North view from Iceberg Peak of Grasshopper Lakes and Grasshopper Glacier, Beartooth Mtns.

Photo by Mark Fisher, 2015

Photo by Mark Fisher, 2015

Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (2 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Extinct locusts (Melanoplus spretus) entombed within glacial ice preserved at cirques high in the Rocky Mountains of Montana and Wyoming.

History of Grasshopper Glaciers

The first report of Grasshopper Glacier or the existence of any glaciers in the Snowy Range (now the Beartooth Mountains) is in James P. Kimball’s report of his 1898 survey.

“A really astonishing feature of the glacier is the one which naturally has given name to it, as known to prospectors from Cooke. Myriads of grasshoppers, in periodic southward flight from the prairie, have succumbed to the rigor of cold and wind, to be engulfed in the snow and finally entombed in the ice. Thousands of tons of grasshopper remains are the principal morainal material fringing the lower edge, washed out in furrows wherever by action of the sun the surface has been grooved into runlets of descending water. No fragment of ice can be broken so small as not to contain grasshopper remains, melting and regelation having torn all but a small proportion of the fallen insects into a coarse powder, only the more enduring parts having resisted reduction. Grasshoppers that gained the west side of the pass seem to have been laid low before further descent, all congealed patches of snow in the pass likewise being charged in the same way (Kimball, 1899, p. 207).”

There are three other glaciers bearing the Grasshopper name located in the Beartooth and Crazy Mountains of Montana, and in the Wind River Range of Wyoming. Several other named ice fields in these same mountain highlands also were reported to contain frozen Acrididae. None were as well preserved as those found on Knife Point Glacier, Wind River Mountains.

“A really astonishing feature of the glacier is the one which naturally has given name to it, as known to prospectors from Cooke. Myriads of grasshoppers, in periodic southward flight from the prairie, have succumbed to the rigor of cold and wind, to be engulfed in the snow and finally entombed in the ice. Thousands of tons of grasshopper remains are the principal morainal material fringing the lower edge, washed out in furrows wherever by action of the sun the surface has been grooved into runlets of descending water. No fragment of ice can be broken so small as not to contain grasshopper remains, melting and regelation having torn all but a small proportion of the fallen insects into a coarse powder, only the more enduring parts having resisted reduction. Grasshoppers that gained the west side of the pass seem to have been laid low before further descent, all congealed patches of snow in the pass likewise being charged in the same way (Kimball, 1899, p. 207).”

There are three other glaciers bearing the Grasshopper name located in the Beartooth and Crazy Mountains of Montana, and in the Wind River Range of Wyoming. Several other named ice fields in these same mountain highlands also were reported to contain frozen Acrididae. None were as well preserved as those found on Knife Point Glacier, Wind River Mountains.

Glaciers reported to have “grasshoppers” entombed in the ice.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

The most famous “Grasshopper Glacier” is ten miles north of Cooke City in the Beartooth Mountains. It was a former tourist attraction reached by foot, horse or jeep (prior to the formation of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness in 1978). It contained the extinct Rocky Mountain locust that used to swarm over the Great Plains devouring crops.

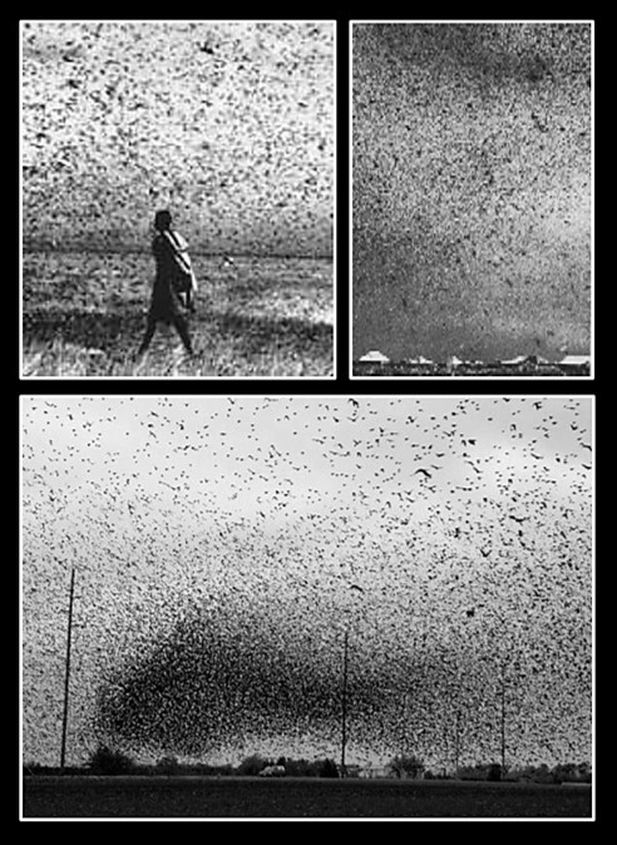

The Rocky Mountain locust, Melanoplus spretus, was a scourge to Great Plains agriculture in the 1860s and 1870s. The word locust is from Latin, locus ustus, meaning “burnt place” (alluding to the devastation of the swarm). The species name spretus is Latin meaning “despised.” High concentration of the species would metamorphose and move out from breeding grounds in river plains of the Northern Rockies and Canada every six to ten years. The migrations would repeat for a few years, then they would pause for several years.

