Mountain goats along Beartooth Highway

Photo by Mark Fisher

Photo by Mark Fisher

Wow Factor (5 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (5 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Hairpin curves across a high mountain plateau of ancient rocks, sculpted by Pleistocene glacial ice into cirques and hanging valleys with abundant lakes and breath taking vistas.

The Beartooth Highway has been called “the Highway to the Sky,” “a Drive Along the Roof of the Rockies,” “the Top of the World” or simply “the most beautiful drive in America." The U.S. Department of Transportation recognized these unique qualities and designated a 68 mile section of U.S. 212 in Montana and Wyoming as an “All American Road” in June 2000. Travel over the eastern edge of the Beartooth Mountains encounters rocks that are evidence of some of the oldest and youngest processes on Earth.

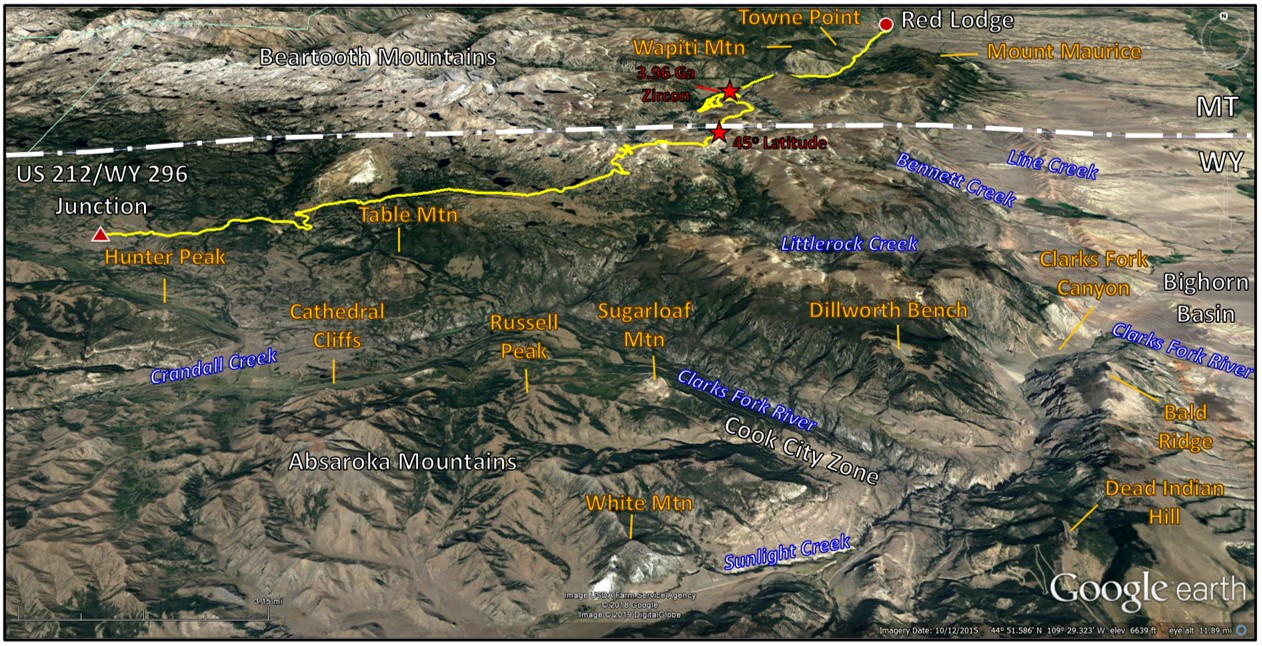

North aerial view of the Beartooth Highway area. The Beartooth All American Road from the Chief Joseph Scenic Byway junction (red triangle) to Red Lodge, MT (red dot) is shown by the yellow line. Red stars mark the locations of the 45th Parallel and the discovery site of the 4 billion year old zircon.

Image: Google Earth.

Image: Google Earth.

