Abandoned Smith Mine between Bear Creek and Washoe

Photo by Mark Fisher

Photo by Mark Fisher

Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Late 19th – early 20th century underground coal development at the northeastern corner of the Beartooth Mountains. A journey into the northwestern Bighorn Basin characterized by Tertiary coal beds, train-fueled development, and a large immigrant population. The eventual closure of the mines led to the abandonment of communities and the transformation of historic Red Lodge into a recreational gateway town to the Beartooth Mountains and Yellowstone National Park.

Southward view of the Red Lodge-Bearcreek region, northernmost Bighorn Basin. The Montana portion of the Original 100 Mile Trail and relocated Meeteetse Trail are shown by red dot and red dash lines respectively.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

History of Red Lodge and Bear Creek Area

James “Yankee Jim” George discovered coal along the east side of the Rock Creek Valley while exploring for gold in 1866. He attempted to enlist investors but was unsuccessful due to the discovery’s isolation (distance to market and lack of transportation) and location on Crow Indian land (1851 Fort Laramie Treaty). Coal development here would be delayed for two decades.

Important events occurred between 1870 and 1890 that opened the Rocky Mountain West to settlement and development. A key factor was the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act which changed the way the federal government dealt with native American tribes.

“That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty …” (16 Stat. 566; Rev. Stat. 2079, now 25 U.S.C. 71).

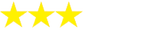

This law took away the ability of Indians to make treaties. The Crow territory cession agreements of 1880 and 1890 were examples of this new policy. The Crow gave away their land from the Yellowstone River to the Montana–Wyoming border for certain considerations.

Important events occurred between 1870 and 1890 that opened the Rocky Mountain West to settlement and development. A key factor was the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act which changed the way the federal government dealt with native American tribes.

“That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty …” (16 Stat. 566; Rev. Stat. 2079, now 25 U.S.C. 71).

This law took away the ability of Indians to make treaties. The Crow territory cession agreements of 1880 and 1890 were examples of this new policy. The Crow gave away their land from the Yellowstone River to the Montana–Wyoming border for certain considerations.

Tribal territory recognized by Laramie Treaty of 1851. The 1880 agreement (white dashed line) with the Crow opened the Red Lodge area to American and European emigrants after early 1882.

Image: After https://www.ndstudies.gov/threeaffiliated-tribal-overview.

Image: After https://www.ndstudies.gov/threeaffiliated-tribal-overview.

Red Lodge was formally established as a mail stop on the Meeteetse Trail in 1884. John Jeremiah “Liver-eating” Johnston’s cabin along Rock Creek served as the Post Office while he acted as the town’s first sheriff. The trail was built in 1881 by the U.S. military as a supply route from Meeteetse to Billings (Coulson). It was the first road built in the Bighorn Basin. The route was originally called the “100 Mile Trail “ which was the distance between Red Lodge, Montana and Meeteetse, Wyoming. The trail originally went through the towns in the Bear Creek Valley but was moved further west towards the mountains to avoid the wet gulches in the mining camps.

Johnston’s cabin in original location southeast of town and at the Chamber of Commerce Visitor Center at the northern edge of town (after 1986).

Image: Left: http://johnlivereatingjohnston.com/services; Right: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Liver-Eating_Johnson.

Image: Left: http://johnlivereatingjohnston.com/services; Right: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Liver-Eating_Johnson.

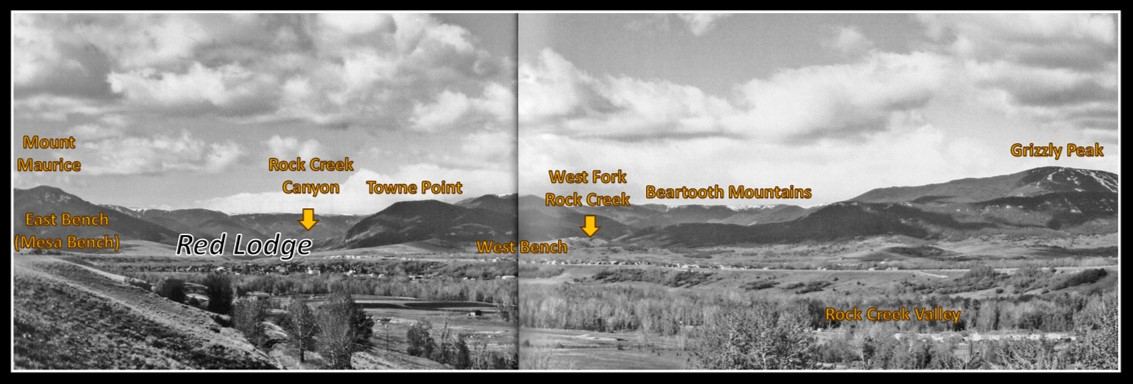

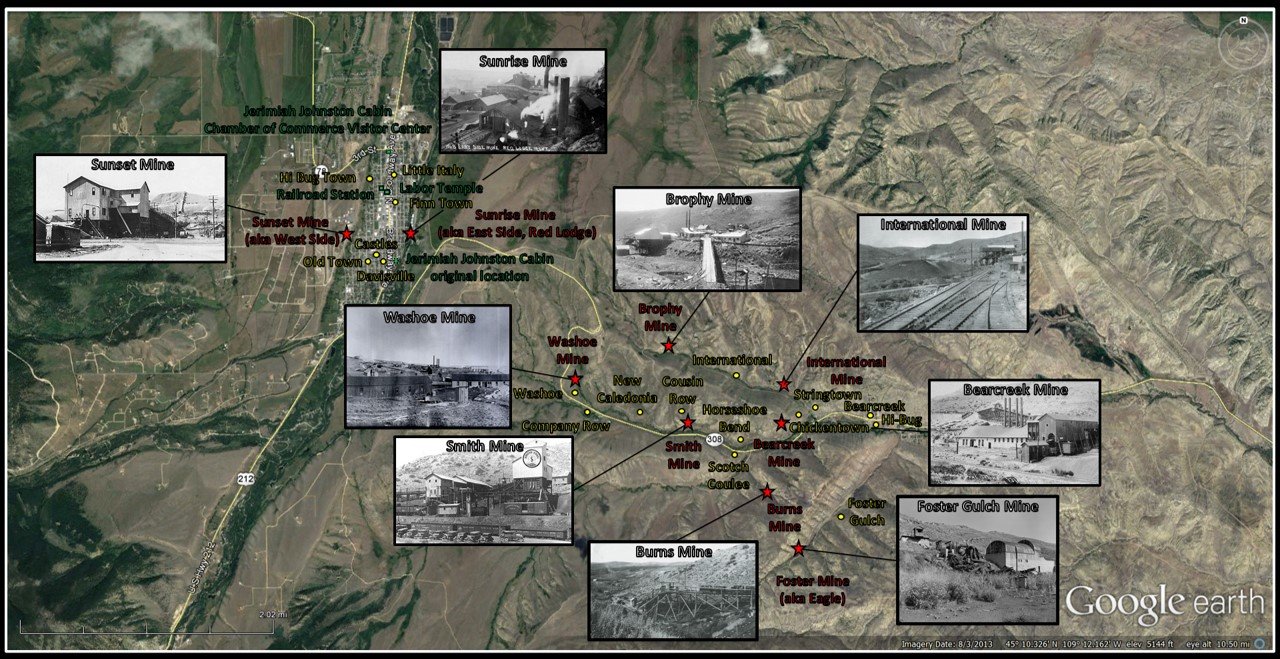

The earliest coal mining in Rock Creek Valley began in 1882. It was a small scale operation that produced coal for local consumption. The Rock Fork Coal Company opened the first commercial coal mine (Red Lodge Mine, aka East Side or Sunrise) in 1888. The mine was purchased the following year by the Northwestern Improvement Company a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The coal was now used by the railroads for locomotive boiler fuel, and by Red Lodge and Billings residents for heating fuel. The Rocky Fork & Cooke City Railway arrived in town in 1889. The spur line was acquired by the Northern Pacific (NP) in 1890. Train transportation sparked a boom in European immigration and coal production from 1893 to 1910.