The Rocky Mountain locust, Melanoplus spretus, was a scourge to Great Plains agriculture in the 1860s and 1870s. The word locust is from Latin, locus ustus, meaning “burnt place” (alluding to the devastation of the swarm). The species name spretus is Latin meaning “despised.” High concentration of the species would metamorphose and move out from breeding grounds in river plains of the Northern Rockies and Canada every six to ten years. The migrations would repeat for a few years, then they would pause for several years.

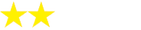

Images of 1875 Rocky Mountain Locust swarm.

Image: http://www.thorntonweather.com/blog/local-news/dnc-weather-denver-weather-history-for-august-25-28/attachment/grasshopper/, and http://www.kosuyolucilingir.info/cave/lod/locust-swarm-1875.shtml.

Image: http://www.thorntonweather.com/blog/local-news/dnc-weather-denver-weather-history-for-august-25-28/attachment/grasshopper/, and http://www.kosuyolucilingir.info/cave/lod/locust-swarm-1875.shtml.

The locusts bred on the river margins and banks in the Rocky Mountains. Locusts have two behavioral phases, normal solitary and migratory. They act like regular grasshoppers in the normal behavior mode, but in drought years their populations congregate, leading to swarming. Crowding increases their serotonin causing their bodies to darken, their wings to grow longer, and increasing their appetites to rapacious. They migrated west and east from the Rockies devouring almost everything in their path. Farmers quipped they “ate everything but the mortgage.” Thousands of locusts became trapped in alpine glacial ice during the migration. Some of the locusts became entombed in the ice by blizzards or winds that blew them onto the ice where they froze. The different grasshopper layers found within the glaciers marked seasonal swarms. It is probable that the locusts were trapped on several more glaciers than are currently recognized but they have vanished due to the rapid retreat of glaciers in the Rockies.

Melanoplus spretus breeding grounds.

Image: After https://entomologytoday.org/rocky-mountain-locust-historic-range-map/ .

Image: After https://entomologytoday.org/rocky-mountain-locust-historic-range-map/ .

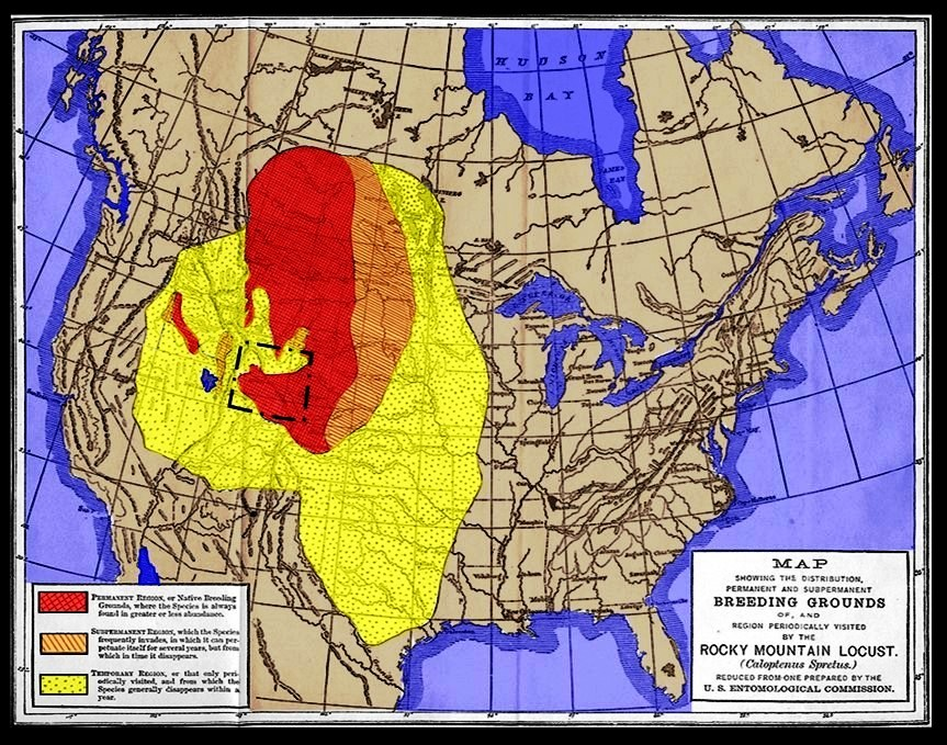

The 1875 Albert’s Swarm holds the place in the Guinness Book of World Records as “the greatest concentration of animals ever.” It was named after Albert Child who collected data on the swarm by telegraphing neighboring towns for information, then estimated its size. One of the great mysteries of the locusts is that after the 1875 swarm they largely disappear. They became extinct within three decades of Albert’s Swarm. The last live specimens were observed in Canada in 1902.

Rocky Mountain Locust, Melanoplus spretus, swarm infestations 1855 to 1875. In 1875, Doctor Albert L. Child of the U.S. Signal Corps watched a mile-high swarm of locusts pass overhead in Plattsmouth, Nebraska, for five days straight. Together with telegraph reports from neighboring towns, Child estimated the swarm to be 110 miles wide and 1,800 miles long (198,000 square miles). “Albert’s Swarm” was the largest such assembly of organisms in recorded history, estimated at 12.5 trillion locusts.

Image: Base Map: https://www.worldmapsonline.com/np_geo/us_physical_cont.htm; Data from After Grice, G. and Murawski, D.A., 2003, Hunger on the Wing: Discover Magazine; http://discovermagazine.com/2003/jul/featwing.

