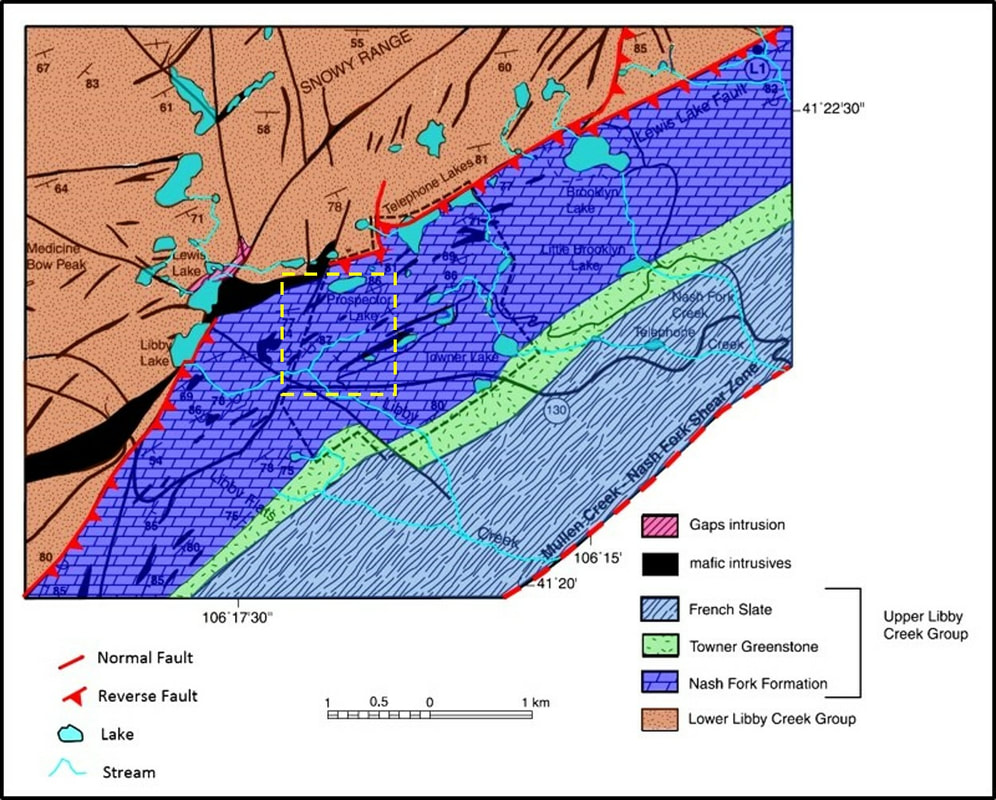

Geologic map of the Snowy Range stromatolite area. Rectangle shows area of bioherms and boundstones.

After Bekker and Eriksson, 2003, A Paleoproterozoic drowned carbonate platform on the southeastern margin of the Wyoming Craton: a record of the Kenorland breakup, Precambrian Research 120, Figure 3, p. 333.

After Bekker and Eriksson, 2003, A Paleoproterozoic drowned carbonate platform on the southeastern margin of the Wyoming Craton: a record of the Kenorland breakup, Precambrian Research 120, Figure 3, p. 333.

Snowy Range stromatolite bioherm area. Undulate stromatolites (green) are the dominant morphology and are characterized by horizontally layered growth forms. Digitate stromatolites (blue) exhibit dominantly vertical growth forms. Rectangle is area of closeup view of bioherms shown below. The site of the 1955 United Airlines DC-4 plane crash is shown by the airplane symbol (41º 20' 42"N, 106º 19' 45"W). It struck the eastern side of the Snowy Range just below the crest, and to the west of Lookout Lake.

Image: Google Earth; Data: MJD, 2016, slide 26, https://www.slideshare.net/michaeljdelvaux/denver-area-geology

After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2)

Image: Google Earth; Data: MJD, 2016, slide 26, https://www.slideshare.net/michaeljdelvaux/denver-area-geology

After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2)