The same coal beds were developed in the Bear Creek drainage to the east of Red Lodge. Commercial development here was delayed a decade longer due to the lack of rail transportation and the topographic barrier separating the districts. The Washoe Coal Company, a subsidiary of Anaconda Copper Company, opened and closed the first commercial mine along Keucking Creek (pronounced “Kicking”) in the district in 1892. High transportation costs due to the required wagon haul up and over the benches (Mesa, Roberts, and Rock Creek) separating the Bear Creek Valley from the Red Lodge train depot made mining unprofitable. Mining activity resumed 15 years later in 1907 with the impending arrival of the Montana, Wyoming, & Southern Railway (MW&S) to Bearcreek and Washoe. The MW&S was a privately held short line that began building from the Northern Pacific line in Bridger, Montana in 1904. The short line was originally called the Yellowstone Park Railroad (YPRR) based on their plans to lay track past the Cooke City gold mines and continuing onto Yellowstone Park. Several companies opened mines in the Bear Creek valleys during the 5-year railroad construction. The companies included the Montana Coal and Iron (Smith in Foster Gulch), Bear Creek Coal, Smokeless and Sootless Coal (aka Brophy in Virtue Gulch), and International Coal (in Virtue Gulch).

The same coal beds were developed in the Bear Creek drainage to the east of Red Lodge. Commercial development here was delayed a decade longer due to the lack of rail transportation and the topographic barrier separating the districts. The Washoe Coal Company, a subsidiary of Anaconda Copper Company, opened and closed the first commercial mine along Keucking Creek (pronounced “Kicking”) in the district in 1892. High transportation costs due to the required wagon haul up and over the benches (Mesa, Roberts, and Rock Creek) separating the Bear Creek Valley from the Red Lodge train depot made mining unprofitable. Mining activity resumed 15 years later in 1907 with the impending arrival of the Montana, Wyoming, & Southern Railway (MW&S) to Bearcreek and Washoe. The MW&S was a privately held short line that began building from the Northern Pacific line in Bridger, Montana in 1904. The short line was originally called the Yellowstone Park Railroad (YPRR) based on their plans to lay track past the Cooke City gold mines and continuing onto Yellowstone Park. Several companies opened mines in the Bear Creek valleys during the 5-year railroad construction. The companies included the Montana Coal and Iron (Smith in Foster Gulch), Bear Creek Coal, Smokeless and Sootless Coal (aka Brophy in Virtue Gulch), and International Coal (in Virtue Gulch).

Southwest view of Bear Creek Valley, 1917.

Image: After McNish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Frontispiece.

Image: After McNish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Frontispiece.

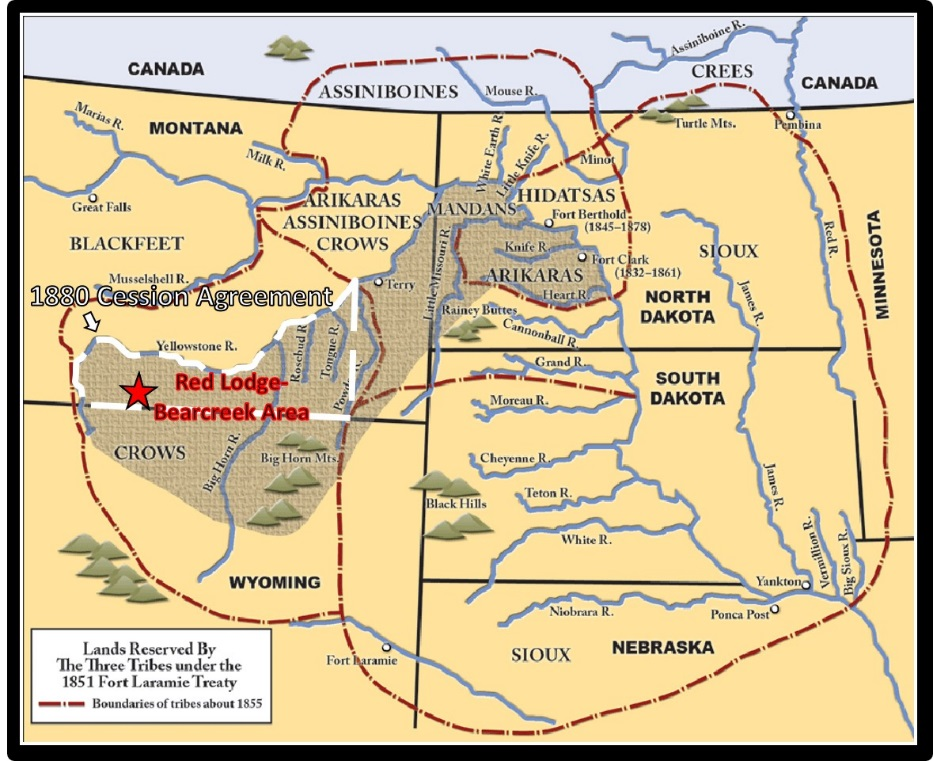

South view of Red Lodge

Image: After Clayton, J., 2008, Images of America: Red Lodge, Fig. on p. 10-11.

Image: After Clayton, J., 2008, Images of America: Red Lodge, Fig. on p. 10-11.

Train Routes that enabled communities and mining to grow.

Image: Base: After Axline, J., 1999, Something of a Nuisance Value: The Montana, Wyoming & Southern Railroad, 1905-1953: Montana the Magazine of Western History, Figure on p. 50; https://mhs.mt.gov/Portals/11/education/docs/CirGuides/Axline%20transportation.pdf; Red Lodge: http://www.nprha.org/lists/depot%20photos%20of%20the%20np/standard%20view1.aspx#InplviewHash5c14b654-2232-4af6-ac26-dce55344c415=; Laurel: https://billingsgazette.com/news/features/magazine/laurel-at-railroad-spurs-towns-growth/article_29abd2f3-4359-55f2-93cd-c13cbb63bc63.html; Bridger: http://www.nprha.org/lists/depot%20photos%20of%20the%20np/standard%20view1.aspx: McNeish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Figure on p. 18; NP Engine: https://mtmemory.org/digital/collection/p16013coll27/id/1217/; MW&S Engine: http://pnrarchive.org/Lists/Walt_Ainsworth_Short_Line_Photos/AllItems.aspx?Paged=TRUE&p_ID=1043&PageFirstRow=501&&View=%7B007C2384-AE69-4705-A5AA-90F915D2F5D2%7D.

Image: Base: After Axline, J., 1999, Something of a Nuisance Value: The Montana, Wyoming & Southern Railroad, 1905-1953: Montana the Magazine of Western History, Figure on p. 50; https://mhs.mt.gov/Portals/11/education/docs/CirGuides/Axline%20transportation.pdf; Red Lodge: http://www.nprha.org/lists/depot%20photos%20of%20the%20np/standard%20view1.aspx#InplviewHash5c14b654-2232-4af6-ac26-dce55344c415=; Laurel: https://billingsgazette.com/news/features/magazine/laurel-at-railroad-spurs-towns-growth/article_29abd2f3-4359-55f2-93cd-c13cbb63bc63.html; Bridger: http://www.nprha.org/lists/depot%20photos%20of%20the%20np/standard%20view1.aspx: McNeish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Figure on p. 18; NP Engine: https://mtmemory.org/digital/collection/p16013coll27/id/1217/; MW&S Engine: http://pnrarchive.org/Lists/Walt_Ainsworth_Short_Line_Photos/AllItems.aspx?Paged=TRUE&p_ID=1043&PageFirstRow=501&&View=%7B007C2384-AE69-4705-A5AA-90F915D2F5D2%7D.

Trains were the engine of development for Red Lodge and the Bear Creek Valley.

Cartoon by Ken Steele

Cartoon by Ken Steele

Major mines (red stars) and ethnic communities (yellow dots) in the Red Lodge-Bearcreek Districts.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Sunset, Sunrise, Bearcreek and Smith: https://miningartifacts.homestead.com/MontanaMines.html; Washoe, Brophy, Burns, and International, McNeish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Figure on p. 20, 22, 34, 39; Foster Gulch: Library of Congress @ https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.mt0185.photos/?sp=1.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Sunset, Sunrise, Bearcreek and Smith: https://miningartifacts.homestead.com/MontanaMines.html; Washoe, Brophy, Burns, and International, McNeish, J., 2009, Images of America: Bear Creek Valley, Figure on p. 20, 22, 34, 39; Foster Gulch: Library of Congress @ https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.mt0185.photos/?sp=1.