Image: Base Map: https://www.worldmapsonline.com/np_geo/us_physical_cont.htm; Data from After Grice, G. and Murawski, D.A., 2003, Hunger on the Wing: Discover Magazine; http://discovermagazine.com/2003/jul/featwing.

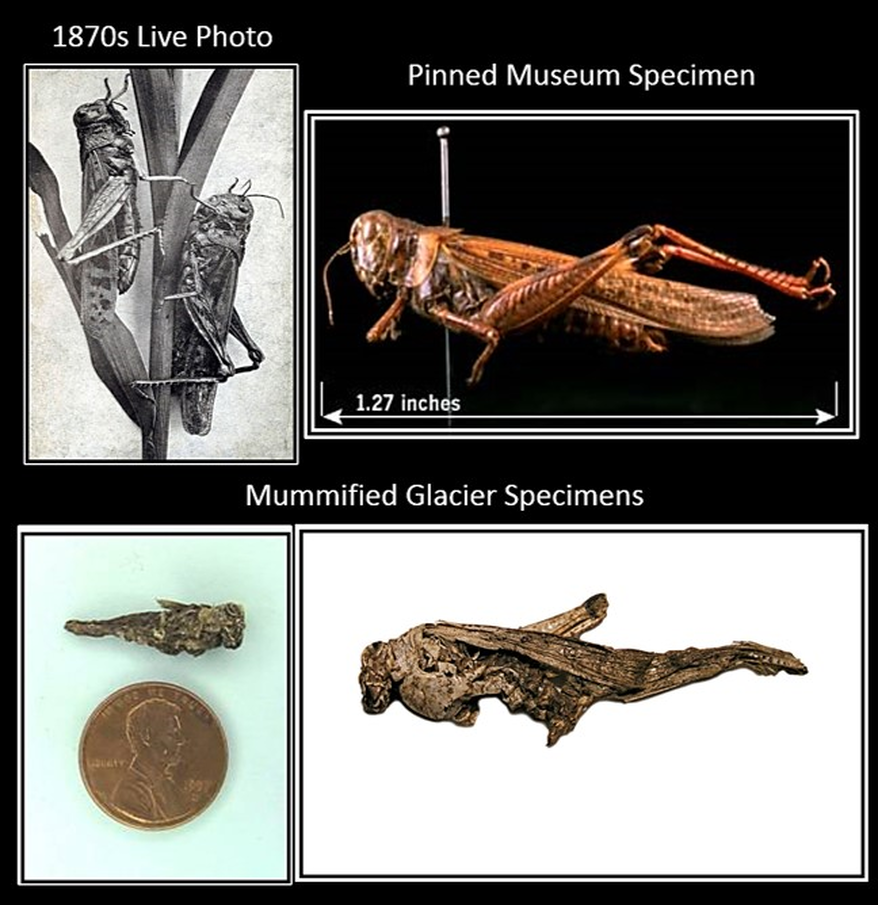

Live locusts: Wikipedia, 1870s, Rocky Mountain locust, Melanoplus spretus: Jackoby’s Art Gallery; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rocky_Mountain_locust#/media/File:Minnesota_locusts.jpg;

Pinned specimen: Grice, G. and Murawski, D.A., 2003, Hunger on the Wing: Discover Magazine; http://discovermagazine.com/2003/jul/featwingfeatwing;

Specimen with penny: Bowell, K., 2010, The Rocky Mountain Locust: The Fort Collins Museum & Discovery Science Center Blog; https://fcmdsc.wordpress.com/2010/09/17/the-rocky-mountain-locust/ Large Specimen: Serlin, D. and Lockwood, J., 2007, Days of the Locust: An Interview with Jeffrey Lockwood: Cabinet Magazine Issue 25; http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/25/serlin.php.

Pinned specimen: Grice, G. and Murawski, D.A., 2003, Hunger on the Wing: Discover Magazine; http://discovermagazine.com/2003/jul/featwingfeatwing;

Specimen with penny: Bowell, K., 2010, The Rocky Mountain Locust: The Fort Collins Museum & Discovery Science Center Blog; https://fcmdsc.wordpress.com/2010/09/17/the-rocky-mountain-locust/ Large Specimen: Serlin, D. and Lockwood, J., 2007, Days of the Locust: An Interview with Jeffrey Lockwood: Cabinet Magazine Issue 25; http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/25/serlin.php.

The swarms that plagued the Great Plains in the second half of the nineteenth century not only devastated agricultural crops, but also devoured rope, clothes, curtains, wool off sheep and each other. The hordes could blot out the sun for up to six hours. Fire, poison, brooms, farm tools, shotguns, all sorts of jerry-rigged crushers and vacuum devices, and prayers were used to repel and destroy the locusts to little effect.

Nebraska had a Grasshopper Law that required all able-bodied men, 16 to 60, to work at least two days to eliminate locusts at hatching time. Several states had bounty offers per bushel of locusts. Recipes for locust delicacies began to appear. Culinary wags claimed that locust tasted just like crawfish or could make an excellent fricassee.

Nebraska had a Grasshopper Law that required all able-bodied men, 16 to 60, to work at least two days to eliminate locusts at hatching time. Several states had bounty offers per bushel of locusts. Recipes for locust delicacies began to appear. Culinary wags claimed that locust tasted just like crawfish or could make an excellent fricassee.