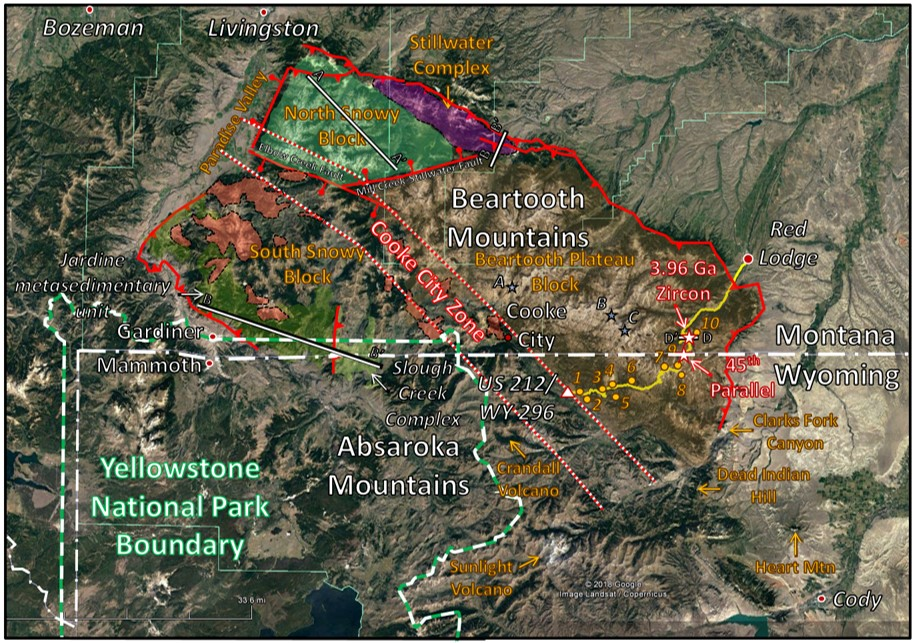

Major structural features of the Beartooth Uplift. Route on U.S. 212 shown by yellow line. Sites of interest shown by gold dots and numbered: (1) Lake Creek Falls & CCC Bridge, (2) Clarks Fork Valley Overlook, (3) Pilot & Index Peak Overlook, (4) Clay Butte Lookout Tower, (5) Beartooth Falls, (6) Top of the World Store, (7) West Summit & Beartooth Pass Overlook, (8) Gardiner Lake Pullout & Trailhead, (9) Summer Ski School, (10) Rock Creek Vista Point & Trailhead. Faults shown by red lines, reverse faults have teepees on the uplifted block, normal faults have stick and ball on the downthrown block. Yellowstone Park boundary shown by green and white line. Tertiary intrusions shown by pink polygons. Glaciers with extinct Rocky Mountain locusts shown by light blue stars: (A) Grasshopper Glacier West, (B) Hopper Glacier, and (C) Grasshopper Glacier East. Location of the 45th Parallel (midway between the North Pole and the Equator) and the 4 billion year old zircon shown by red outlined white stars. Cross section locations are labeled and shown by black outlined white lines.

Image: Google Earth; Data: After Van Gosen, B.S., The Life Cycle of Gold Deposits Near the Northeast Corner of Yellowstone National Park – Geology, Mining History and Fate: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1717M, Fig. 3, p.435; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1717/

Image: Google Earth; Data: After Van Gosen, B.S., The Life Cycle of Gold Deposits Near the Northeast Corner of Yellowstone National Park – Geology, Mining History and Fate: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1717M, Fig. 3, p.435; https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1717/