Geology of Red Lodge and Bear Creek Area

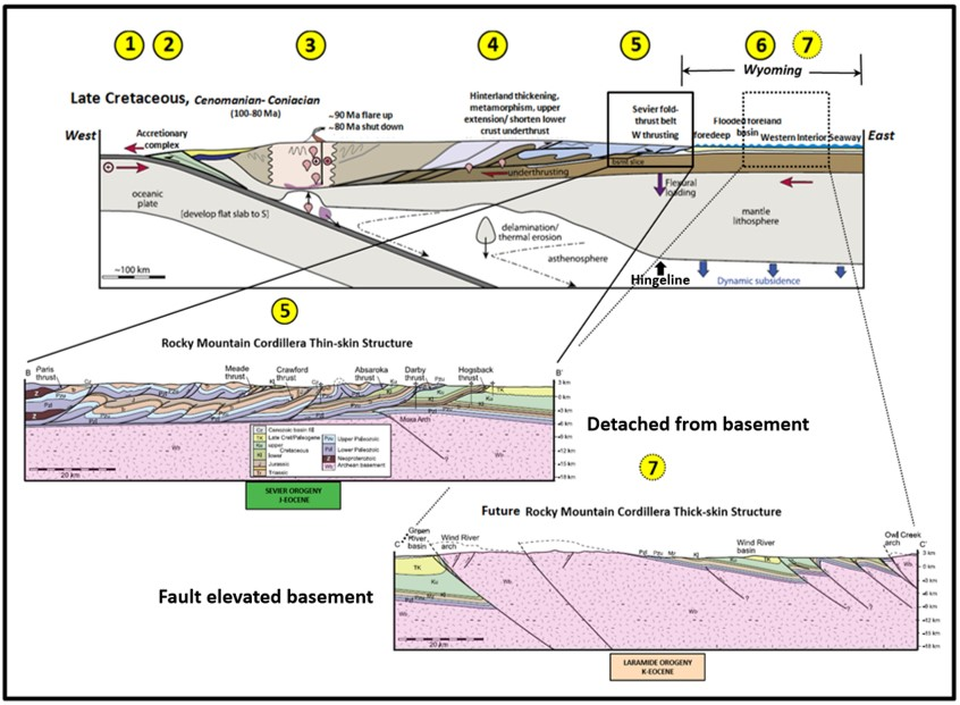

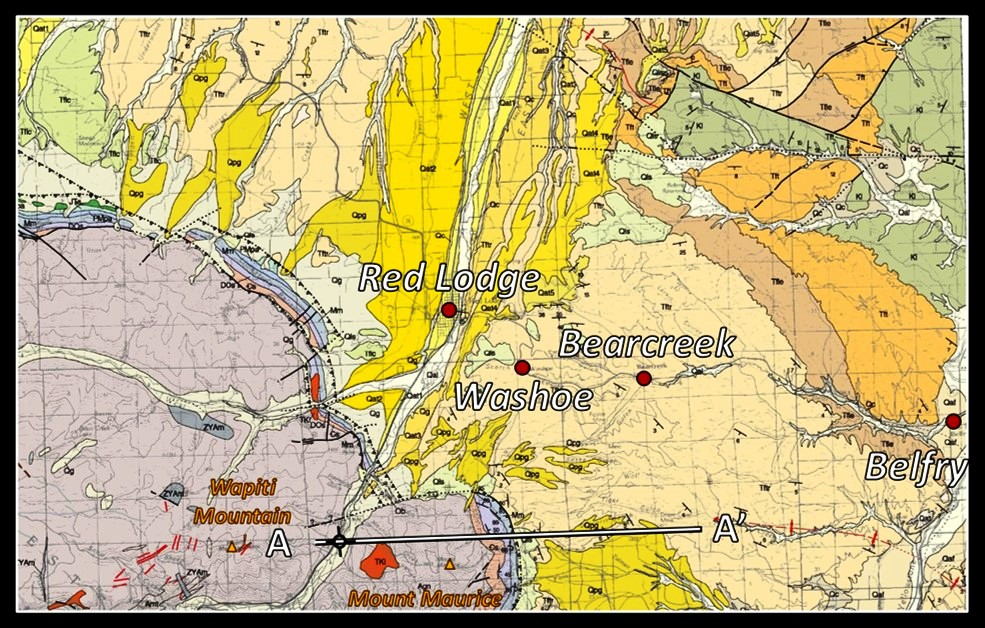

The coal beds are contained in the Paleocene Fort Union Formation. This unit was deposited during the Laramide Orogeny (70-55 million years ago) when the Beartooth Mountains were raised several thousand feet above the basin (about 60 million years ago). The mountain building tectonism was due to shallow subduction of the oceanic plate beneath western North America. The collision of the paleo-Pacific and North American plates began about 140 million years ago and produced two tectonic mountain systems, the “thin-skinned” Sevier (generally west of the “Hingeline” or tectonically thinned crust) and the “thick-skinned” Laramide (basement cored uplifts) orogens.

The Fort Union Formation is about 8,500 foot thick in the Red Lodge-Bearcreek area and is divided into three members. The stratigraphy of the rocks reflect the various depositional environments present during the mountain building. The lower member consists of 5,700 feet of variable yellowish shale and sandstone with no significant coal beds. These rocks were deposited by braided streams eroding the sedimentary overburden before major uplift exposed the Wyoming Craton basement rocks. The 825 foot thick middle unit consists of coal bearing units (7-9 beds) in shale and sandstones like those in the lower member. The coal beds formed from peat (woody organic material) deposited in humid swamps adjacent to streams. The upper member is 1,975 feet of sand and shale, barren of coal. The predominance of sandstone in this member, as well as the conglomerates deposited in fans along the mountain front, indicate the Beartooths were rapidly rising in late Paleocene. Older Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks dip steeply along the mountain front where younger Tertiary units (Eocene Willwood Formation) lap onto them with an angular unconformity in some locations.

The Fort Union Formation is about 8,500 foot thick in the Red Lodge-Bearcreek area and is divided into three members. The stratigraphy of the rocks reflect the various depositional environments present during the mountain building. The lower member consists of 5,700 feet of variable yellowish shale and sandstone with no significant coal beds. These rocks were deposited by braided streams eroding the sedimentary overburden before major uplift exposed the Wyoming Craton basement rocks. The 825 foot thick middle unit consists of coal bearing units (7-9 beds) in shale and sandstones like those in the lower member. The coal beds formed from peat (woody organic material) deposited in humid swamps adjacent to streams. The upper member is 1,975 feet of sand and shale, barren of coal. The predominance of sandstone in this member, as well as the conglomerates deposited in fans along the mountain front, indicate the Beartooths were rapidly rising in late Paleocene. Older Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks dip steeply along the mountain front where younger Tertiary units (Eocene Willwood Formation) lap onto them with an angular unconformity in some locations.

Late Cretaceous lithospheric cross section of western North America tectonics. The development of the Laramide basement -cored structures 1,000 miles from a plate margin is due to a shallowing of the subduction angle beneath North America about 70 million years ago. Events depicted include: 1) subduction zone at converging plate margins, 2) accretionary wedge (material sheared off descending plate and attached to the upper plate), 3) development of the volcanic arc ( developed above the rock melting point of the descending plate), 4) crustal thickening in the hinterland (includes accreted terrain and rifted cratonic crust), 5) formation of the Sevier fold and thrust belt localized at the Wyoming Craton western edge (close-up cross section B-B’), 6) Sedimentation into the Sevier foreland and Western Interior Seaway, and 7) the future location of the development of Laramide Arch structures (close-up cross section C-C’).

Image: After Yonkee, W.A. and Weil, A.B., 2015, Tectonic evolution of the Sevier and Laramide belts within the North American Cordillera orogenic system: Earth-Science Reviews 150, Fig. 6C, p. 542; Weil, A.B. and Yonkee, W.A., 2012, Earth and Planetary Science Letters 357–358, Fig. 2, p. 408.

Image: After Yonkee, W.A. and Weil, A.B., 2015, Tectonic evolution of the Sevier and Laramide belts within the North American Cordillera orogenic system: Earth-Science Reviews 150, Fig. 6C, p. 542; Weil, A.B. and Yonkee, W.A., 2012, Earth and Planetary Science Letters 357–358, Fig. 2, p. 408.