Rocky Mountain locust outbreaks were cyclical and driven by drought. They came to be called “locust weather” and shops had “locust sales.” But then the swarms began to lessen. Then the ravaging bugs disappeared. The Rocky Mountain Locust mysteriously went extinct.

Several theories were posited for the extinction of the Rocky Mountain Locust. These ranged from the planting of alfalfa, vegetation changes due to the demise of bison, some unknown man-made interference, climate change from the Little Ice Age and fire. Dr. Jeffrey Lockwood, University of Wyoming entomologist, began investigating the locust extinction in 1987. He reviewed historic records and explored the grasshopper glaciers. His synthesis of historic and new data can be described as the “cows and plows” theory. He proposed that that the conversion of primary locust breeding grounds at the Three Forks of the Missouri in Montana and the Yellowstone Valley of Wyoming and Montana to agriculture and livestock-raising during the 1880s was the cause of their disappearance.

The population in the Rocky Mountain west increased by nearly two million people in the 1870s and the number of farms doubled between 1870 and 1890. The settlers cultivated the land that was the permanent breeding grounds for the locusts. Tilling of the soil where the locust eggs were laid had been shown to prevent hatching. The scale of settling and farming of this land in the three decades from the 1870s was more than in the previous 250 years; and it occurred when the locusts were recovering from the last swarm.

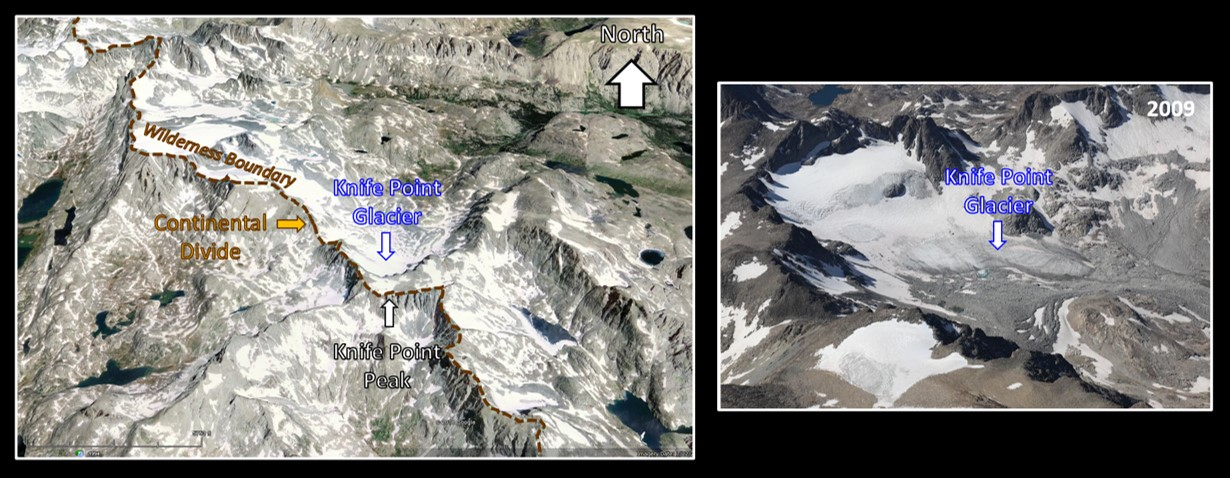

Lockwood’s team sought to recover specimens of Rocky Mountain Locust before they were lost forever due to glacier melting. They spent several years exploring the “Grasshopper Glaciers” of the region but found only locust fragments or the remains of modern grasshoppers. In 1994 they heard about remains present on Knife Point Glacier in the Wind River Mountains. Preserved body remains of the extinct locusts were discovered 8 to 10 inches within the ice. Radiocarbon dating of specimens collected revealed that the locusts were trapped near the end of the Middle Ages.

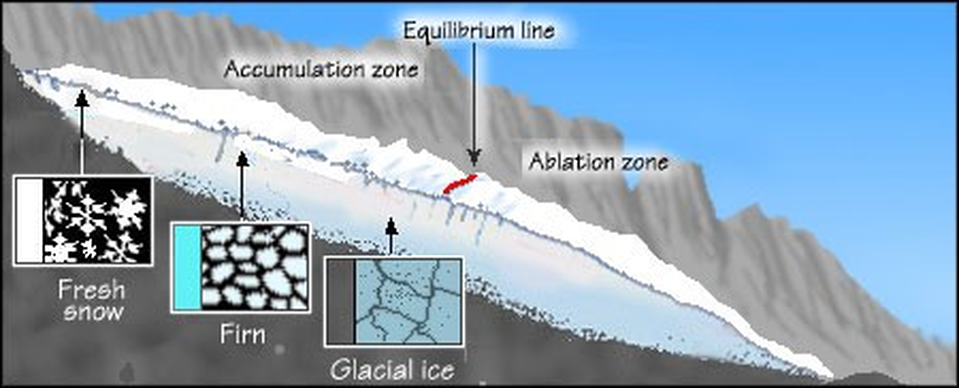

Glaciers are ice features that form from snow that lasts beyond the summer thaw. Over time the snow recrystallizes into dense glacial ice in the zone of accumulation. Glaciers move from the weight of the overlying ice which causes it to deform and flow. The meltwater at the base provides lubrication. The combination of climate, surface slope, gravity and pressure are factors in their motion. Glaciers are composed of ice, snow, water, rocks and sediment. When a glacier melts (ablates) it drops its carried load as moraines and erratics. The entrained rocks help erode, scratch and mold the landscape beneath the ice. Currently glaciers cover only ten percent of the land area on Earth, but they hold 69 percent of the world’s fresh water. Since the early twentieth century, the world’s glaciers have been rapidly receding.

