Triassic Chugwater on road to Canyon Middle Fork of Powder River

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (2 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Isolated wild canyons and valleys with steep walls and outstanding, scenic red rock formations.

Red Wall country is adjacent to the Middle Powder River at the southeastern end of the Bighorn Mountains. It is an area rich in history of native people, cattle barons, homesteaders and outlaws. The area lies within the BLM’s Middle Fork Powder River Recreation Area. The landscape was the palimpsest of tales of Indian trails and warfare, Dull Knife Battlefield, Hole in the Wall, Outlaw Cave, and the Johnson County War. It is a land of colored canyons and hidden valleys of breathtaking scope. It is an iconic landmark of the American West.

West view of the Canyon of The Middle Fork of the Powder River. Stratigraphic column of exposed rocks to the left of the image. The top of the Tensleep Sandstone outcrop bench is shown by white dashed line. The top of the Madison Limestone outcrop bench is shown by white dotted line. Red color on the stratigraphic column indicates unconformities (gaps) in outcrop sequence. Dominant vegetation contrast on opposite canyon walls is noted.

Image: BLM Wyoming, 2015, Middle Fork Powder River Canyon 1; https://www.flickr.com/photos/134389515@N06/25122708227/in/album-72157692088519564/

Image: BLM Wyoming, 2015, Middle Fork Powder River Canyon 1; https://www.flickr.com/photos/134389515@N06/25122708227/in/album-72157692088519564/

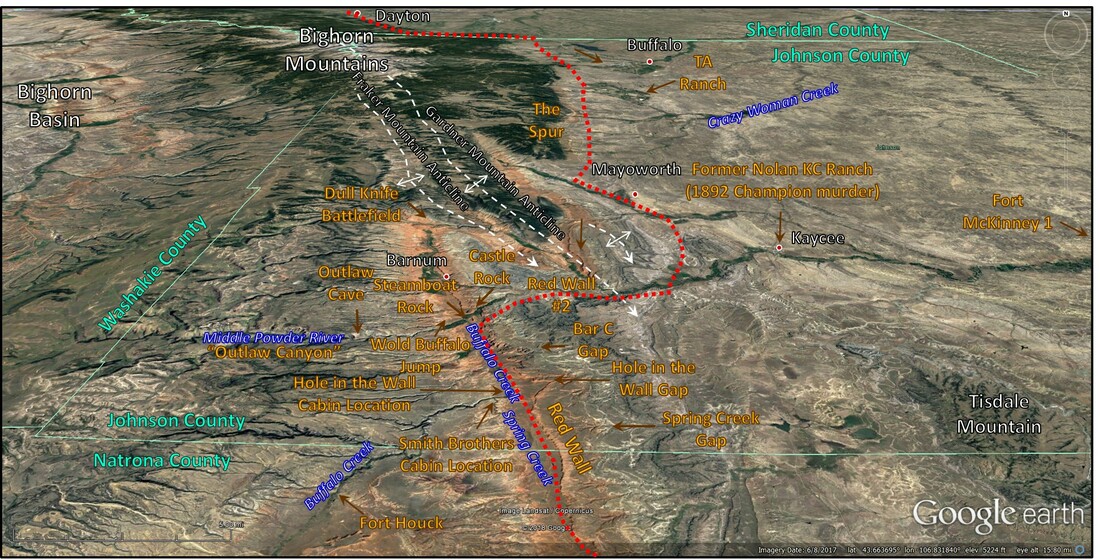

Aerial image of the Hole in the Wall – Red Wall area, Middle Fork Powder River Recreation Area. Several dwelling structures located between the Smith Brothers cabin and the those on the Willow Creek Ranch site were used by the Hole in the Wall Gang members. A small contingent of soldiers were stationed at Fort Houck, located on the Willow Ranch, for protection of the Kaycee to Arminto stage line. It also served as the area Post Office. The soldiers inscribed their names in caves in the area. The Spur is the southernmost outcrop of Archean rocks. The approximate route of the Sioux Trail shown by red dotted line.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Johnson County History

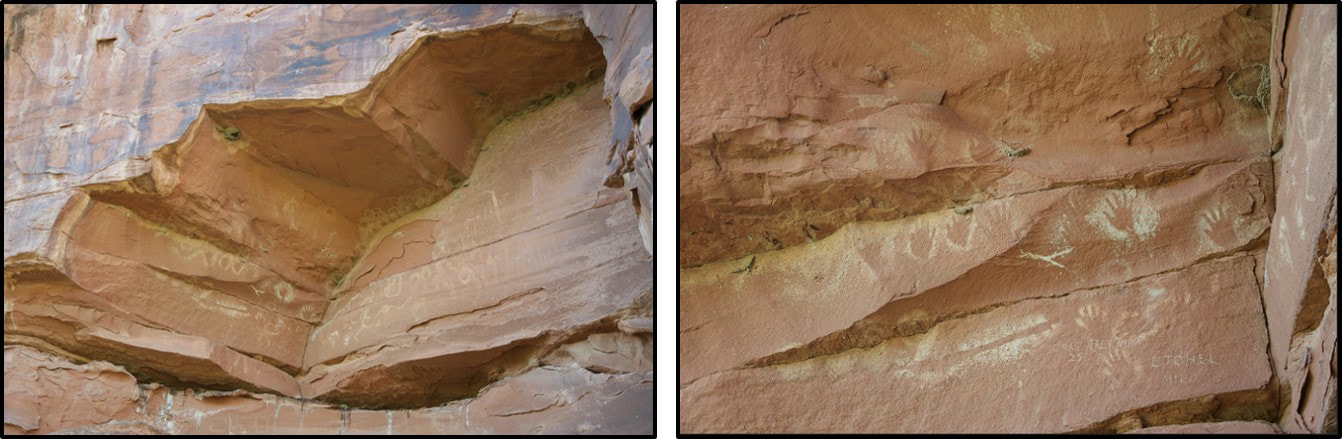

After the reintroduction of horses to North America by the Spanish in the 16th century, the Lakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne abandoned agriculture for nomadic buffalo hunting. A mid-1970s archaeological survey of the area discovered 84 prehistoric sites along the Middle Fork and Beaver Creek that would be flooded if a proposed dam were constructed. Julie Francis, lead survey archaeologist, believes people lived along the Middle Fork for the last 10,000 years. The natives important migration routes were often marked with rock cairn lines. The “Sioux Trail” across the Bighorns, and south along the eastern flank of the range has a line of rock towers from Dayton, Wyoming to beyond Hole in the Wall along Buffalo Creek. The Bar C cairn line is part of the Sioux Trail and consists of 98 rock piles, 2-15 feet in diameter, standing a few inches to 4 feet high (The Wyoming Archaeologist, 1959, Vol. II, No. 10, p. 4-5).The Wold Bison Jump is a geologic outcrop that native Americans used to help with hunting. Bison were herded over a cliff of Permian Goose Egg Formation, then were killed and butchered to feed the hunters.