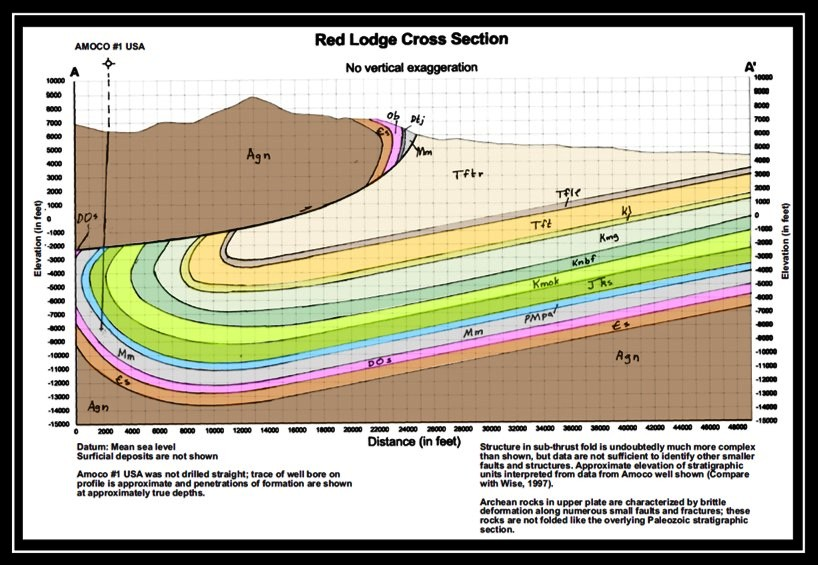

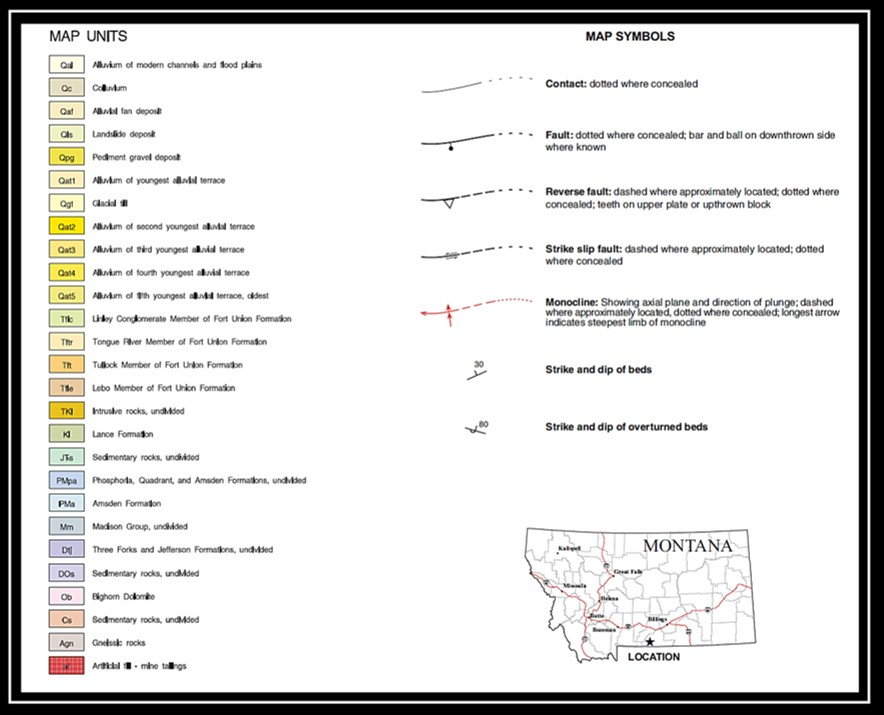

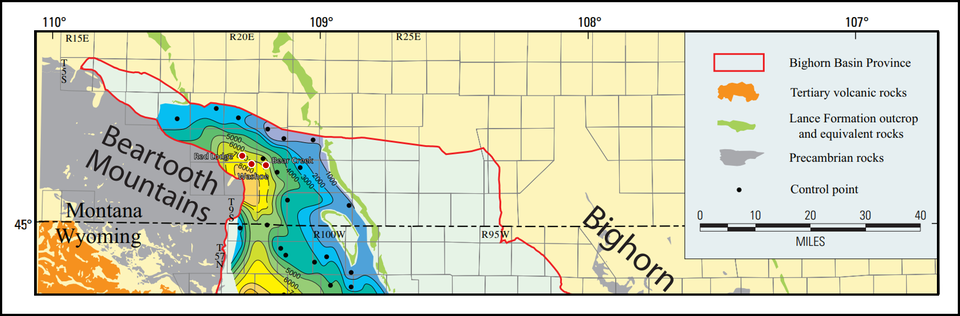

Geologic map of the Red Lodge Bearcreek area, structural cross section AA’, Red Lodge corner, and map and cross section index. The Fort Union Formation crops out in the light tan colored areas on the map. The Beartooth thrust overrides the basin up to seven and a half miles with a vertical separation on the basement of about 20,000 feet. The deepest part of the geologic basin in this area is under the edge of the Beartooth Uplift. Note Amoco dry hole drilled next to the Beartooth Highway almost across from the Rock Creek Resort.

Image: Lopez, D.A., 2005, Geologic map of the Red Lodge Area, Carbon County, Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Open-File Reports 524, scale 1:48,000; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf-open-files/mbmg524-redLodge.pdf.

Image: Lopez, D.A., 2005, Geologic map of the Red Lodge Area, Carbon County, Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Open-File Reports 524, scale 1:48,000; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf-open-files/mbmg524-redLodge.pdf.

Structure map on Cretaceous Fall River Sandstone (Dakota Sandstone), northern Bighorn Basin.

Image: After Mitchell, J.R., 2014, Petroleum Occurrences in Cretaceous-Age Reservoirs, Northern Bighorn Basin, Montana and Wyoming: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Search and Discovery Article #10633; http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2014/10633mitchell/ndx_mitchell.pdf.

Image: After Mitchell, J.R., 2014, Petroleum Occurrences in Cretaceous-Age Reservoirs, Northern Bighorn Basin, Montana and Wyoming: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Search and Discovery Article #10633; http://www.searchanddiscovery.com/documents/2014/10633mitchell/ndx_mitchell.pdf.

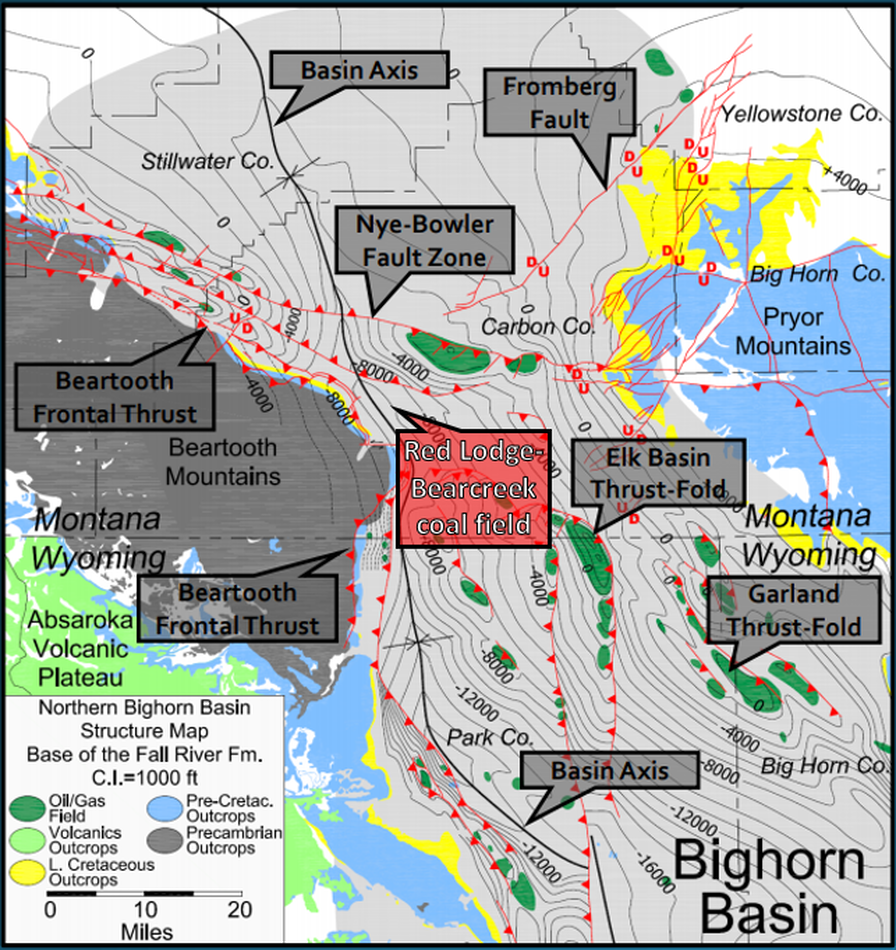

Isopach (thickness) map of Tertiary rocks in the northernmost Bighorn Basin. Maximum thickness occurs in the Washoe area at the Red Lodge corner (northeast) of the Beartooth Mountains.