Several theories were posited for the extinction of the Rocky Mountain Locust. These ranged from the planting of alfalfa, vegetation changes due to the demise of bison, some unknown man-made interference, climate change from the Little Ice Age and fire. Dr. Jeffrey Lockwood, University of Wyoming entomologist, began investigating the locust extinction in 1987. He reviewed historic records and explored the grasshopper glaciers. His synthesis of historic and new data can be described as the “cows and plows” theory. He proposed that that the conversion of primary locust breeding grounds at the Three Forks of the Missouri in Montana and the Yellowstone Valley of Wyoming and Montana to agriculture and livestock-raising during the 1880s was the cause of their disappearance.

The population in the Rocky Mountain west increased by nearly two million people in the 1870s and the number of farms doubled between 1870 and 1890. The settlers cultivated the land that was the permanent breeding grounds for the locusts. Tilling of the soil where the locust eggs were laid had been shown to prevent hatching. The scale of settling and farming of this land in the three decades from the 1870s was more than in the previous 250 years; and it occurred when the locusts were recovering from the last swarm.

Lockwood’s team sought to recover specimens of Rocky Mountain Locust before they were lost forever due to glacier melting. They spent several years exploring the “Grasshopper Glaciers” of the region but found only locust fragments or the remains of modern grasshoppers. In 1994 they heard about remains present on Knife Point Glacier in the Wind River Mountains. Preserved body remains of the extinct locusts were discovered 8 to 10 inches within the ice. Radiocarbon dating of specimens collected revealed that the locusts were trapped near the end of the Middle Ages.

Glaciers are ice features that form from snow that lasts beyond the summer thaw. Over time the snow recrystallizes into dense glacial ice in the zone of accumulation. Glaciers move from the weight of the overlying ice which causes it to deform and flow. The meltwater at the base provides lubrication. The combination of climate, surface slope, gravity and pressure are factors in their motion. Glaciers are composed of ice, snow, water, rocks and sediment. When a glacier melts (ablates) it drops its carried load as moraines and erratics. The entrained rocks help erode, scratch and mold the landscape beneath the ice. Currently glaciers cover only ten percent of the land area on Earth, but they hold 69 percent of the world’s fresh water. Since the early twentieth century, the world’s glaciers have been rapidly receding.

Ice and snow layers in the ablation and accumulation zones during late summer.

Image: Granshaw, F.D. and Fountain, A.G., 2002, Questions about Glaciers, Climate and Streamflow: What is a glacier?: Portland State University; http://www.glaciers.pdx.edu/Projects/LearnAboutGlaciers/Skagit/Basics00.html.

Image: Granshaw, F.D. and Fountain, A.G., 2002, Questions about Glaciers, Climate and Streamflow: What is a glacier?: Portland State University; http://www.glaciers.pdx.edu/Projects/LearnAboutGlaciers/Skagit/Basics00.html.

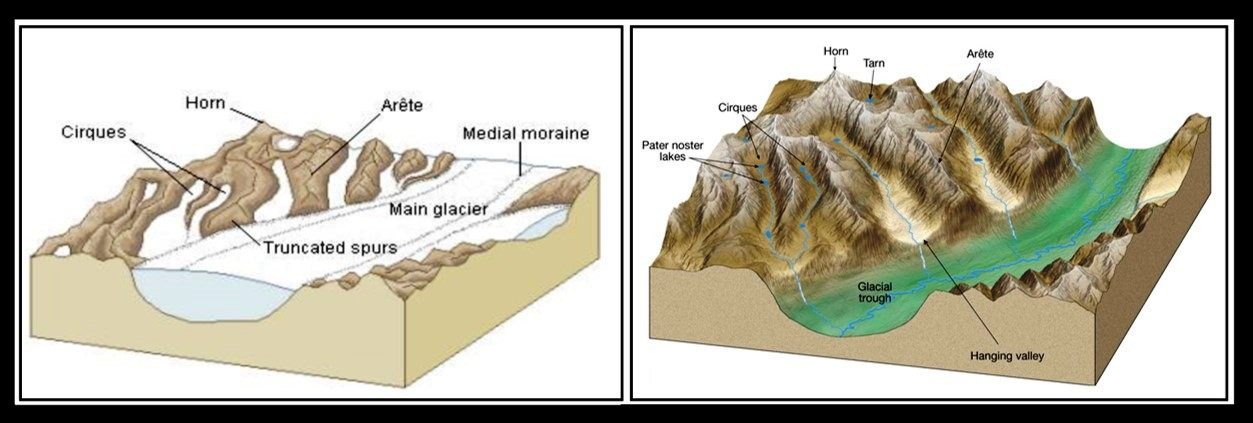

Glacial formed features during and post-ice presence.

Image: Left: https://people.uwec.edu/jolhm/Superior2007/TeamC/landforms.html;

Right: http://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/637/flashcards/268637/png/screen-capture-11337663412142.png.

Image: Left: https://people.uwec.edu/jolhm/Superior2007/TeamC/landforms.html;

Right: http://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/637/flashcards/268637/png/screen-capture-11337663412142.png.