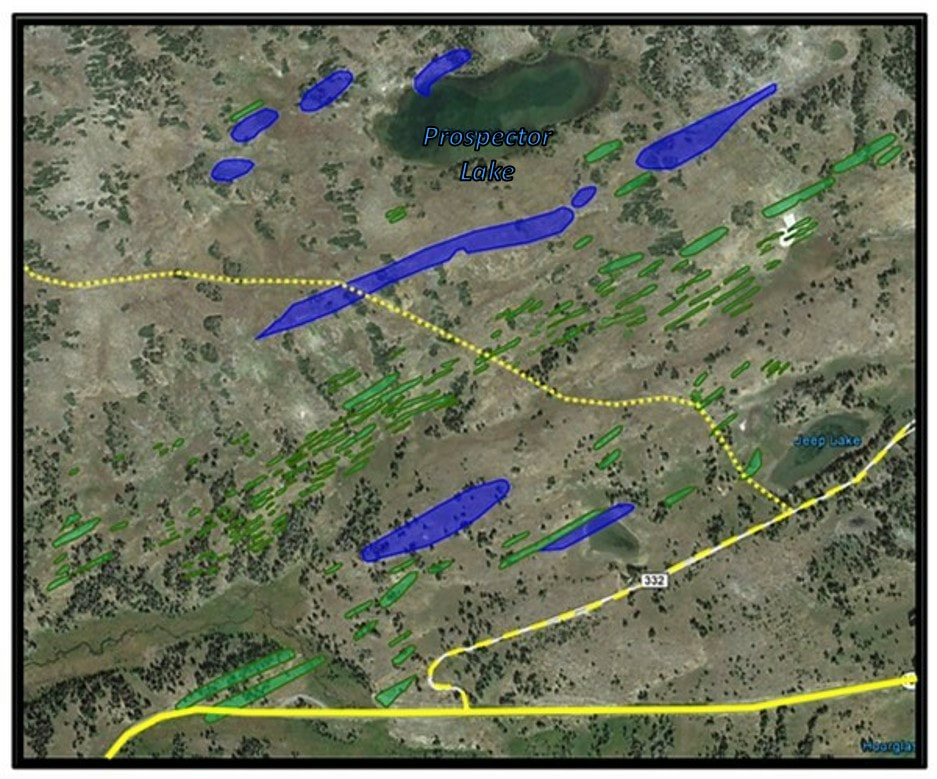

Closeup image of Nash Fork Formation bioherms. Area shown is within rectangle on previous map. Roads are shown by yellow lines: paved (solid), unpaved (dashed).

Image: Google Earth; Data: MJD, 2016, slide 26, https://www.slideshare.net/michaeljdelvaux/denver-area-geology,After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2)

Image: Google Earth; Data: MJD, 2016, slide 26, https://www.slideshare.net/michaeljdelvaux/denver-area-geology,After Knight, S.H., 1968, Precambrian stromatolites, bioherms and reefs in the lower half of the Nash Formation, Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Rocky Mountain Geology 7 (2)

Stratigraphic column of the Precambrian metasediments in the Medicine Bow Mountains.

Image: After Karlstrom, K.E., Flurkey, A.J., and Houston, R.S., 1983, Stratigraphy and depositional setting of the Proterozoic Snowy Pass Supergroup, southeastern Wyoming: Record of an early Proterozoic Atlantic-type cratonic margin: Geological Society of America Bulletin, Vol. 94, ;Stromatolite Photo: Boyd, D.W., and Lageson, D.R., 2014, Self-guided walking tour of Paleoproterozoic stromatolites in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular 45,Fig. 21, p. 12, http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/self-guided-walking-tour-of-paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-in-the-medicine-bow-mountains-wyoming-2014/; Snowy Range Photo: Marriott, H., 2012, In the Company of Plants and Rocks, http://plantsandrocks.blogspot.com/2012/03/there-is-one-bed-of-bright-emerald.html

Image: After Karlstrom, K.E., Flurkey, A.J., and Houston, R.S., 1983, Stratigraphy and depositional setting of the Proterozoic Snowy Pass Supergroup, southeastern Wyoming: Record of an early Proterozoic Atlantic-type cratonic margin: Geological Society of America Bulletin, Vol. 94, ;Stromatolite Photo: Boyd, D.W., and Lageson, D.R., 2014, Self-guided walking tour of Paleoproterozoic stromatolites in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular 45,Fig. 21, p. 12, http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/self-guided-walking-tour-of-paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-in-the-medicine-bow-mountains-wyoming-2014/; Snowy Range Photo: Marriott, H., 2012, In the Company of Plants and Rocks, http://plantsandrocks.blogspot.com/2012/03/there-is-one-bed-of-bright-emerald.html

Stromatolites exhibit several growth forms, but two types dominate in the Snowy Range area, digitate and undulate. Digitate morphologies develop mainly vertical lobate columns. Undulate forms are characterized by horizontally continuous flat to wavy layers. The morphologies are related to mechanical action of waves, water depth and the species of organisms that form the stromatolite. In addition, deformation at the time of deposition and during later tectonic movement affected the shapes of the features.

Snowy Range stromatolites have primary morphologies like these examples. Quarter shown for scale.