Image: After Finn, T.M., Kirschbaum, M.A., Roberts, S.B., Condon, S.M., Roberts, L.N.R., and Johnson, R.C., 2010, Cretaceous–Tertiary Composite Total Petroleum System (503402), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana; in U.S. Geological Survey Bighorn Basin Province Assessment Team, 2010, Petroleum Systems and Geologic Assessment of Oil and Gas in the Bighorn Basin Province, Wyoming and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Digital Data Series DDS–69–V, Chapter 3, Fig. 17, p. 23; https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-069/dds-069-v/REPORTS/69_V_CH_3.pdf.

Image: After Finn, T.M., Kirschbaum, M.A., Roberts, S.B., Condon, S.M., Roberts, L.N.R., and Johnson, R.C., 2010, Cretaceous–Tertiary Composite Total Petroleum System (503402), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana; in U.S. Geological Survey Bighorn Basin Province Assessment Team, 2010, Petroleum Systems and Geologic Assessment of Oil and Gas in the Bighorn Basin Province, Wyoming and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Digital Data Series DDS–69–V, Chapter 3, Fig. 17, p. 23; https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-069/dds-069-v/REPORTS/69_V_CH_3.pdf.

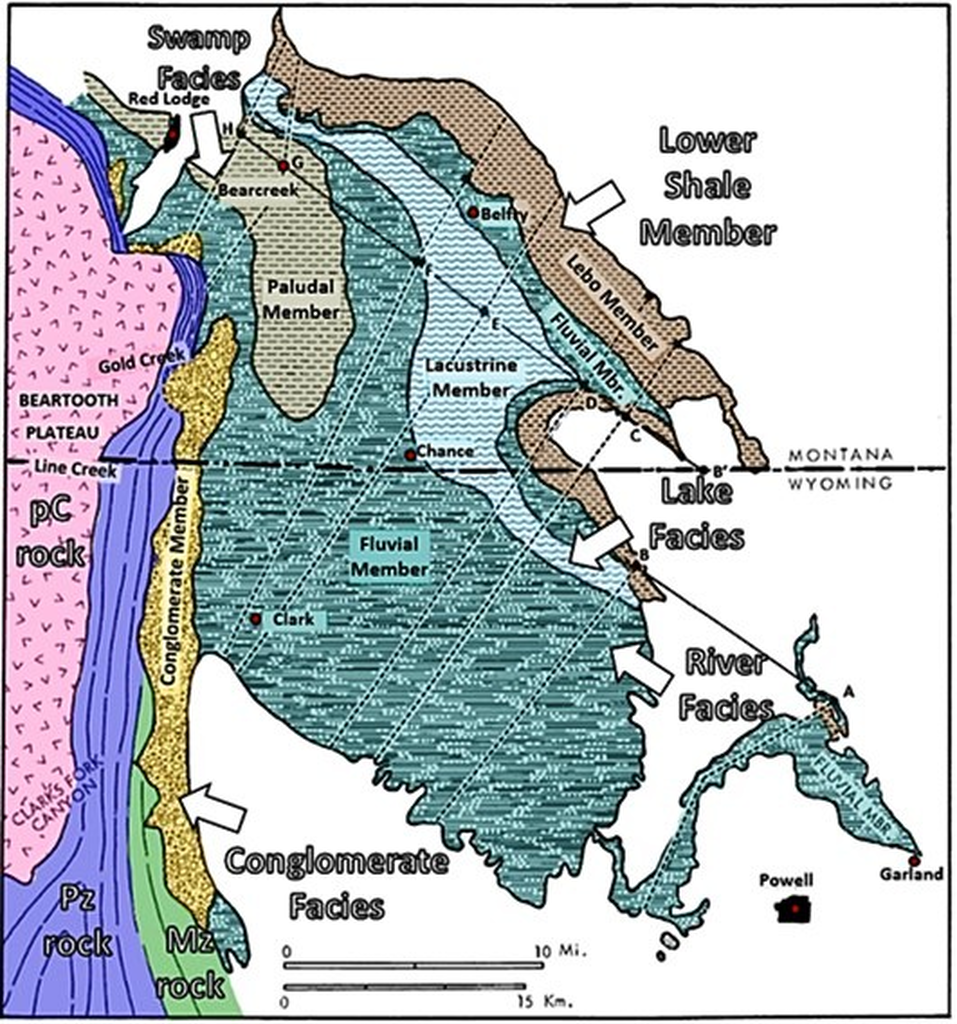

Outcrop map showing the members making up the Fort Union and lower Willwood Formations (Puercan through Clarkforkian Ages) of the Clark's Fork Basin. Coal beds are concentrated in the paludal member. Lines AB and B'H were followed in constructing the cross section below, and these are shown as a solid line. Dashed lines roughly perpendicular to these are lines of measured sections or of observations and trigonometric tabulations used to construct the section at each point.

Image: After Hickey, L.J., 1980, Paleocene Stratigraphy and Flora of the Clarks Fork Basin: in Gingerich, P.D., Editor, Early Cenozoic Paleontology and Stratigraphy of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming: Papers on Paleontology No. 24, Fig. 1, p. 35; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6f57/e3dbb62739eac831f5900f77024485d11f93.pdf.

Image: After Hickey, L.J., 1980, Paleocene Stratigraphy and Flora of the Clarks Fork Basin: in Gingerich, P.D., Editor, Early Cenozoic Paleontology and Stratigraphy of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming: Papers on Paleontology No. 24, Fig. 1, p. 35; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6f57/e3dbb62739eac831f5900f77024485d11f93.pdf.

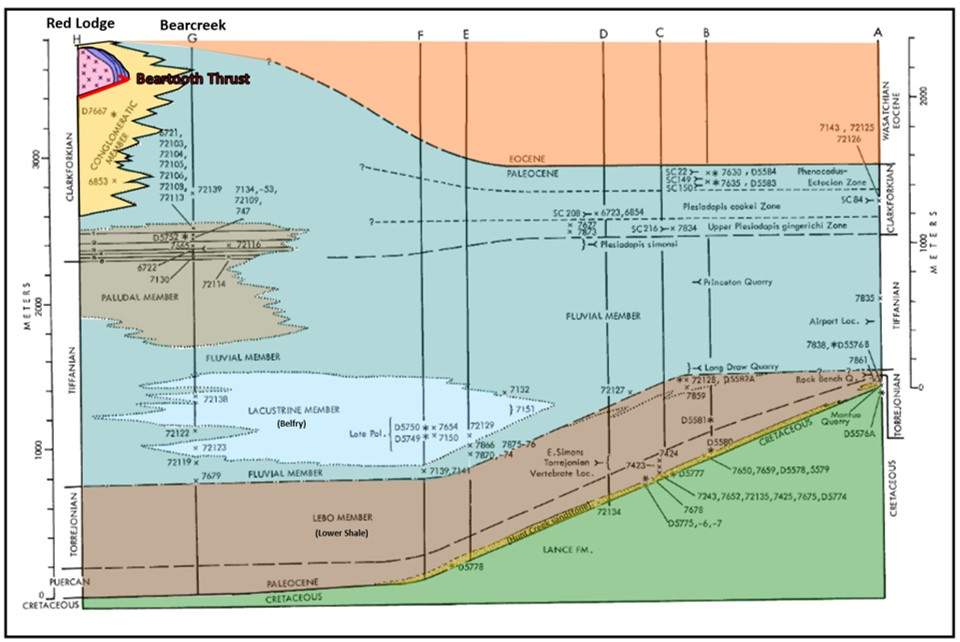

Fort Union Formation facies cross section in the northern Bighorn Basin, Montana and Wyoming. Red Lodge and Bear Creek Valley coal mines are developed in the paludal (marsh) facies. Positions of megafossil plant sites (x), pollen sites (*), and selected mammal localities (brackets).

Image: After Hickey, L.J., 1980, Paleocene Stratigraphy and Flora of the Clarks Fork Basin: in Gingerich, P.D., Editor, Early Cenozoic Paleontology and Stratigraphy of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming: Papers on Paleontology No. 24, Fig. 2, p. 36; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6f57/e3dbb62739eac831f5900f77024485d11f93.pdf.

Image: After Hickey, L.J., 1980, Paleocene Stratigraphy and Flora of the Clarks Fork Basin: in Gingerich, P.D., Editor, Early Cenozoic Paleontology and Stratigraphy of the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming: Papers on Paleontology No. 24, Fig. 2, p. 36; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6f57/e3dbb62739eac831f5900f77024485d11f93.pdf.