The Alpine glaciers of the Rockies are thought to be remnants from the Little Ice Age (1300 to 1870). The Wind River Range holds the largest concentration of these glaciers in the Rocky Mountains. A 2014 report concluded that total glacier volume in the Wind River Range had decreased by 63 percent since 1966. The alarming rate of ice loss has allowed the frozen insect remains to decompose and be lost at all the reported grasshopper glaciers in the region.

The remaining Alpine glaciers cling to northern and eastern slopes, high on the mountains of the Rockies. They are all disappearing at an alarming rate. Glacier National Park in northern Montana, probably the best studied glacial region, may have no glaciers by the middle of this century. The grasshoppers entombed within any glacier will most likely disappear before all the ice is gone.

The remaining Alpine glaciers cling to northern and eastern slopes, high on the mountains of the Rockies. They are all disappearing at an alarming rate. Glacier National Park in northern Montana, probably the best studied glacial region, may have no glaciers by the middle of this century. The grasshoppers entombed within any glacier will most likely disappear before all the ice is gone.

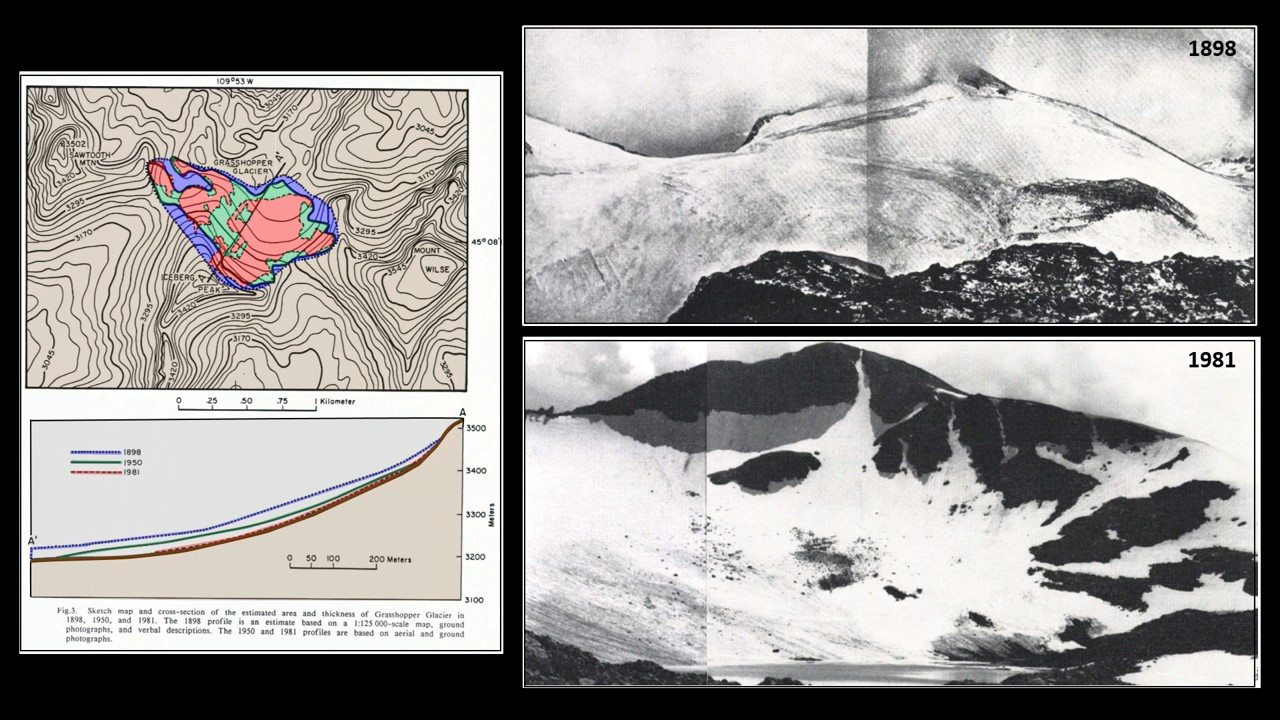

Grasshopper Glacier north of Cooke City, Beartooth Mountains, Montana.

Image: After Ferrigno, J.G., 1986, Recession of Grasshopper Glacier since 1898:Annals of Glaciology, Figs. 1, 2 & 3, p. 66 & 67; https://www.igsoc.org/annals/8/igs_annals_vol08_year1985_pg65-68.pdf.

Image: After Ferrigno, J.G., 1986, Recession of Grasshopper Glacier since 1898:Annals of Glaciology, Figs. 1, 2 & 3, p. 66 & 67; https://www.igsoc.org/annals/8/igs_annals_vol08_year1985_pg65-68.pdf.

Grasshopper Glacier north of Cooke City, Beartooth Mountains, Montana in 2001 showing rapid retreat of the ice mass. It has shrunk from a length of five miles to one mile long as the ice has melted.

Image: Left: After Morton, M.C., 2018, Revealing the ghosts of glaciers past; https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/revealing-ghosts-glaciers-past;

Right: Lussier, A., 2001, Grasshopper Glacier; http://glaciers.us/images/Lussier-Grasshopper.html.

Image: Left: After Morton, M.C., 2018, Revealing the ghosts of glaciers past; https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/revealing-ghosts-glaciers-past;

Right: Lussier, A., 2001, Grasshopper Glacier; http://glaciers.us/images/Lussier-Grasshopper.html.