Geology of the Beartooth Mountains

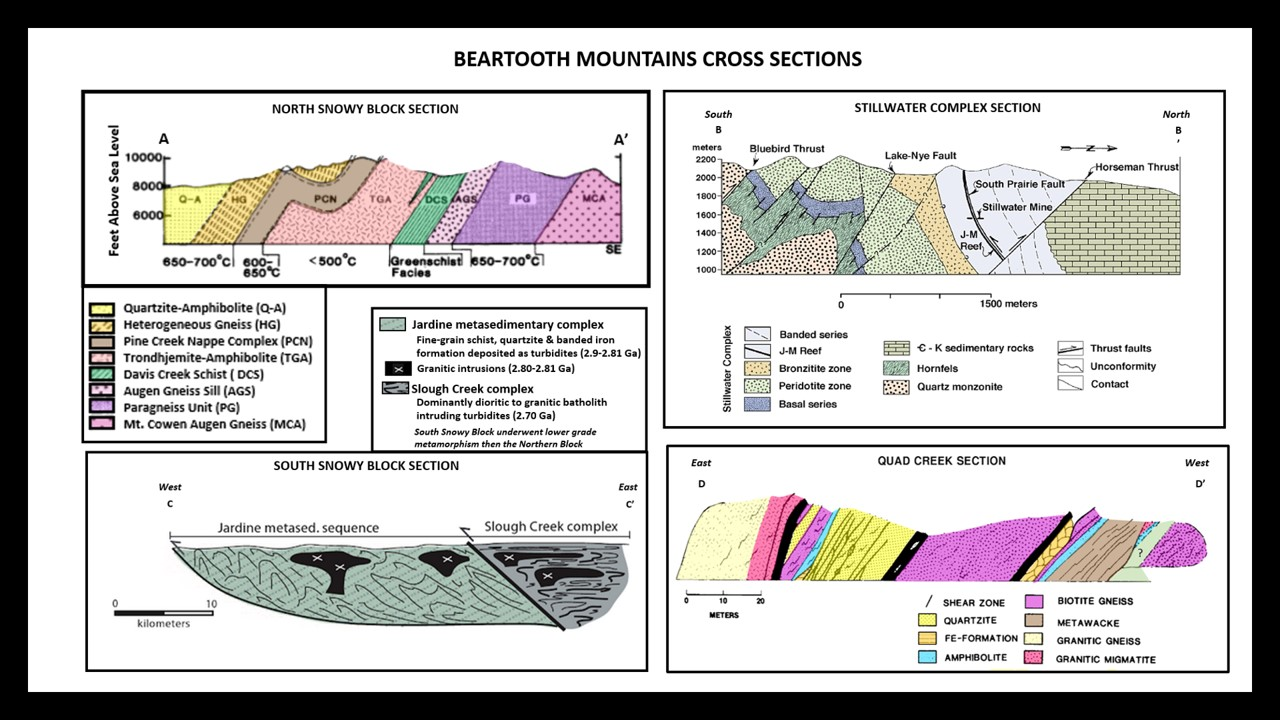

The Beartooth mountains are a northwest-southeast trending mountain uplift in Montana and Wyoming. The range is about 75 miles long and 45 miles wide with 26 peaks over 12,000 foot elevation. The rocks were uplifted during the Laramide Orogeny (65-57 million years ago). Three crustal blocks are recognized by varying lithologies and structural barriers: North Snowy Block, South Snowy Block and Beartooth Plateau Block.

The North Snowy Block is in the northwest, east of Paradise Valley. The Elbow Creek fault is on the south margin and the Mill Creek-Stillwater fault system bounds the eastern border. The block consists of seven lithologies of an Archean assemblage meta sedimentary and meta igneous allochthonous rocks (produced somewhere else). Formation contacts between the units are either structural (faulted) or intrusive surfaces. They attached with the Beartooth Plateau block about 2.55 billion years ago. The 2.7 billion year old Stillwater Complex domain along the northern margin, holds the largest deposits of platinum-palladium-rhodium (PGE – platinum group elements) and chromium in the United States. These metallic mineral deposits are contained in an Archean layered mafic intrusive igneous rocks, a Cretaceous and Tertiary volcanic-plutonic complex, and in placer deposits.

The South Snowy Block is in the southwest corner of the range. It is separated from the North Snowy Block by the Elbow Creek fault. The surface of the block is covered by Tertiary volcanics and intrusives. Basement rocks are dominated by low grade metamorphic (schists) that were deposited as turbidites in an ancient ocean basin. The eastern portion of the block is dominantly younger (~ 2.79-2.81 Ga) felsic monzonite to diorite plutons and dikes with a minor volume of higher metamorphic grade metasediments. These two areas are separated by a structural zone containing migmatite and schists. The Cooke City zone is a structural depression that separates the South Snowy Block from the main Beartooth Plateau. The lineation extends 65 miles from the confluence of Mill Creek and the Yellowstone River near Pray, Montana in the northwest to the Clarks Fork Canyon area in the southeast. Precambrian mafic dikes and fault trends have the same northwest alignment suggesting an Archean origin for this zone.

The Beartooth Plateau Block covers the eastern two thirds of the uplift. The dominate lithology is 2.7-2.54 billion year old granitic rock. The oldest rocks (3.4 Ga) are high grade metamorphosed supercrustal rocks along Quad Creek and the Hellroaring Plateau. A four billion year old zircon was discovered within a quartzite at Quad Creek that indicates the presence of an earlier granitic source for the clast. The Beartooth All American Road crosses the southeastern portion of this alpine plateau.