Image: After Geological Digressions, 2018, Atlas of sediments and sedimentary structures: Stromatolites and cryptalgal laminates, https://www.geological-digressions.com/atlas-of-sediments-and-sedimentary-structures-stromatolites-and-cryptalgal-mats/.

Image: After Geological Digressions, 2018, Atlas of sediments and sedimentary structures: Stromatolites and cryptalgal laminates, https://www.geological-digressions.com/atlas-of-sediments-and-sedimentary-structures-stromatolites-and-cryptalgal-mats/.

Atmospheric Evolution

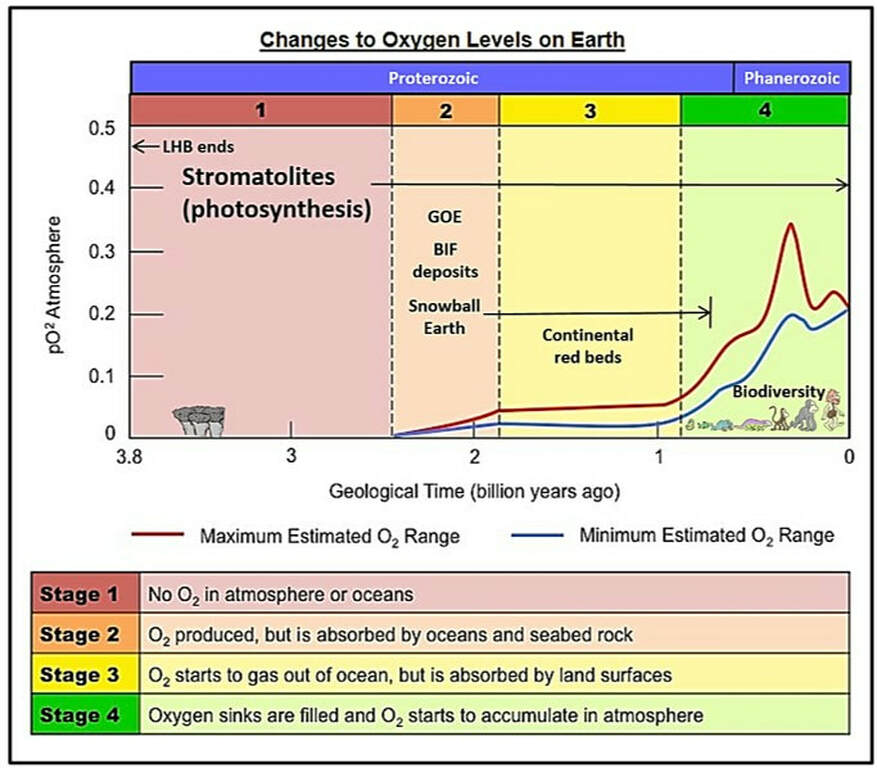

Stromatolites were critical to the development of Earth’s atmosphere because some of the Cyanobacteria that lived in their microbial communities produced oxygen as a waste product of photosynthesis. Although other bacteria perform simpler photosynthesis, only Cyanobacteria split water molecules to release oxygen during photosynthesis. They modified the chemical environment they lived in, at first just in thin layers near their filaments. The chemical change near the filaments facilitated deposition of carbonate minerals there, contributing to the preservation of stromatolite laminations.

Oxygen was toxic to most anaerobic early organisms. As oxygen accumulated in microbial mats, many organisms associated with the Cyanobacteria died. This probably allowed the photosynthetic Cyanobacteria to proliferate, increasing the production of oxygen. The earliest photosynthesis is difficult to date, but appears to have been about 3 Ga. Since then, oxygen has accumulated in the atmosphere to its current level of about 21%.

The presence of free oxygen changed the chemistry of the oceans and atmosphere. It led to mass extinction of many anaerobic life forms. For millions of years, the oxygen released in the ocean reacted with iron and sulfide, resulting in deposition of banded iron deposits. Later, oxygen released in the atmosphere rusted iron minerals exposed in surface rocks, creating Proterozoic red beds. The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) is when significant free oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere at about 2.4 Ga.

The GOE had two consequences. First, free oxygen decreased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere enough to trigger the Earth’s first glacial period (Huronian, 2.4-2.1 Ga). This Proterozoic glacial period is referred to as Snowball Earth. Secondly, the GOE increased aerobic biodiversity by allowing organisms adapted to oxygen to flourish and expand beyond the microbial mats to new oxygenated habitats.