Signs of native people’s presence. Left: petroglyphs on Tensleep Sandstone; Right: close-up view.

Image: Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-in-the-Wall Trip; Left: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sbeebe/6287863040/in/photostream/; Right: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sbeebe/6287344667/in/photostream/

Image: Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-in-the-Wall Trip; Left: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sbeebe/6287863040/in/photostream/; Right: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sbeebe/6287344667/in/photostream/

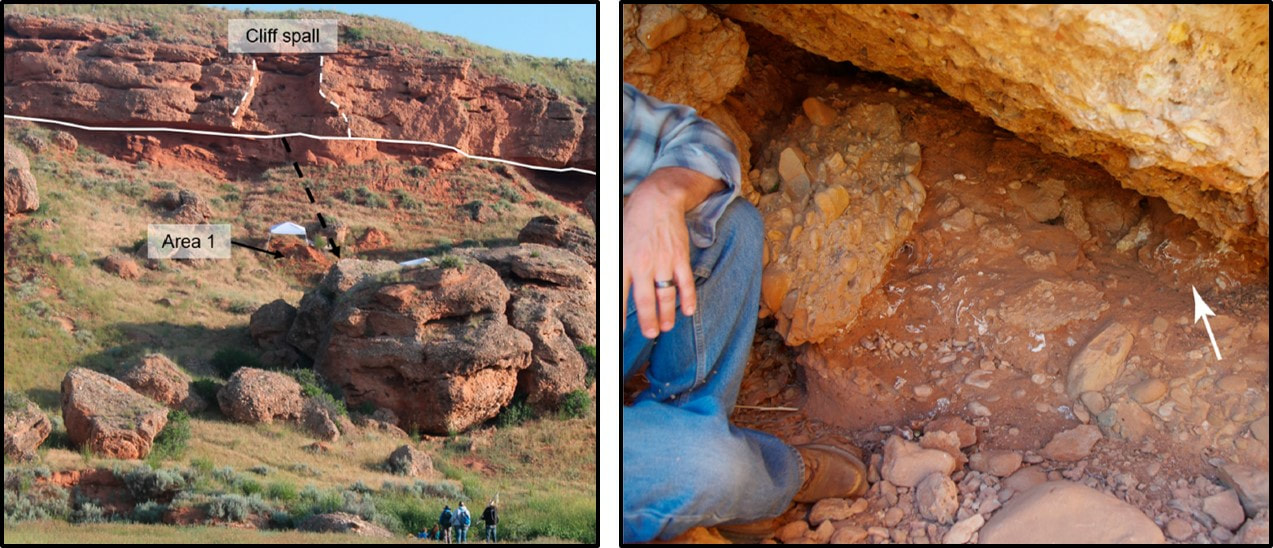

Wold Bison Jump along Middle Fork of the Powder River. The rock units consist of Quaternary terrace gravels and cobbles overlying the Permian Goose Egg Formation. Bison were driven over the cliff, killed and butchered to feed the hunters and their families. White arrow points to a portion of a bison skull with a horn preserved.

Image: Pelton, S.R., Shimek, R.L., Grund, B., Mackie, M., and Surovell, T.A., 2018, The Wold Bison Jump (48JO966) and its relation to the ancestral Crow on the Northwest Plains: Plains Anthropologist, Fig. 3, p. 5 & Fig. 4, p. 7; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Spencer_Pelton/publication/325094159_The_Wold_Bison_Jump_48JO966_and_its_relation_to_the_ancestral_Crow_on_the_Northwest_Plains/links/5af5ef330f7e9b026bcedfa2/The-Wold-Bison-Jump-48JO966-and-its-relation-to-the-ancestral-Crow-on-the-Northwest-Plains.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

Image: Pelton, S.R., Shimek, R.L., Grund, B., Mackie, M., and Surovell, T.A., 2018, The Wold Bison Jump (48JO966) and its relation to the ancestral Crow on the Northwest Plains: Plains Anthropologist, Fig. 3, p. 5 & Fig. 4, p. 7; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Spencer_Pelton/publication/325094159_The_Wold_Bison_Jump_48JO966_and_its_relation_to_the_ancestral_Crow_on_the_Northwest_Plains/links/5af5ef330f7e9b026bcedfa2/The-Wold-Bison-Jump-48JO966-and-its-relation-to-the-ancestral-Crow-on-the-Northwest-Plains.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