Generalized column of coal bearing middle unit of the Fort Union Formation in the Red Lodge-Bearcreek districts. Location of structural cross section AA’ is shown on the Fort Union Formation outcrop map.

Image: After Roberts, S.B. and Rossi, G.S., 1999, A Summary of Coal in the Fort Union Formation (Tertiary), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana; in 1999 Resource Assessment of Selected Tertiary Coal Beds and Zones in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Great Plains Region, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625-A, Part V, Chapter SB, Fig. SB-12; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1625a/Chapters/SB.pdf.

Image: After Roberts, S.B. and Rossi, G.S., 1999, A Summary of Coal in the Fort Union Formation (Tertiary), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana; in 1999 Resource Assessment of Selected Tertiary Coal Beds and Zones in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Great Plains Region, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625-A, Part V, Chapter SB, Fig. SB-12; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1625a/Chapters/SB.pdf.

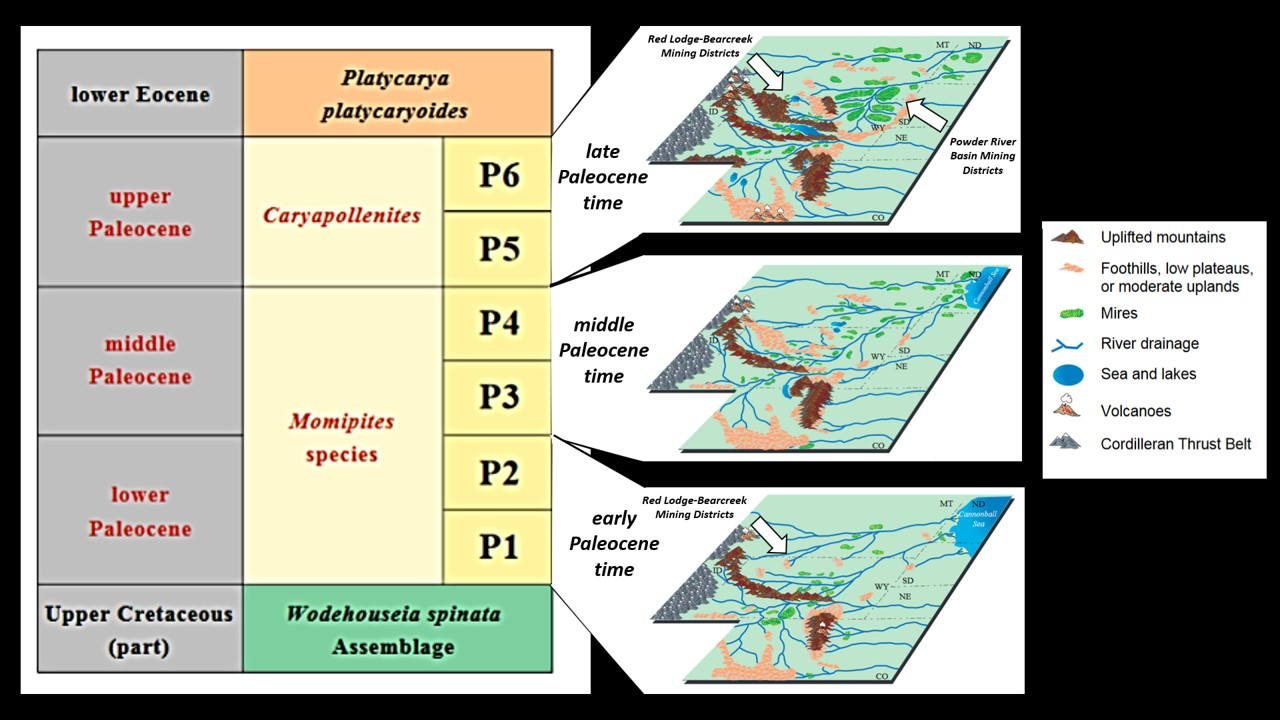

Left: Palynostratigraphy of the Fort Union Formation and adjacent rocks showing biozones defined by the occurrence of fossil pollen and spores. Right: Paleocene paleogeography. The geological age of the coal was determined using palynology and biozones that are identified based on fossil pollen that is found only in certain intervals in Paleocene rocks. The palynostratigraphic zonation for the Powder River Basin places the Tullock member in zones P1 and P2, the Lebo member in zones P3 and P4, and the Tongue River member in zones P5 and P6. Major development of important coal beds occurs in the P5 and P6 biozones in both the Northern Bighorn and Powder River basins.

Image: After Flores, R.M. and Nichols, D.J.,1999 , Introduction: in U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625-A, Figs. IN-10, 13,14,15; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1625a/Chapters/IN.pdf.

Image: After Flores, R.M. and Nichols, D.J.,1999 , Introduction: in U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625-A, Figs. IN-10, 13,14,15; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1625a/Chapters/IN.pdf.

Reconstruction of a Paleocene swamp with an extinct swamp thing.

Cartoon by Ken Steele

Cartoon by Ken Steele

Map of coal bed units beneath Red Lodge and Bearcreek mining districts. Mine (yellow double letter with mining symbol) and outcrop (white single letter) section locations are shown. Coal beds are numbered one through six (green).

Image: After Woodruff, E.G., 1909, The Red Lodge Coal Field, Montana, p. 92-107, Plate VI: in Campbell, M.R., Contributions to economic geology, 1907, Part II, Coal and lignite--Coal Fields of North Dakota and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 341-A; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0341a/report.pdf.

Image: After Woodruff, E.G., 1909, The Red Lodge Coal Field, Montana, p. 92-107, Plate VI: in Campbell, M.R., Contributions to economic geology, 1907, Part II, Coal and lignite--Coal Fields of North Dakota and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 341-A; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0341a/report.pdf.

Lithologic sections of numbered coal beds in Red Lodge-Bearcreek area. Locations of sections are indicated by letter at the top of columns and displayed on map shown above. Double letter locations are mine sites.

Image: After Woodruff, E.G., 1909, The Red Lodge Coal Field, Montana, p. 92-107, Plate VI: in Campbell, M.R., Contributions to economic geology, 1907, Part II, Coal and lignite--Coal Fields of North Dakota and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 341-A; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0341a/report.pdf.

Image: After Woodruff, E.G., 1909, The Red Lodge Coal Field, Montana, p. 92-107, Plate VI: in Campbell, M.R., Contributions to economic geology, 1907, Part II, Coal and lignite--Coal Fields of North Dakota and Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 341-A; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0341a/report.pdf.

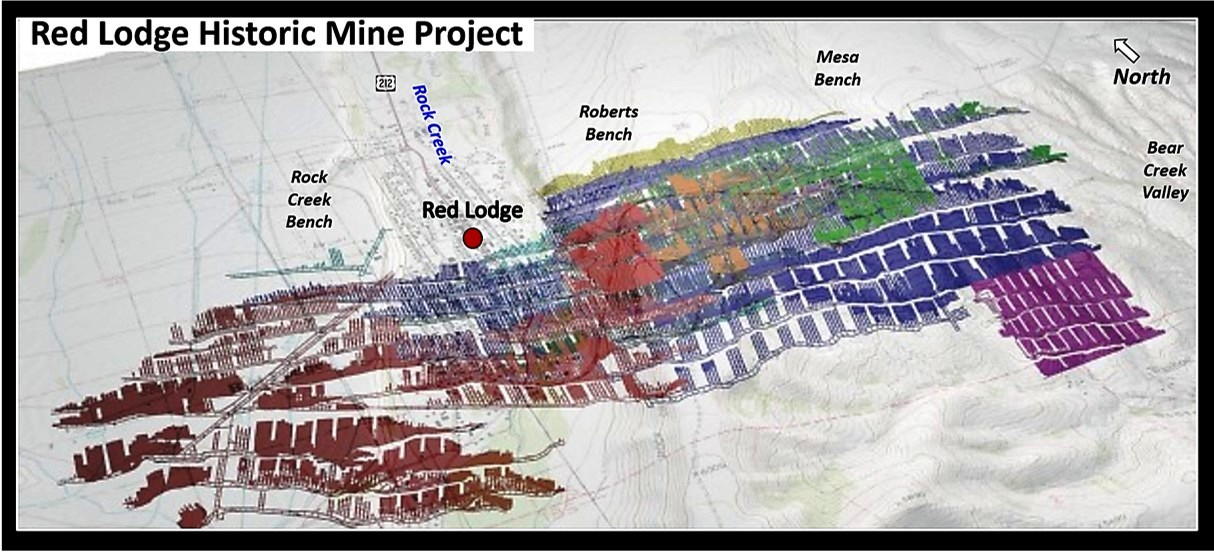

Map of Red Lodge Bearcreek subsurface mine tunnels superimposed on a surface topographic map of the region. Colors represent mined numbered coal beds. The rocks are dipping to the southwest (bottom left). Color code: red - Bed 1, orange - Bed 1.5, yellow – Bed 2, green – bed 3, dark blue – Bed 4, light blue - Bed 4.5, purple – Bed 5.