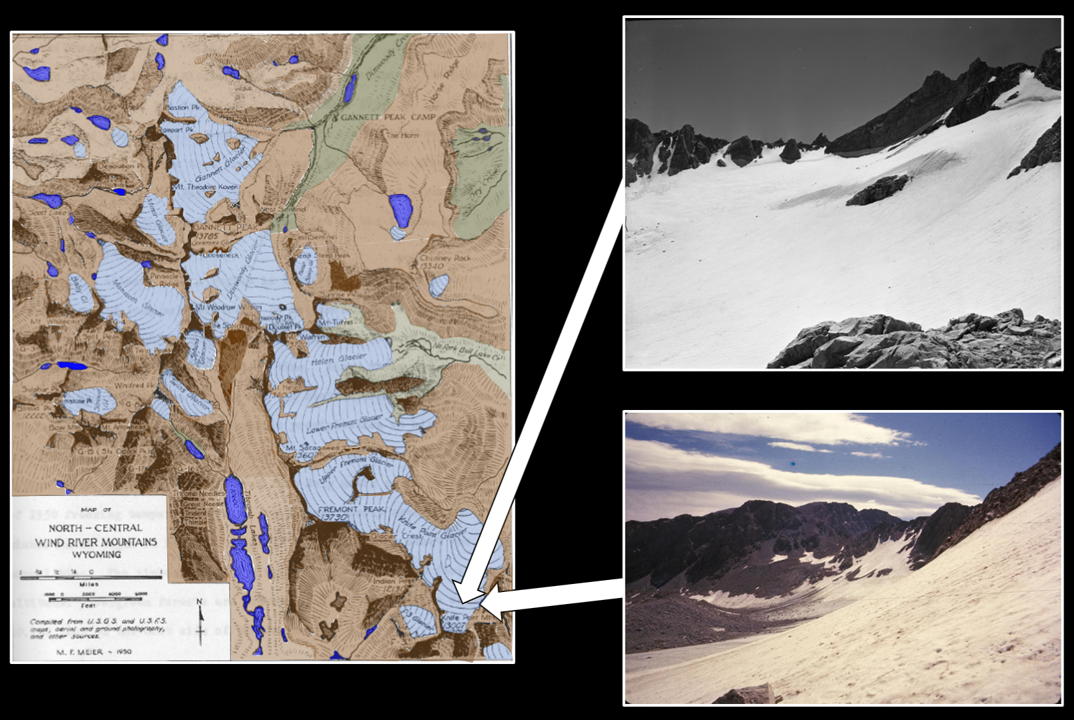

1950 Wind River Mountains glacier map, Wyoming. Knife Point glacier is in the southeast corner of the map (bottom right).

Image: Left: After Meier, M., 1951, Glaciers of the Gannett Peak-Fremont Peak Area, Wyoming: M.S. Thesis University of Iowa, Fig. 2, p. 3; https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6355&context=etd;

Right: http://glaciers.us/glacier-id/10461.html.

Image: Left: After Meier, M., 1951, Glaciers of the Gannett Peak-Fremont Peak Area, Wyoming: M.S. Thesis University of Iowa, Fig. 2, p. 3; https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6355&context=etd;

Right: http://glaciers.us/glacier-id/10461.html.

Wind River Mountains glaciers, Wyoming in 2009. Knife Point glacier is in the center right of the image