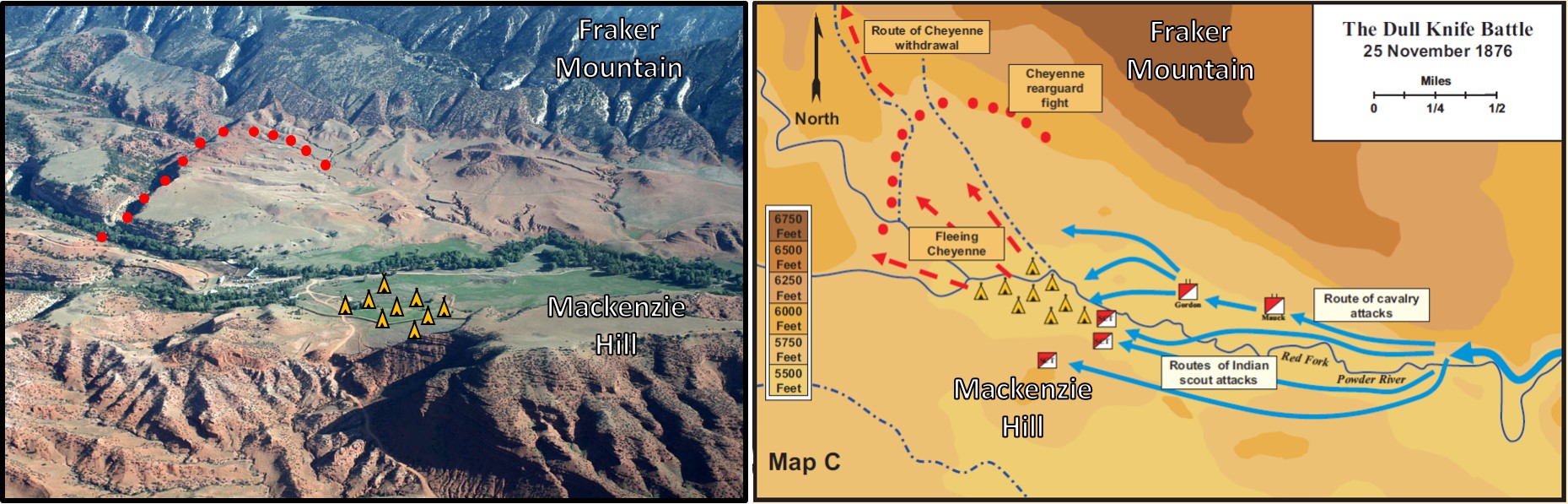

After the U.S. Cavalry’s defeat at the Little Bighorn, Dull Knife’s band of Cheyenne retreated to their remote winter camp along the Red Fork of the Powder River at the north end of the Red Wall. On November 25, 1876, five months after the Little Bighorn battle, a force of 1,000 U.S. Calvary and Indian scouts attacked the sleeping Cheyenne village. The Indians abandoned their tepees, clothing, supplies and established a defensive line across Beartrap Creek and the North Fork of the Red Fork. They escaped the battlefield at nightfall into the frigid minus 30-degree winter night. Within a year, they surrendered, ceded their land and were moved to the Southern Cheyenne reservation in Oklahoma. These were the last free Indians to live in the Red Wall country of Wyoming.

Dull Knife Battlefield at the north end of Red Wall country.

Image: Left: After Rea, T. photo on Robinson, G., 2014,The Dull Knife Fight, 1876: Troops Attack a Cheyenne Village on the Red Fork of Powder River; https://www.wyohistory.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_large/public/dullknifegallery1.jpg?itok=a3z-lv1I;

Right: After: Charles D. Collins Jr., Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 2006; Year: 1854; Source: Charles D. Collins Jr., Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 2006; From collection: Military History Maps, Map 33; https://www.scribd.com/document/101464740/Military-History-Map-of-1854-1890-Atlas-of-the-Sioux-Wars-Part-2

Image: Left: After Rea, T. photo on Robinson, G., 2014,The Dull Knife Fight, 1876: Troops Attack a Cheyenne Village on the Red Fork of Powder River; https://www.wyohistory.org/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_large/public/dullknifegallery1.jpg?itok=a3z-lv1I;

Right: After: Charles D. Collins Jr., Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 2006; Year: 1854; Source: Charles D. Collins Jr., Combat Studies Institute/Combined Arms Research Library, 2006; From collection: Military History Maps, Map 33; https://www.scribd.com/document/101464740/Military-History-Map-of-1854-1890-Atlas-of-the-Sioux-Wars-Part-2

After the removal of Indians in 1876, the big cattle owners moved into the Powder River and Red Wall country in the 1870s. The grasslands treasured by the Indians were now the feeding ground for open range stock. The open range right was enforced by U.S. Marshals, stock detectives and the U.S. Calvary. “Cattle barons” established the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA) in 1872 to organize the industry. They divided the open range into districts, scheduled the annual roundups, managed stock shipment and controlled issuing of cattle brands. The organization became an influential political force and “de facto territorial government.”

Every year the cattle in a district were rounded up. Calves that had been born on the range did not have brands. These cattle and any other unmarked strays were called “mavericks.” Prior to Wyoming’s 1884 Maverick Law, cowboys could go out on the range with their own branding iron and mark cattle. This practice was called “mavericking.” The cattle barons called it “rustling.” The practice infuriated the barons because it cut into their profits. The 1884 law made branding cattle without the approval of the district foreman illegal. Mavericks were now considered the property of the WSGA to be auctioned off to their members only.

The barons sent more and more cattle to the open range. Lush grass lands that thrived with vast herds of migratory bison, who grazed an area briefly then moved on, suffered due to overcrowding with cattle. The severe drought summer of 1886 was followed by the bitterly cold winter of 1886-1887 decimating weakened cattle herds, further reducing profits in the cattle industry.

Every year the cattle in a district were rounded up. Calves that had been born on the range did not have brands. These cattle and any other unmarked strays were called “mavericks.” Prior to Wyoming’s 1884 Maverick Law, cowboys could go out on the range with their own branding iron and mark cattle. This practice was called “mavericking.” The cattle barons called it “rustling.” The practice infuriated the barons because it cut into their profits. The 1884 law made branding cattle without the approval of the district foreman illegal. Mavericks were now considered the property of the WSGA to be auctioned off to their members only.

The barons sent more and more cattle to the open range. Lush grass lands that thrived with vast herds of migratory bison, who grazed an area briefly then moved on, suffered due to overcrowding with cattle. The severe drought summer of 1886 was followed by the bitterly cold winter of 1886-1887 decimating weakened cattle herds, further reducing profits in the cattle industry.

The brutal winter of 1886-1887 decimated the open range cattle, weakened by starvation from the summer’s drought.

Russell, C.M., circa 1900, Waiting for a Chinook; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinook2.gif

Russell, C.M., circa 1900, Waiting for a Chinook; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinook2.gif

The WSGA blamed their problems on rustlers instead of their own mismanagement of range land. Their livelihood was further threatened when homesteaders moved west, fencing the boundaries of their 160-acre plots that the 1862 Homestead Act encouraged them to settle. The powerful cattle barons who ruled the range as their personal fiefdoms were outraged that the settlers used “their” water and “their” grass, blocking "their" cattle from prime grassland and cutting into “their” profits.

Violence between the cattle barons and small leaseholders began along the Sweetwater River near Independence Rock southwest of the Red Wall. Six of the large cattle ranchers lynched suspected rustlers Ellen “Cattle Kate” Watson and James Averill 1889. Later history has shown the couple were innocent of the rustling, they had bought all their cattle legally. Watson and Averell were lynched because they challenged the WSGA.

Throughout this time, the Hole in the Wall outlaws’ sympathies lay with the homesteaders. Some of the citizens even sought refuge with the gangs behind the Red Wall (Erickson, J., 2015, Fly Fishing the Outlaw Trail; http://bigskyjournal.com/fly-fishing-the-outlaw-trail/).