The North Snowy Block is in the northwest, east of Paradise Valley. The Elbow Creek fault is on the south margin and the Mill Creek-Stillwater fault system bounds the eastern border. The block consists of seven lithologies of an Archean assemblage meta sedimentary and meta igneous allochthonous rocks (produced somewhere else). Formation contacts between the units are either structural (faulted) or intrusive surfaces. They attached with the Beartooth Plateau block about 2.55 billion years ago. The 2.7 billion year old Stillwater Complex domain along the northern margin, holds the largest deposits of platinum-palladium-rhodium (PGE – platinum group elements) and chromium in the United States. These metallic mineral deposits are contained in an Archean layered mafic intrusive igneous rocks, a Cretaceous and Tertiary volcanic-plutonic complex, and in placer deposits.

The South Snowy Block is in the southwest corner of the range. It is separated from the North Snowy Block by the Elbow Creek fault. The surface of the block is covered by Tertiary volcanics and intrusives. Basement rocks are dominated by low grade metamorphic (schists) that were deposited as turbidites in an ancient ocean basin. The eastern portion of the block is dominantly younger (~ 2.79-2.81 Ga) felsic monzonite to diorite plutons and dikes with a minor volume of higher metamorphic grade metasediments. These two areas are separated by a structural zone containing migmatite and schists. The Cooke City zone is a structural depression that separates the South Snowy Block from the main Beartooth Plateau. The lineation extends 65 miles from the confluence of Mill Creek and the Yellowstone River near Pray, Montana in the northwest to the Clarks Fork Canyon area in the southeast. Precambrian mafic dikes and fault trends have the same northwest alignment suggesting an Archean origin for this zone.

The Beartooth Plateau Block covers the eastern two thirds of the uplift. The dominate lithology is 2.7-2.54 billion year old granitic rock. The oldest rocks (3.4 Ga) are high grade metamorphosed supercrustal rocks along Quad Creek and the Hellroaring Plateau. A four billion year old zircon was discovered within a quartzite at Quad Creek that indicates the presence of an earlier granitic source for the clast. The Beartooth All American Road crosses the southeastern portion of this alpine plateau.

Structural cross sections from the four rock domains of the Beartooth Mountains.

Image: AA’: After Mogk, D.W., Mueller, P.A. and Wooden, J.L., 1988, Archean Tectonics of the North Snowy Block, Beartooth Mountains, Montana: The Journal of Geology, Vol. 96, No. 2, Fig. 2 & 3, p. 127; https://www.jstor.org/stable/30066411?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents;

BB’: After Henry, D.W., Mogk, D.J. and Mueller, P., 2013,The Middle Crust of the Wyoming Province – Ground-truthing above 2000 Meters Elevation in the Beartooth Mountains, Montana and Wyoming: Earth Scope in the Northern Rockies Poster, Fig. 5; https://serc.carleton.edu/earthscoperockies/volabstracts.html;

CC’: Foster, D.A., Mueller, P.A., Goscombe, B.D. and Gray, D.R., 2013, Accreted Turbidite Fans and Remnant Ocean Basins in Phanerozoic Origins: in Dilek, Y. and Furnes, H., editors, Evolution of Archean Crust and Life, Fig. 10.15b, p. 316;

DD’: After Henry, D.J., Wooden, J.L., Mueller, P.A., Warner, J.L. and Berman, R.L., 0982, Granulite Grade Supracrustal Assemblages of the Quad Creek Area, Eastern Beartooth Mountains, Montana: in Mueller, P.A. and Wooden, J.L., Compilers, Precambrian Geology of the Beartooth Mountains, Montana and Wyoming: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 84, Fig. 2, p. 150; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Darrell_Henry/publication/233530661_Granulite_grade_supracrustal_assemblages_of_the_Quad_Creek_area_eastern_Beartooth_Mountains_Montana/links/552e79ee0cf2d495071862c8/Granulite-grade-supracrustal-assemblages-of-the-Quad-Creek-area-eastern-Beartooth-Mountains-Montana.pdf.

Image: AA’: After Mogk, D.W., Mueller, P.A. and Wooden, J.L., 1988, Archean Tectonics of the North Snowy Block, Beartooth Mountains, Montana: The Journal of Geology, Vol. 96, No. 2, Fig. 2 & 3, p. 127; https://www.jstor.org/stable/30066411?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents;

BB’: After Henry, D.W., Mogk, D.J. and Mueller, P., 2013,The Middle Crust of the Wyoming Province – Ground-truthing above 2000 Meters Elevation in the Beartooth Mountains, Montana and Wyoming: Earth Scope in the Northern Rockies Poster, Fig. 5; https://serc.carleton.edu/earthscoperockies/volabstracts.html;