Image: After Pickett, M., 2011, MSUB College of Technology students map Red Lodge mines; https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/msub-college-of-technology-students-map-red-lodge-mines/article_ee582b16-fddf-5d7f-aa78-470151760a06.html.

Image: After Pickett, M., 2011, MSUB College of Technology students map Red Lodge mines; https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/msub-college-of-technology-students-map-red-lodge-mines/article_ee582b16-fddf-5d7f-aa78-470151760a06.html.

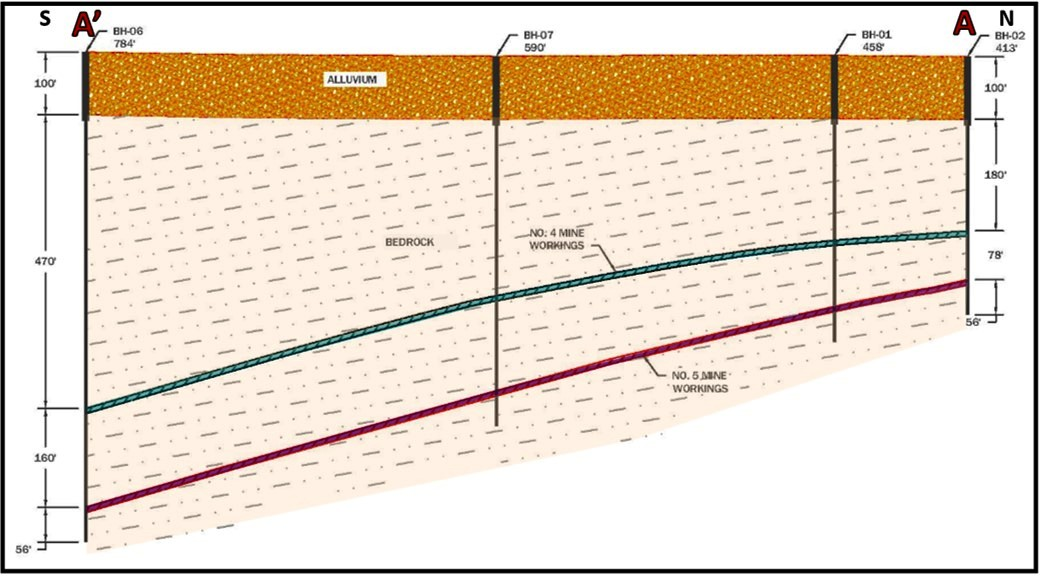

Montana Department of Environmental Quality Red Lodge public meeting presentation, 2014. Digital mine tunnel 3D map with location of eight cored drill holes shown. Top: perspective view of coal mine tunnels and drill hole locations. Bottom: cross section AA’ of coal beds 4 and 5.

Image: After MT DE, Abandoned Mines Lands Division slides 7 (top) and 9 (bottom); http://deq.mt.gov/Portals/112/Land/AbandonedMines/documents/ProjectDocuments/RedLodge/RL-TOWNCOUNCIL-PRESENTATION-062414.pdf.

Image: After MT DE, Abandoned Mines Lands Division slides 7 (top) and 9 (bottom); http://deq.mt.gov/Portals/112/Land/AbandonedMines/documents/ProjectDocuments/RedLodge/RL-TOWNCOUNCIL-PRESENTATION-062414.pdf.

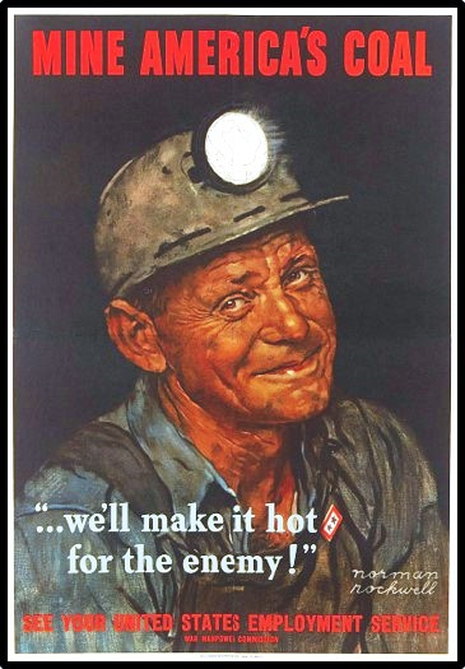

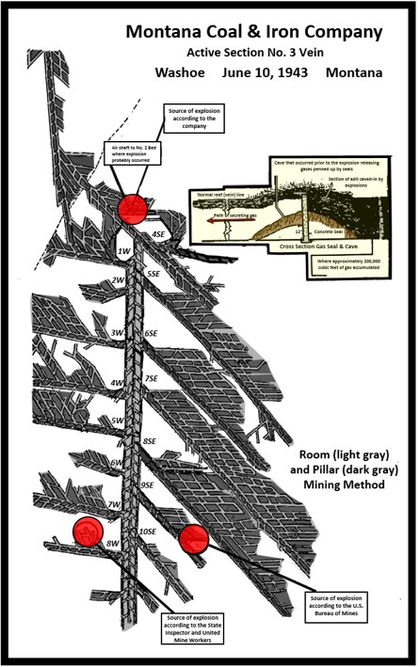

The presence of coal made the towns of Red Lodge and the Bear Creek valley possible. The coming of trains allowed them to develop and grow. The Great Depression and decreased demand for coal caused many of the mines to close. Anaconda Copper began electrification of their Butte and Anaconda smelting operations in 1912 with the formation of the Montana Power Company. New economic competition arose as the Northern Pacific began surface mining of coal in the Powder River Basin in 1924. Demand for coal further declined with the nation’s development and conversion to hydrocarbon power in the mid-twentieth century. The Smith Mine No. 3 explosion, which cost 74 miners lives, was the worst mine disaster in Montana history. The disaster occurred 18 days after President Roosevelt had signed the 48-hour workweek executive order to support the war effort. On that Saturday morning, 7,000 feet below the surface, 92 percent of the fatalities were first or second generation immigrants answering the call of their adopted land. The accident further dampened underground coal mining.

Left: World War II poster by Norman Rockwell. Right: Underground workings at Smith Mine Number 3 with possible ignition sites of the March 27, 1943 explosion. The explosion was caused by ignition of methane gas, but no consensus was reached on the source or location of the gas.

Image: Left: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/476818679273975382/; Right: After http://www.historicmapworks.com/Buildings/index.php?state=MT&city=Red%20Lodge%20vicinity&id=2152.

Image: Left: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/476818679273975382/; Right: After http://www.historicmapworks.com/Buildings/index.php?state=MT&city=Red%20Lodge%20vicinity&id=2152.

Little remains of the communities that flourished in the Bear Creek Valley during the coal mining boom. Most of the structures were either moved or demolished. The original Washoe Coal Company Mine office (Jeff McNeish, 2009, Bear Creek Valley) along with a few houses in the company town of Washoe still remain. The Bear Creek Saloon & Steakhouse anchor what remains of Bearcreek. Parimutuel pig racing occurs in the summer months to the delight of diners. The restaurant funds a college scholarship for local area students with their share of the take.

Top left: Smith Mine, Top right: Washoe Quilt Shoppe (closed) in Washoe Coal Company Mine Office building; Bottom left: Bear Creek Saloon & Steakhouse, Bottom right: pig racing at Bear Creek Downs.

Image: Top left: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/years-ago-the-smith-mine-disaster-decimated-the-small-montana/article_9bacd94f-a98f-5386-a408-2c93204da392.html; Top right: https://www.flickr.com/photos/outlawpete/7965461518; Bottom left: https://www.allredlodge.com/events/bear_creek_saloon_pig_races.php; Bottom right: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/pig-racing-in-bearcreek/collection_248f6cb4-90df-5555-9da5-51922d10ef77.html.