Violence between the cattle barons and small leaseholders began along the Sweetwater River near Independence Rock southwest of the Red Wall. Six of the large cattle ranchers lynched suspected rustlers Ellen “Cattle Kate” Watson and James Averill 1889. Later history has shown the couple were innocent of the rustling, they had bought all their cattle legally. Watson and Averell were lynched because they challenged the WSGA.

Throughout this time, the Hole in the Wall outlaws’ sympathies lay with the homesteaders. Some of the citizens even sought refuge with the gangs behind the Red Wall (Erickson, J., 2015, Fly Fishing the Outlaw Trail; http://bigskyjournal.com/fly-fishing-the-outlaw-trail/).

Ella Watson’s (aka Cattle Kate) cabin on her homestead along Horse Creek (S/2, SE, Section 22, S/2 SE, Section 23, Township 30 North, Range 85 West) in 1912.

Image: Grand Encampment Museum.

Image: Grand Encampment Museum.

After the lynching, Nate Champion of KC Ranch, led a small group of farmers to form the Northern Wyoming Farmers and Stock Growers Association (NWFSGA), threatening the power of the WSGA. The cattle barons ordered their disbandment and blacklisted NWFSGA members from roundups. The NWFSGA responded by announcing their own roundup to take place one month before the WSGA roundup in 1892 with Champion serving as foreman.

The Johnson County War started when the WSGA hired Texas gunmen to kill 70 people suspected of cattle rustling. First on their list was Nate Champion, who they had attempted to assassinate in 1891. On April 9, 1892, 50 men attacked the KC Ranch cabin where he and his partner Ray rented land. Ray was killed early on and Champion fought back alone for five hours, recording his thoughts in a journal. When the assassins set fire to the cabin, Nate grabbed his journal and fled. He was promptly shot down. His last journal entry reads: “Well, they have just got through shelling the house like hail. I heard them splitting wood. I guess they are going to fire the house tonight. I think I will make a break when night comes, if alive. Shooting again. It's not night yet. The house is all fired. Goodbye, boys, if I never see you again.”

Two days later the murderers found themselves pinned down by a sheriff’s posse at the TA Ranch south of Buffalo. The Wyoming Governor and two U.S. senators called for martial law, but President Harrison chose only to send the Calvary to stop the siege. The U.S. 6th Calvary from Fort McKinney arrived, surrounded the ranch and the Johnson County invasion ended. Cattlemen’s violence against “intruders” on the open range continued until the conviction of five of the 1909 Spring Creek raid perpetrators brought peace to the range (see: https://www.geowyo.com/castle-gardens.html).

The Johnson County War started when the WSGA hired Texas gunmen to kill 70 people suspected of cattle rustling. First on their list was Nate Champion, who they had attempted to assassinate in 1891. On April 9, 1892, 50 men attacked the KC Ranch cabin where he and his partner Ray rented land. Ray was killed early on and Champion fought back alone for five hours, recording his thoughts in a journal. When the assassins set fire to the cabin, Nate grabbed his journal and fled. He was promptly shot down. His last journal entry reads: “Well, they have just got through shelling the house like hail. I heard them splitting wood. I guess they are going to fire the house tonight. I think I will make a break when night comes, if alive. Shooting again. It's not night yet. The house is all fired. Goodbye, boys, if I never see you again.”

Two days later the murderers found themselves pinned down by a sheriff’s posse at the TA Ranch south of Buffalo. The Wyoming Governor and two U.S. senators called for martial law, but President Harrison chose only to send the Calvary to stop the siege. The U.S. 6th Calvary from Fort McKinney arrived, surrounded the ranch and the Johnson County invasion ended. Cattlemen’s violence against “intruders” on the open range continued until the conviction of five of the 1909 Spring Creek raid perpetrators brought peace to the range (see: https://www.geowyo.com/castle-gardens.html).

The 6thCalvary deployment to end the siege, April 13, 1892. Location shown on Hole in the Wall-Red Wall aerial image.

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TAranch.jpg

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TAranch.jpg

Nate Champion, hero of the Johnson County War bronze. Statue is in front of the Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum, Buffalo, Wyoming.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

The hero of the Johnson County conflict is Nate Champion. He was added to the Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2014 and a bronze statue stands outside the Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum in Buffalo. The conflict between Wyoming’s large cattle operations and homesteaders, and the outlaws and their canyon hideouts are repeated themes in Western novels and movies. The most famous of the outlaw lairs is probably Wyoming’s Hole in the Wall.

The sheltered isolation that the Indians had in the Red Wall country attracted cowboys whose entrepreneurial and ethical standards differed sharply from the cattle barons and lawful society. The valley and canyons west of the Red Wall provided ample havens for secure hideouts and loot storage. The area was a day’s ride from “civilization.” The Hole in the Wall is one of the mountain passes into this country. It is a 350-foot sandstone escarpment that provided an excellent, easily defended lookout position. The Middle Powder River is the major stream flowing northeastward across the area west of the Red Wall. It has carved a major dip canyon with several caves used by outlaw bands.