Image: After http://glaciers.us/glacier-id/10461.html

Image: After http://glaciers.us/glacier-id/10461.html

Things To Do

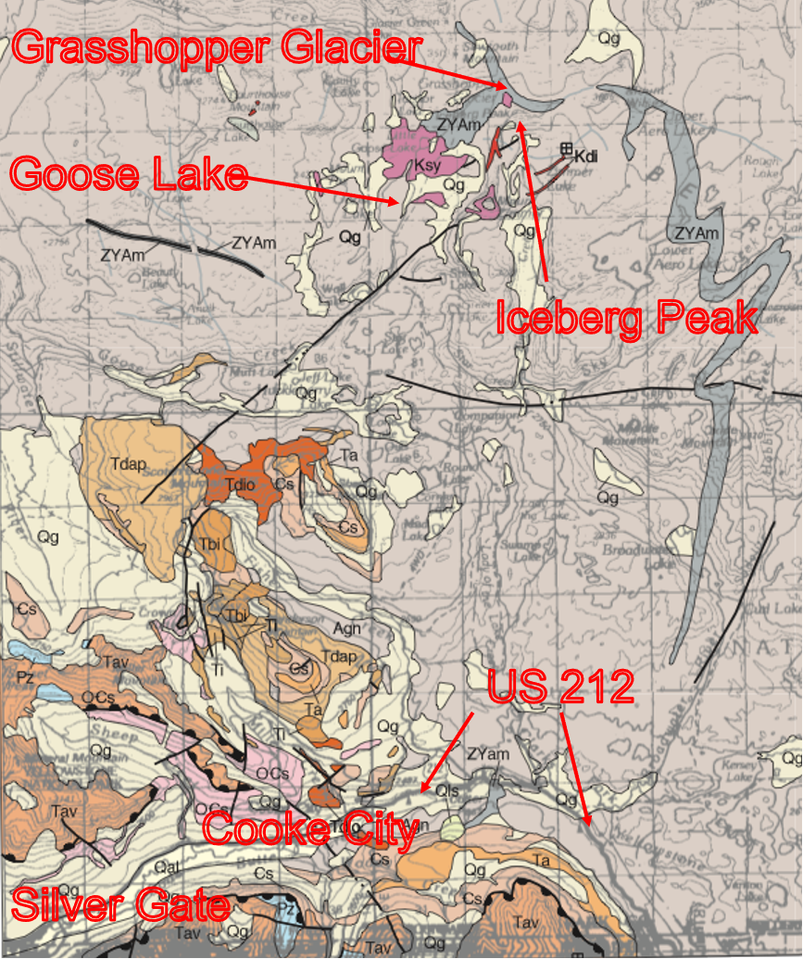

Our recommendation is to drive the Beartooth Mountain Highway (US 212) from Red Lodge to Cooke City. It is a slow, curvy and mountainous drive and has been called the most scenic road in the entire United States. Generally open from June into October, this highway provides access to gorgeous lakes, streams, waterfalls, alpine meadows filled with flowers, mountains, snowfields and small glaciers. Weather changes abruptly, so bring rain gear and warm clothes if you venture any distance from the car. You can certainly imagine a sudden storm blowing locusts onto the glaciers to be buried in icy graves. Also carry bear spray and mosquito repellent!

We do not recommend a trip to Grasshopper Glacier because of safety concerns on the glacier and the extremely poor condition of the Forest Service access road to the trailhead near Goose Lake. It is the roughest “road” we have ever experienced with large boulders embedded in the road. On a visit to Grasshopper Glacier during 2015, we did not find any grasshoppers in the glacier.

We do not recommend a trip to Grasshopper Glacier because of safety concerns on the glacier and the extremely poor condition of the Forest Service access road to the trailhead near Goose Lake. It is the roughest “road” we have ever experienced with large boulders embedded in the road. On a visit to Grasshopper Glacier during 2015, we did not find any grasshoppers in the glacier.

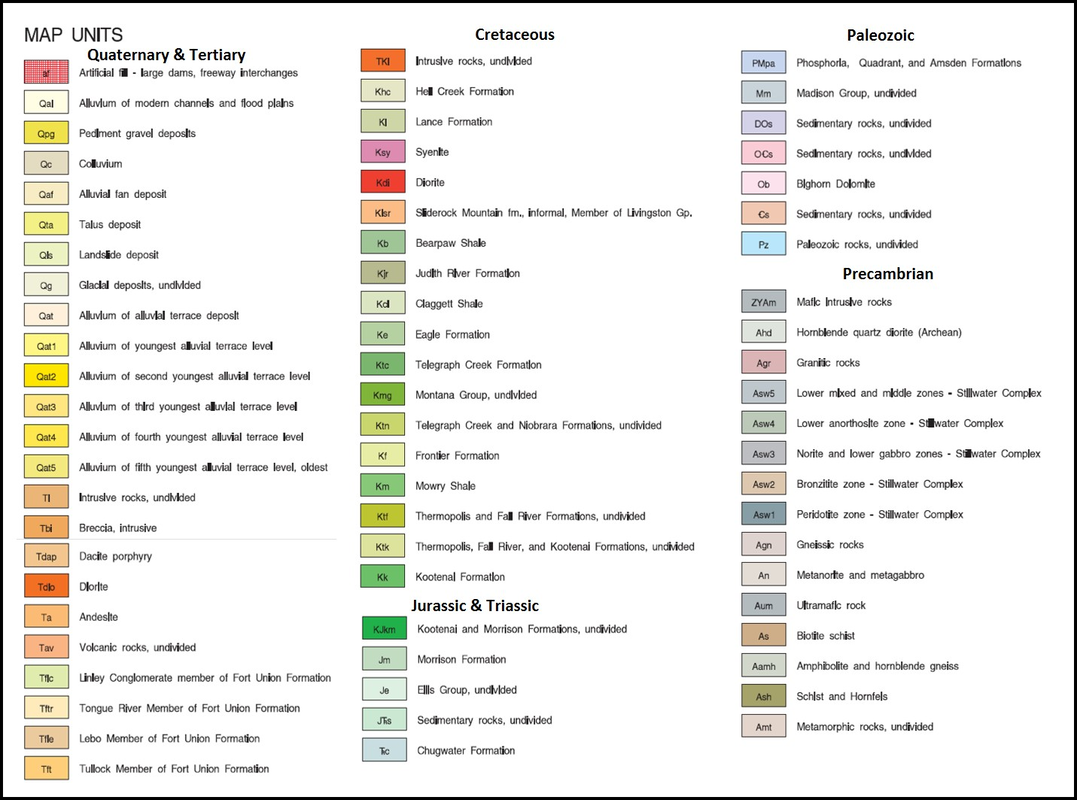

Geologic Map of Grasshopper Glacier and Cooke City area. Ksy in purple = Cretaceous Syenite, Kdi in red = Cretaceous Diorite, ZYAm in dark gray = Precambrian mafic intrusives. North and east portion of figure is Precambrian Granitic Gneiss in light mud color. Goose Lake area has historic remains from mining claims dating back to 1881(mbmg421-Custer.pdf).

Image: After Lopez, D.A., 2001, Preliminary Geologic Map of the Red Lodge 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 423; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/redLodge.pdf

Image: After Lopez, D.A., 2001, Preliminary Geologic Map of the Red Lodge 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 423; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/redLodge.pdf

The material on this page is copyrighted