CC’: Foster, D.A., Mueller, P.A., Goscombe, B.D. and Gray, D.R., 2013, Accreted Turbidite Fans and Remnant Ocean Basins in Phanerozoic Origins: in Dilek, Y. and Furnes, H., editors, Evolution of Archean Crust and Life, Fig. 10.15b, p. 316;

DD’: After Henry, D.J., Wooden, J.L., Mueller, P.A., Warner, J.L. and Berman, R.L., 0982, Granulite Grade Supracrustal Assemblages of the Quad Creek Area, Eastern Beartooth Mountains, Montana: in Mueller, P.A. and Wooden, J.L., Compilers, Precambrian Geology of the Beartooth Mountains, Montana and Wyoming: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 84, Fig. 2, p. 150; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Darrell_Henry/publication/233530661_Granulite_grade_supracrustal_assemblages_of_the_Quad_Creek_area_eastern_Beartooth_Mountains_Montana/links/552e79ee0cf2d495071862c8/Granulite-grade-supracrustal-assemblages-of-the-Quad-Creek-area-eastern-Beartooth-Mountains-Montana.pdf.

The geologic history of the Beartooth Mountains begins sometime near 4 billion years ago. A cratonic source shed sediments into an adjacent sea. Zircons are generally produced by granitic terrains and contain uranium 238 that can be used in radiometric dating of the host rocks. The zircons discovered on the Beartooth Plateau record at least three major episodes of crustal development between 4.0 and 3.4 billion years ago. These ancient rocks were eroded and deposited in the bordering seaway. The buried sedimentary units were crystallized and metamorphized between 3.0 and 2.5 billion years ago into gneisses and granite of the Beartooth Plateau. The Long Lake granodiorite intruded these rocks between 2.9 and 2.7 billion years ago. Northwest trending mafic intrusions occurred in several stages between 2.8 billion and 780 million years ago. The latter stages are due to extension during the breakup of the super continent Rodinia. The Stillwater complex was emplaced along the northwest margin 2.7 billion years ago.