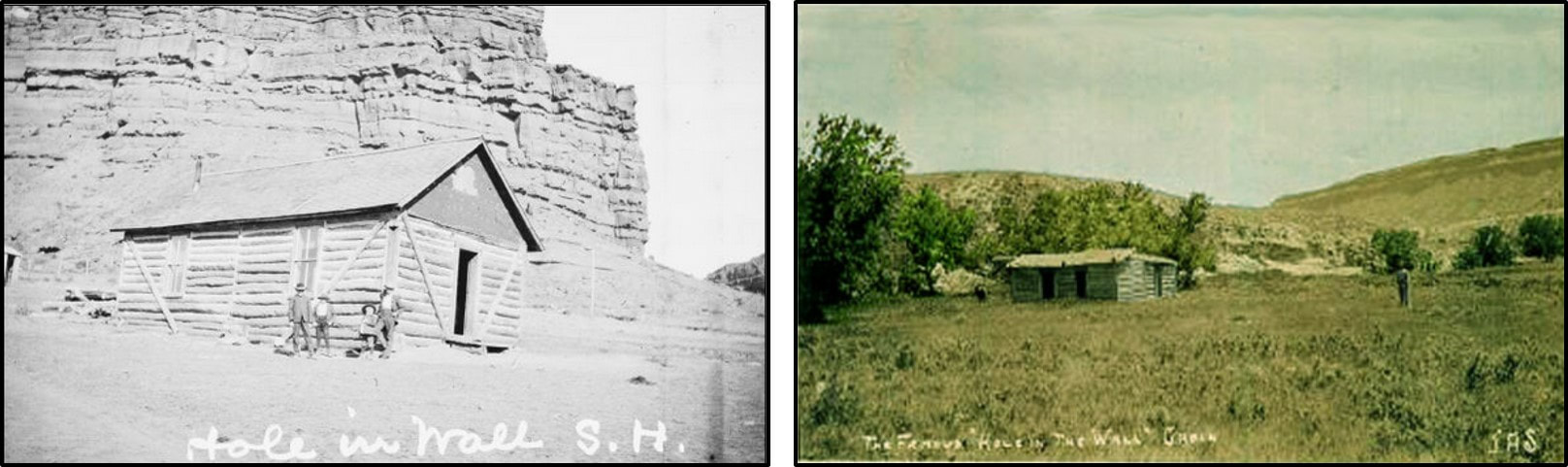

The outlaws were an assortment of cattle rustlers, horse thieves, and train robbers. There were many groups making up the Hole in the Wall “gangs.” Usually 40 outlaws maintained a semi-permanent residence behind the Red Wall. Several cabins provided winter quarters for the gangs. The most famous group of these outlaws was Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch gang. The Hole in the Wall gangs used the location from the end of the Civil War until about 1910 when it and the “Wild West” faded into history.

The sheltered isolation that the Indians had in the Red Wall country attracted cowboys whose entrepreneurial and ethical standards differed sharply from the cattle barons and lawful society. The valley and canyons west of the Red Wall provided ample havens for secure hideouts and loot storage. The area was a day’s ride from “civilization.” The Hole in the Wall is one of the mountain passes into this country. It is a 350-foot sandstone escarpment that provided an excellent, easily defended lookout position. The Middle Powder River is the major stream flowing northeastward across the area west of the Red Wall. It has carved a major dip canyon with several caves used by outlaw bands.

The outlaws were an assortment of cattle rustlers, horse thieves, and train robbers. There were many groups making up the Hole in the Wall “gangs.” Usually 40 outlaws maintained a semi-permanent residence behind the Red Wall. Several cabins provided winter quarters for the gangs. The most famous group of these outlaws was Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch gang. The Hole in the Wall gangs used the location from the end of the Civil War until about 1910 when it and the “Wild West” faded into history.

Two of the cabins at Hole in the Wall. None of these structures remain, but foundations can be seen in a few places. One of the cabins they used is preserved at Old Trail Town in Cody, WY.

Image: Left: Blewer, M., 2013, Wyoming's Outlaw Trail (Images of America), Kindle Edition, Location 364: Right: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/butch.html.

Image: Left: Blewer, M., 2013, Wyoming's Outlaw Trail (Images of America), Kindle Edition, Location 364: Right: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/butch.html.

Hole in the Wall Pass in red sandstone of the Chugwater Group. The boulders were moved by outlaws to hinder passage. Location shown on Hole in the Wall-Red Wall aerial image.

Image: BLM; https://www.wyomingpublicmedia.org/post/hole-wall-40-miles-southwest-kaycee

Image: BLM; https://www.wyomingpublicmedia.org/post/hole-wall-40-miles-southwest-kaycee

Geology of Hole In The Wall & Red Wall Country

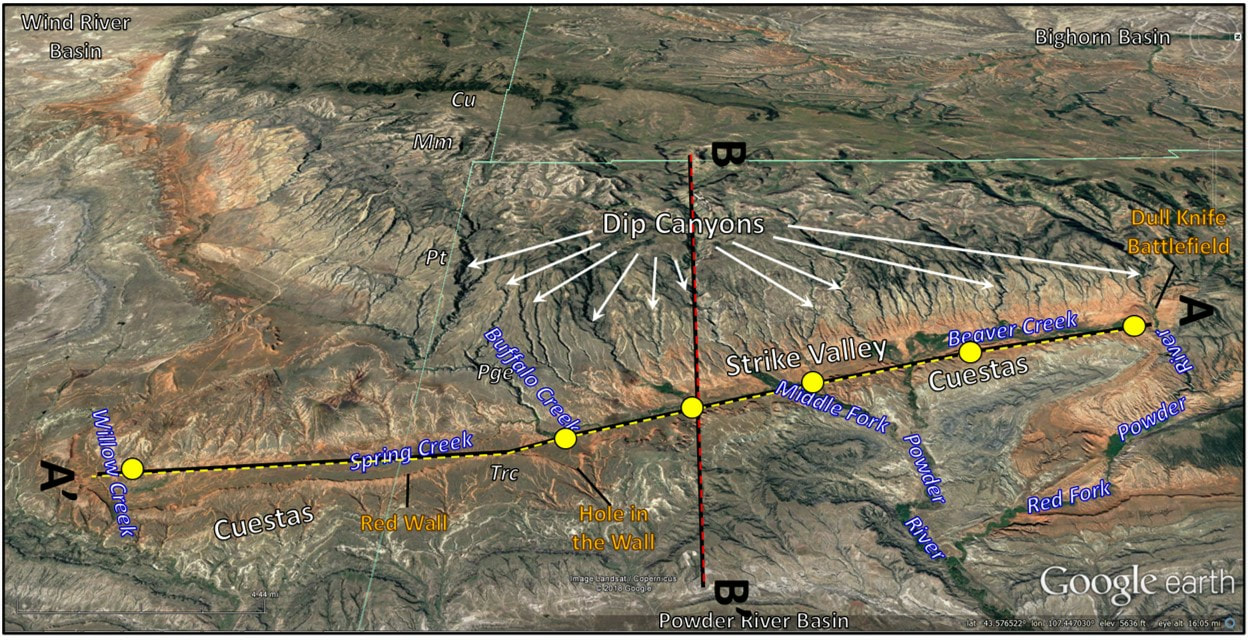

The geology of the Red Wall is like Red Canyon to the southwest in Fremont County, Wyoming (see Red Canyon link, pending). The Red Canyon strike valley extends about 15 miles at the foot of the Wind River Range just southeast of Lander. The Red Wall extends 25 miles along the east flank of the Bighorn Mountains from the Red Fork of the Powder River in the north to Willow Creek at the south end of the range. At Willow Creek, the Chugwater outcrop turns west and follows the south margin of the range for another 25 miles. Red Wall valley is a strike valley developed in basal Mesozoic rock along the back limb of a Laramide Mountain trend. Stratigraphic units to the east of the wall form linear ridges and grassy swales that dip eastward (cuesta landscape). The red color is from iron oxide in the rocks.