Oxygen was toxic to most anaerobic early organisms. As oxygen accumulated in microbial mats, many organisms associated with the Cyanobacteria died. This probably allowed the photosynthetic Cyanobacteria to proliferate, increasing the production of oxygen. The earliest photosynthesis is difficult to date, but appears to have been about 3 Ga. Since then, oxygen has accumulated in the atmosphere to its current level of about 21%.

The presence of free oxygen changed the chemistry of the oceans and atmosphere. It led to mass extinction of many anaerobic life forms. For millions of years, the oxygen released in the ocean reacted with iron and sulfide, resulting in deposition of banded iron deposits. Later, oxygen released in the atmosphere rusted iron minerals exposed in surface rocks, creating Proterozoic red beds. The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) is when significant free oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere at about 2.4 Ga.

The GOE had two consequences. First, free oxygen decreased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere enough to trigger the Earth’s first glacial period (Huronian, 2.4-2.1 Ga). This Proterozoic glacial period is referred to as Snowball Earth. Secondly, the GOE increased aerobic biodiversity by allowing organisms adapted to oxygen to flourish and expand beyond the microbial mats to new oxygenated habitats.

Oxygenation of the Earth and benchmark events. Abbreviations: LHB: Late Heavy Bombardment (4.1-3.8 Ga), GOE: Great Oxidation Event 2.44-2.33 Ga), BIF: Banded Iron Formation (2.5-1.8 Ga).

Image: After http://ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-2-molecular-biology/29-photosynthesis/oxygenation-of-earth.html.

Image: After http://ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-2-molecular-biology/29-photosynthesis/oxygenation-of-earth.html.

Things-To-Do

The Snowy Range stromatolitic bioherm locality provides the opportunity to visit a place where some of the earliest photosynthetic organisms began profoundly transforming the chemistry of Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. Don Boyd and Dave Lageson wrote an excellent self-guided tour of the stromatolite area that can be downloaded free from the Wyoming State Geological Survey: (http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/self-guided-walking-tour-of-paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-in-the-medicine-bow-mountains-wyoming-2014/). Please do not damage the stromatolites or collect specimens. Please save them for future visitors!

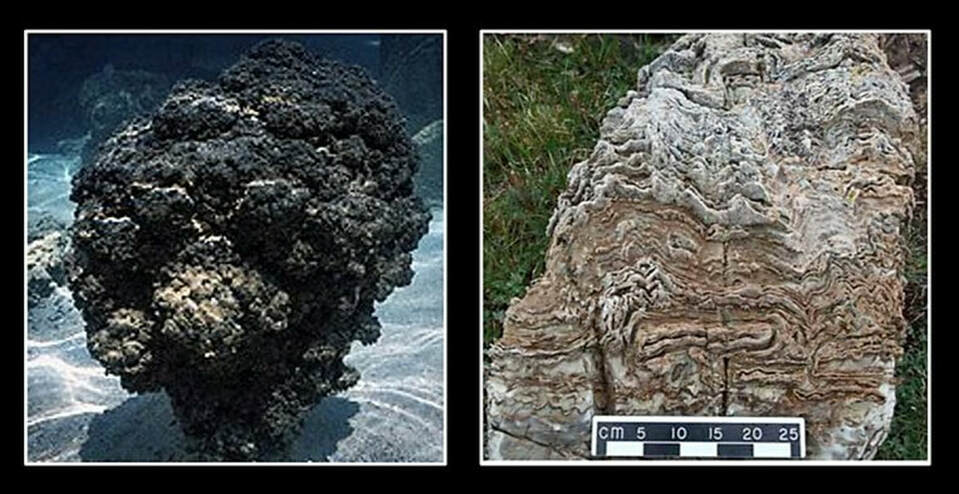

Left: Living microbes building a stromatolite from Hamelin Pool, at Shark Bay, Western Australia; Right: Silicified fossil stromatolite in the Nash Fork Formation at “Valley of Stromatolites,” Snowy Range stromatolite field, Southeastern Wyoming.

Image: Left: http://stromatolites.blogspot.com/; Right: Boyd, D.W., and Lageson, D.R., 2014, Self-guided walking tour of Paleoproterozoic stromatolites in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular 45,Fig. 25, p. 12, http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/self-guided-walking-tour-of-paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-in-the-medicine-bow-mountains-wyoming-2014/

Image: Left: http://stromatolites.blogspot.com/; Right: Boyd, D.W., and Lageson, D.R., 2014, Self-guided walking tour of Paleoproterozoic stromatolites in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular 45,Fig. 25, p. 12, http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/self-guided-walking-tour-of-paleoproterozoic-stromatolites-in-the-medicine-bow-mountains-wyoming-2014/

The material on this page is copyrighted