Image: Top left: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/years-ago-the-smith-mine-disaster-decimated-the-small-montana/article_9bacd94f-a98f-5386-a408-2c93204da392.html; Top right: https://www.flickr.com/photos/outlawpete/7965461518; Bottom left: https://www.allredlodge.com/events/bear_creek_saloon_pig_races.php; Bottom right: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/pig-racing-in-bearcreek/collection_248f6cb4-90df-5555-9da5-51922d10ef77.html.

The Town of Red Lodge survived the depression in part by the passage of the Leavitt National Park Approach Act (H.R. 12404). This bill funded the construction of the Beartooth Highway to Yellowstone Park that began construction in 1931. The highway became the northeast entrance road to Yellowstone National Park and was the only roadway built under the act. Other entrepreneurs managed to survive by marketing homemade moonshine labeled as “syrup” or “cough syrup” to communities from San Francisco to Chicago. The 18th Prohibition Amendment had gone into effect in 1919 and was not repealed until 1933 with the 21st Amendment. Transformation to a tourist and recreational destination was completed with the opening of the Grizzly Peak Ski resort in 1970 (now Red Lodge Mountain).

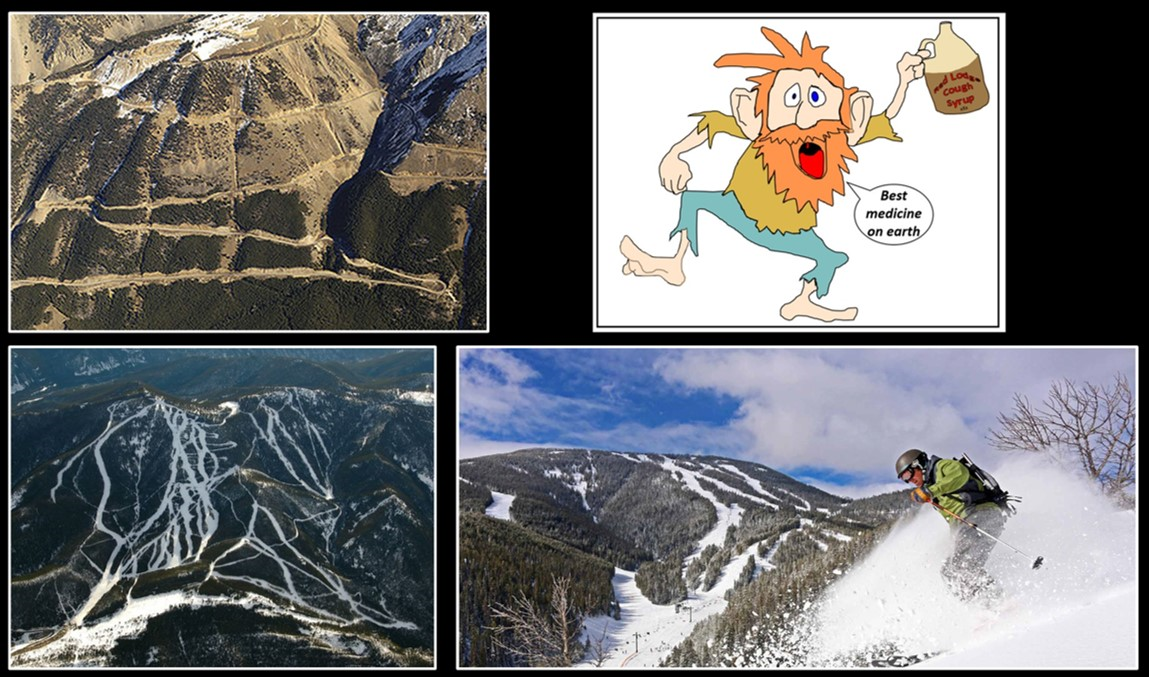

Top left: Beartooth Highway switchbacks, Top right: Bootleg Red Lodge Syrup, Bottom: Red Lodge Mountain ski area.

Images: Top Left: Highway: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/06jul/03.cfm; Top right: by Ken Steele; Bottom left: Red Lodge Mountain: French, B., 2016, Billings Gazette; https://billingsgazette.com/outdoors/red-lodge-mountain-seeking-new-investors/article_6b1603f0-6a85-54b2-95dc-d74ca81eafa6.html, Bottom right: Red Lodge Mountain; https://www.redlodgemountain.com/mountain/the-mountain/.

Images: Top Left: Highway: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/publicroads/06jul/03.cfm; Top right: by Ken Steele; Bottom left: Red Lodge Mountain: French, B., 2016, Billings Gazette; https://billingsgazette.com/outdoors/red-lodge-mountain-seeking-new-investors/article_6b1603f0-6a85-54b2-95dc-d74ca81eafa6.html, Bottom right: Red Lodge Mountain; https://www.redlodgemountain.com/mountain/the-mountain/.

Things To Do

The Red Lodge area is just gorgeous, and the food is great. My two favorite day hikes are up East Rosebud Creek as far as you want to go starting at East Rosebud Lake, and the hike up to Glacier Lake starting at the end of the Rock Creek valley. There are scenic spires and palisades on a hike up South Fork Grove Creek which is south of Red Lodge.

East Rosebud Hike

East Rosebud Creek and Trail

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

Just a gorgeous hike that should put goosebumps on your arms. At Roscoe (Grizzly Bar), take East Rosebud Road up East Rosebud Creek. After leaving Roscoe you will be driving past moraines from the Pinedale Glaciation and past MacKay Dome Oil Field (private land) that is on the ridge between the East and West Rosebud drainages. Drive this gravel and paved road a total of 14 miles or about 30 minutes to East Rosebud Lake that is surrounded by private cabins (Alpine). The Forest Service trailhead is to the left or east side of the lake. This trail eventually goes all the way over the top of the Beartooths and meets highway US 212 near Cooke City, which makes this a popular multi-day backpacking hike coming from the top. A great day hike destination is up to Elk Lake that is 6.5 miles round trip with an 800 foot elevation gain (3 to 4 hours total). This trail has Huckleberries. Take bear spay. What a special place!

Glacier Lake Hike

Glacier Lake in Beartooths on July 24

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

It is one of the most popular hikes in the Beartooths and for good reason. It is another goosebumps on the arms hike. It is that pretty! Take US 212 southwest from Red Lodge about 11 miles, turn right on Road 2421 for the Main Fork of Rock Creek. At this turnoff there is a sign labeled "campgrounds" for Parkside CG, Greenough Lake CG and Limberpine CG. Travel on paved Forest Service Road for about one mile, cross bridge over Rock Creek, pass Limberpine Campground turnoff and immediately turn left on gravel road up Rock Creek (not Hellroaring). Drive on a rough, but not terrible Forest Service road for about 8 miles to the end of the road. Be patient, this gravel road will take 30 to 40 minutes to drive. High clearance vehicle would be helpful for the last stretch. Trail to Glacier Lake is 3.8 miles round trip with 1,100 feet of vertical climb and 200 feet vertical descent to lake. There can be significant snow on the trail up high into early July. The lake has a small dam that was built to hold additional irrigation water. Weather changes quickly here. Take rain gear and bear spray just in case. Bring water shoes if you want to cross the creek to access Little Glacier Lake and Emerald Lake.

South Fork Grove Creek Hike

Palisades and spires along South Fork Grove Creek. Rocks are steeply dipping carbonate beds of the Mississippian Madison and Ordovician Bighorn Formations. View to the east with the Northern Bighorn Basin in the distance.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

The attraction on this hike are the spires and cliffs of steeply dipping carbonates. The trail is actually a steep old road that climbs across recently acquired BLM land to the Forest Service. The old road/trail runs mainly east-west and connects to the Forest Service “Face of the Mountain Trail” that runs north-south. Nice hike in May and June when other trails are still covered in snow. Access to the trailhead is via the Meeteetse Trail Road from Red Lodge. This dirt access road is slick when wet. Take US 212 southwest out of Red Lodge. At the south edge of town, just past the turnoff for Red Lodge Mountain Ski Area, take a left (east) on Meeteetse Trail Road. Road heads mostly south along the front of Mount Maurice. At about 7-1/2 miles (about one mile past North Grove Creek access) take a right at fork and go ¼ mile to parking area. Hike as little or far as you want up South Grove Creek drainage. There are remains of an old cabin or two and multiple abandoned roads to explore. The Tolman Flats topo map shows a prospect symbol near the drainage divide with Gold Creek.

The material on this page is copyrighted