Steep dip canyons are carved in Paleozoic rocks along the east flank of the Bighorn Mountains by streams that flow off the uplift. Basement rock are not exposed, but are believed to be Archean (3+ billion year old) granitic gneiss intruded by younger quartz diorite and amphibolite dikes. The area basement rock lies within the Wind River Gneiss Domain (Sims, P.K., Finn, C.A., and Rystrom, V.L., 2001, Preliminary Precambrian basement map showing geologic—geophysical domains, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 01-199, 9 p., revised online, 2009; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2001/ofr-01-0199/downloads/OF01-199.pdf).

Steep dip canyons are carved in Paleozoic rocks along the east flank of the Bighorn Mountains by streams that flow off the uplift. Basement rock are not exposed, but are believed to be Archean (3+ billion year old) granitic gneiss intruded by younger quartz diorite and amphibolite dikes. The area basement rock lies within the Wind River Gneiss Domain (Sims, P.K., Finn, C.A., and Rystrom, V.L., 2001, Preliminary Precambrian basement map showing geologic—geophysical domains, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 01-199, 9 p., revised online, 2009; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2001/ofr-01-0199/downloads/OF01-199.pdf).

Aerial views of Red Wall strike valley above the confluence of the Middle Fork of the Powder River and Beaver Creek. Top: north view showing Castle (north) and Steamboat (south) Rocks on adjacent sides of the river; Bottom: south view showing linear, east dipping ridges (cuestas) formed in the resistant sandstones of the Chugwater. The non-resistant shales and siltstones form the grassy swales between.

Image: Top:Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-In-The-Wall Ranch north aerial image; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ee/Hole-in-the-Wall%2C_Wyoming.jpg; Bottom: Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-In-The-Wall Ranch south aerial image; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hole-in-the-Wall,_Wyoming_-_3.jpg

Image: Top:Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-In-The-Wall Ranch north aerial image; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ee/Hole-in-the-Wall%2C_Wyoming.jpg; Bottom: Beebe, S., 2011, Hole-In-The-Wall Ranch south aerial image; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hole-in-the-Wall,_Wyoming_-_3.jpg

The red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group are 700 to 800 feet thick in the 50-mile long Red Wall area. They consist of fine-grained clastic sediments (sandstones, siltstones and mudstones) deposited in marginal marine to fluvial environments. The Chugwater Group overlies the Triassic-Permian Goose Egg Formation, which forms the valley floor, and is overlain by the Jurassic Sundance Formation. The Chugwater red beds are the most easily recognized rocks in the geologic landscape of Wyoming.

The Chugwater Group is made up of three formations and one unnamed unit. The oldest and thickest unit is the Red Peak Formation (Trcrp). The lithology of this unit is very fine silt to mud-dominated beds with two laterally continuous sheet sandstones from a delta-front depositional environment. Scattered channels and scour surfaces suggest the presence of a partial braided stream system. The Alcova Limestone (Trca) is a thin carbonate unit that represents an eastward marine flooding event called a transgression. The Crow Mountain Sandstone (Trcm) is a fine-grained unit forming the upper portion of the plateaus and buttes of the Red Wall. The sand is a return of clastic sediments after the Alcova Seaway receded and represents tidal flat and nearshore coastal settings. Overlaying the Crow Mountain is an unnamed sequence of red beds (Trcurb) that were deposited in a fluvial-deltaic plain. The uppermost units represent lake deposits. The upper units are less resistant to erosion than the older portions of the Chugwater and form a grassy plain on the plateau extending to the Sundance Formation ridgeline. The Popo Agie Formation is not present in the area due to either non-deposition or erosion.

The Chugwater Group is made up of three formations and one unnamed unit. The oldest and thickest unit is the Red Peak Formation (Trcrp). The lithology of this unit is very fine silt to mud-dominated beds with two laterally continuous sheet sandstones from a delta-front depositional environment. Scattered channels and scour surfaces suggest the presence of a partial braided stream system. The Alcova Limestone (Trca) is a thin carbonate unit that represents an eastward marine flooding event called a transgression. The Crow Mountain Sandstone (Trcm) is a fine-grained unit forming the upper portion of the plateaus and buttes of the Red Wall. The sand is a return of clastic sediments after the Alcova Seaway receded and represents tidal flat and nearshore coastal settings. Overlaying the Crow Mountain is an unnamed sequence of red beds (Trcurb) that were deposited in a fluvial-deltaic plain. The uppermost units represent lake deposits. The upper units are less resistant to erosion than the older portions of the Chugwater and form a grassy plain on the plateau extending to the Sundance Formation ridgeline. The Popo Agie Formation is not present in the area due to either non-deposition or erosion.

Red Wall area Chugwater Group outcrop. The Popo Agie Formation is not present here. Solid white lines are formation contacts, dashed are intraformational subdivisions shown on stratigraphic column. Abbreviation: Ju, Jurassic strata undivided.

Image: Stratigraphic column: After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 10, p. E15; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf;Outcrop: After Bodin, N., 2015, A Tour to Hole in the Wall: Writing Wranglers and Warriors; https://writingwranglersandwarriors.wordpress.com/2015/01/24/a-tour-to-hole-in-the-wall/amp/

Image: Stratigraphic column: After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 10, p. E15; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf;Outcrop: After Bodin, N., 2015, A Tour to Hole in the Wall: Writing Wranglers and Warriors; https://writingwranglersandwarriors.wordpress.com/2015/01/24/a-tour-to-hole-in-the-wall/amp/

Stratigraphic cross section along the Red Wall valley. The datum is the base of the Alcova Limestone. Location shown on geologic maps.

Image: After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 5, p. E7; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf.

Image: After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 5, p. E7; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf.

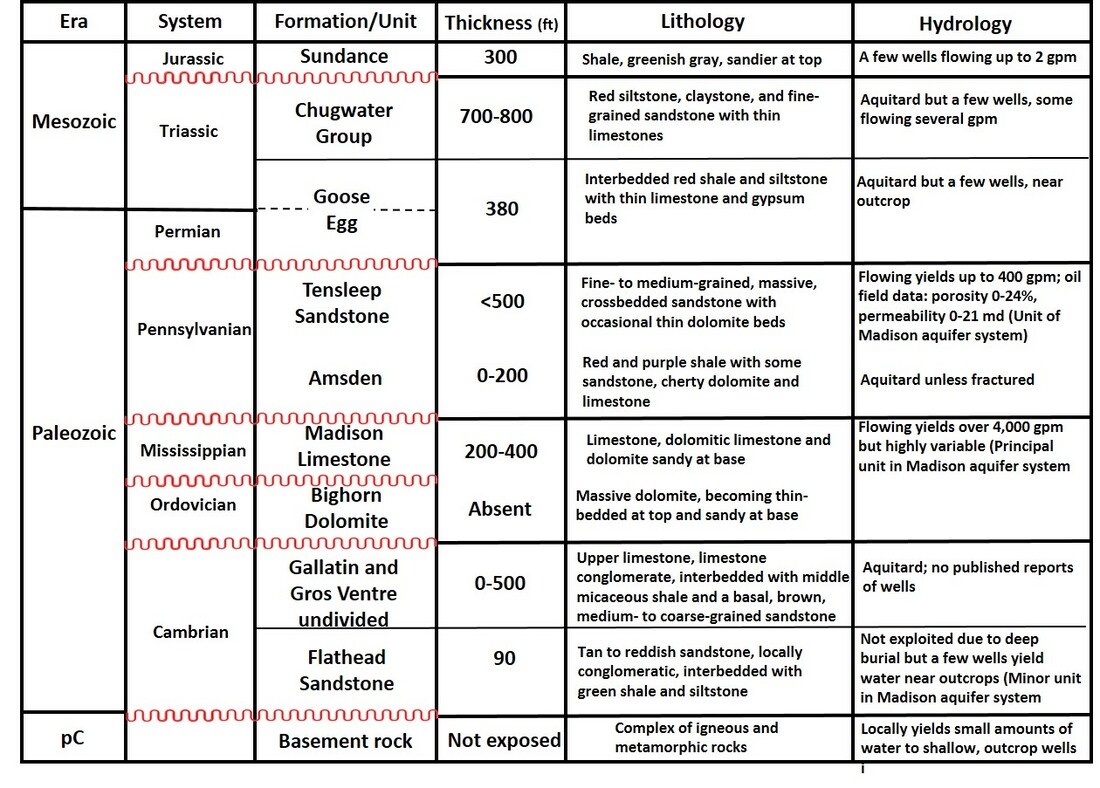

Lithologic and hydrologic characteristics of bedrock exposed on the western flank of the Powder River structural basin. Unconformities (surfaces of erosion) shown by red wavy lines.

Image: After HKM Engineering Inc., Lord Consulting, and Watts and Associates, 2002, Table 1, p. 23-24, Available Ground Water Determination Technical Memoranda, Technical Memoranda, Powder/Tongue River Basin Plan Final Report;http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/powder/2002/techmemos/gwdeterm/gwdeterm_appb.pdf.

Image: After HKM Engineering Inc., Lord Consulting, and Watts and Associates, 2002, Table 1, p. 23-24, Available Ground Water Determination Technical Memoranda, Technical Memoranda, Powder/Tongue River Basin Plan Final Report;http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/powder/2002/techmemos/gwdeterm/gwdeterm_appb.pdf.

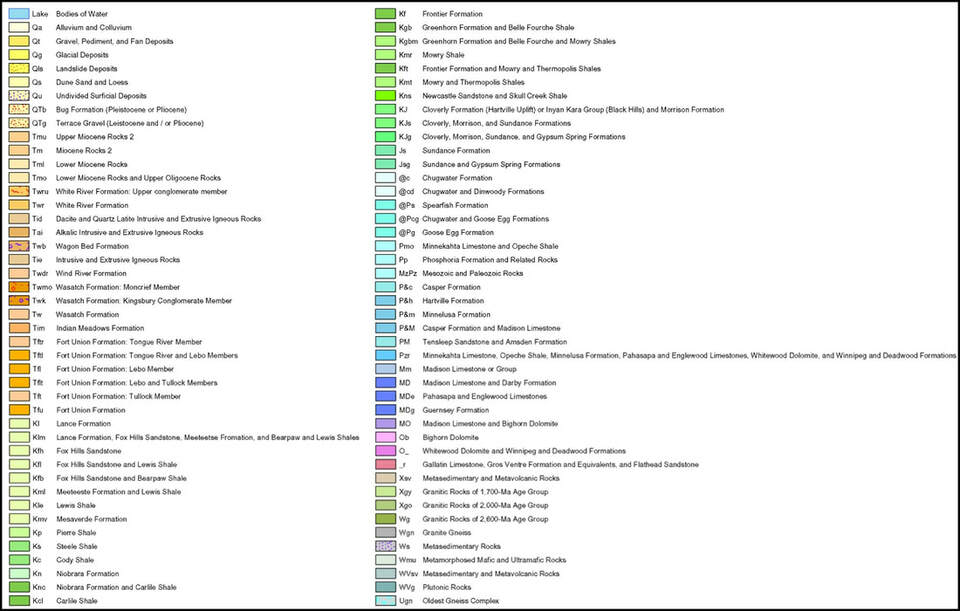

The geologic map of the Powder River watershed shows the pinch out of Ordovician rocks (O) between the Red Fork and Beaver Creek. The Devonian rocks (D) southern depositional limit was between the North Fork and Red Fork of the Powder River. South of Beaver Creek Mississippian rocks lie unconformably on Cambrian rocks in the Red Wall area. Southernmost outcrop of Precambrian genesis complex is shown at The Horn. Location of cross sections AA’ (yellow dashed line) and BB’ (red dashed line) shown.

Image: After HKM Engineering Inc., Lord Consulting, and Watts and Associates, 2002, Appendix B: Geology and Ground Water Use Plates, Plate B2 & B2.1, p. 50-51, Technical Memoranda, Powder/Tongue River Basin Plan Final Report;http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/powder/2002/techmemos/gwdeterm/gwdeterm_appb.pdf.

Image: After HKM Engineering Inc., Lord Consulting, and Watts and Associates, 2002, Appendix B: Geology and Ground Water Use Plates, Plate B2 & B2.1, p. 50-51, Technical Memoranda, Powder/Tongue River Basin Plan Final Report;http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/powder/2002/techmemos/gwdeterm/gwdeterm_appb.pdf.

West aerial view of Hole in the Wall-Red Wall country showing erosional features and drainages developed on the Laramide Bighorn uplift.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Generalized structural cross section BB’ of the Bighorn Mountains southeastern dip slope. Location shown on geologic maps and image above. Abbreviations: Ku, Cretaceous undifferentiated, Ju, Jurassic undifferentiated, Trc, Triassic Chugwater Group, Pge, Permian Goose Egg, Pt, Pennsylvanian Tensleep, Pa, Pennsylvanian Amsden, Mm, Mississippian Madison, Cu, Cambrian undifferentiated, pC, Precambrian basement rock.

Image: Steele, K. 2019, After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 4, p. E4; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf.

Image: Steele, K. 2019, After Cavaroc, V.V. and Flores, R.M., 1991, Red beds of the Triassic Chugwater Group, southwestern Powder River basin, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1917- E, Fig. 4, p. E4; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1917e/report.pdf.

The dip canyons are steep V-shaped erosional features with 1,000 to 1,400 feet of relief. The Paleozoic section is exposed on the canyon walls. The Devonian and Ordovician rocks pinch out to the south. The Mississippian Madison Formation lies directly on Cambrian rocks just north of Blue Creek west of Barnum. Precambrian rocks are not exposed, but underlie the Cambrian Flathead Formation. Numerous caves are developed within the Paleozoic carbonate rocks. At least two of the caves were used by the outlaws in Hole in the Wall area. Soldiers posted at Fort Houck stage station left their names and dates of service in caves developed along Buffalo Creek Canyon (http://www.outlawtrails.com/rides/north-american-rides/hole-in-the-wall/).

Outlaw Cave #1. Cave is in Madison Limestone at the bottom of a half mile trail that drops 500 feet into the Middle Fork Powder River.

Image: Mark Fisher

Image: Mark Fisher

Outlaw Cave #2. Cave is in Madison Limestone on the south canyon wall in the Middle Fork of the Powder River dip canyon.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

The south slopes (north-facing) of these canyons have a ponderosa pine dominated tree canopy with some Douglas fir and limber pine. The north-facing slopes receive more winter snow due to being in shadow. This provides the extra moisture the trees require. A few cottonwoods grow at the bottom of the canyons near the streams. The opposite slopes are preferentially covered with shrubs and grasses. The two major outcrop benches exposed in the canyons are the Pennsylvanian Tensleep Sandstone (upper) and the Mississippian Limestone (lower). These rock units are also major reservoirs in the subsurface for hydrocarbons (Phosphoria petroleum system) and ground water (Madison aquifer system). The poorly exposed Paleozoic shaley rocks of the canyons generally serve as seals or barriers to fluid movement in the subsurface (see lithologic and hydrologic characteristics table above).

West aerial view of several dip canyons showing variation in slope habitat. Tree canopy favors the more watered north-facing south slopes (left) while shrubs and grasses dominate the south-facing slopes (right).

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Geologic processes acting over deep time created the Red Wall and the Wyoming landscape. Major conflicts in the Red Wall region were generally about control of land and its resources. This was true of the inter-tribal battles, the wars between native people and the United States, the cattle barons dispute with the homesteaders, and the outlaws of Hole in the Wall gangs against 19th century society. The rusty red escarpments of Triassic Chugwater Formation provided a dramatic backdrop for these stories of the Wild West.

Charles Keiser’ short HD video of the Red Wall: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjJskJ5XW60.

Middle Fork of the Powder River and Outlaw Cave campground video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KYEUkcWi-mw.

Fade to the music of Elmer Bernstein’s theme from the Magnificent Seven with cowboy and horse atop the Red Wall… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45KAjt7v4t4).

Charles Keiser’ short HD video of the Red Wall: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjJskJ5XW60.

Middle Fork of the Powder River and Outlaw Cave campground video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KYEUkcWi-mw.

Fade to the music of Elmer Bernstein’s theme from the Magnificent Seven with cowboy and horse atop the Red Wall… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=45KAjt7v4t4).

Things to Do

Canyon Middle Fork of Powder River at Outlaw Cave Campground. Upper cliffs are Tensleep Sandstone, covered slope is Amsden Formation and inner canyon is upper part of Madison Limestone.

Image: Mark Fisher

Image: Mark Fisher

Our two recommendations are drives/hikes to Outlaw Cave in the Middle Fork of the Powder River and to the Hole in the Wall. Best time of year to visit is during May and June when the green vegetation contrasts with the red Chugwater. Because of the lack of public road connecting the two places, it is difficult to do both of these easily in one day, even though they are not that far apart. A 4WD high clearance vehicle trip to the Hole in the Wall takes you past some beautiful Chugwater outcrops. It is a long drive on isolated dirt roads with minimal cell phone reception. A BLM map for Midwest and Kaycee would be helpful. Don't travel these roads if they are wet. The actual "Hole in the Wall" is a gap in the cliffs, not a spectacular hole or cave (lower your expectations).

The drive and hike to Outlaw Cave takes you to a pretty canyon of the Middle Fork of the Powder River. Trail starts in Outlaw Cave Campground near the toilet and heads down a ravine through Tensleep Sandstone outcrops. It is a steep and rocky trail with about 500 feet of vertical elevation change over about 1/2 mile each way. A walking stick would be helpful because of loose rocks and steepness. Outlaw Cave is across the river (no bridge) on the west wall in the Madison just downstream about 50 yards from a rock window. Outlaw Cave 2 is on the same side of the river as the Outlaw Cave Trail (east wall), but is further downstream about 0.2 mile on a sketchy trail overhanging the river. You must decide for yourself if accessing these caves is safe.

The following BLM webpages give directions and tips on road & trail conditions to access these places:

Outlaw Cave

Hole in the Wall

The drive and hike to Outlaw Cave takes you to a pretty canyon of the Middle Fork of the Powder River. Trail starts in Outlaw Cave Campground near the toilet and heads down a ravine through Tensleep Sandstone outcrops. It is a steep and rocky trail with about 500 feet of vertical elevation change over about 1/2 mile each way. A walking stick would be helpful because of loose rocks and steepness. Outlaw Cave is across the river (no bridge) on the west wall in the Madison just downstream about 50 yards from a rock window. Outlaw Cave 2 is on the same side of the river as the Outlaw Cave Trail (east wall), but is further downstream about 0.2 mile on a sketchy trail overhanging the river. You must decide for yourself if accessing these caves is safe.

The following BLM webpages give directions and tips on road & trail conditions to access these places:

Outlaw Cave

Hole in the Wall

The material on this page is copyrighted