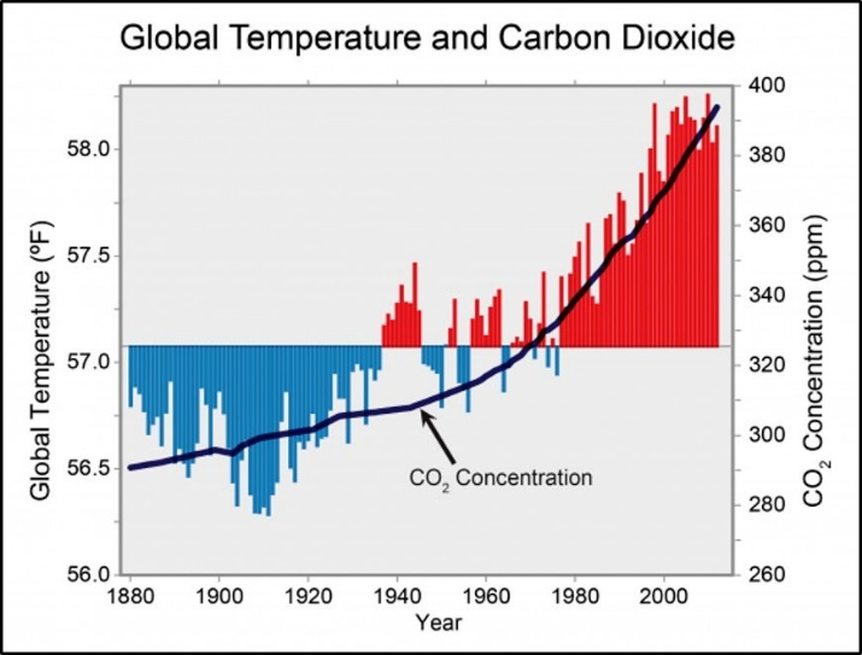

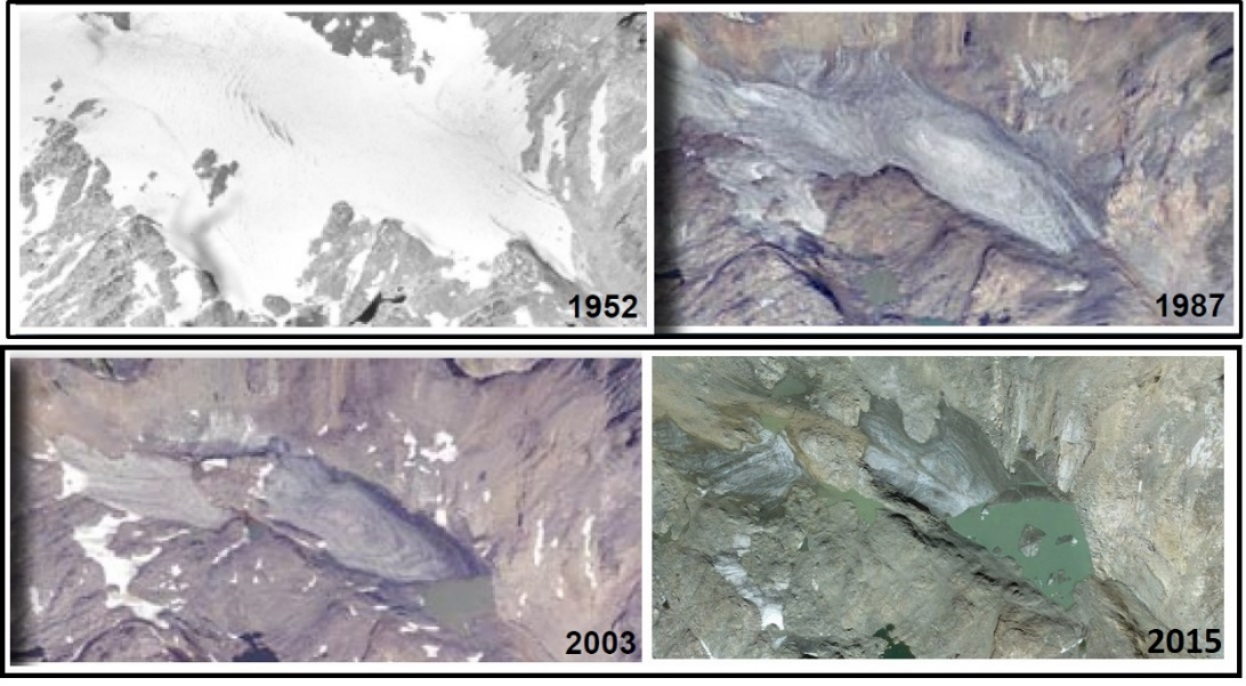

The region was tectonically quiet for about 2 billion years. Phanerozoic (Paleozoic to Late Cretaceous) sediments were deposited across the eroded, nearly flat igneous and metamorphic basement terrain beginning about 530 million years ago. The time gap here represents the great unconformity. The Laramide Orogeny elevated the Beartooth Mountains block between 65 and 57 million years ago. The compression forces causing tectonism was subduction along the western margin of North America. The Phanerozoic sedimentary cover was almost completely eroded during the next 20 million years. By The late Oligocene early Miocene, the basins were filled with clastic sediments eroded from the mountains. The mountains record this fill level with the sub-summit erosion surface (10,000 to 11,000 foot elevation). Beartooth and Clay Buttes are remnants of the sedimentary cover on the mountains. Eocene volcanism (53-43 million years ago) began near the end of Laramide structuring producing two eruptive trends. The eastern trend closely follows the Cooke City Zone suggesting magma reached the surface along Precambrian faults and fractures. Glacial ice sculpted the landscape over the last 2 million years. Today human activity has become a geologic factor in shaping the Earth’s atmosphere. Ten giga tons of carbon are released to the atmosphere every year. There has been a marked climate change beginning with the late 18th to early 19th century Industrial Revolution and glacial ice has been melting in the Beartooth Mountains.

The region was tectonically quiet for about 2 billion years. Phanerozoic (Paleozoic to Late Cretaceous) sediments were deposited across the eroded, nearly flat igneous and metamorphic basement terrain beginning about 530 million years ago. The time gap here represents the great unconformity. The Laramide Orogeny elevated the Beartooth Mountains block between 65 and 57 million years ago. The compression forces causing tectonism was subduction along the western margin of North America. The Phanerozoic sedimentary cover was almost completely eroded during the next 20 million years. By The late Oligocene early Miocene, the basins were filled with clastic sediments eroded from the mountains. The mountains record this fill level with the sub-summit erosion surface (10,000 to 11,000 foot elevation). Beartooth and Clay Buttes are remnants of the sedimentary cover on the mountains. Eocene volcanism (53-43 million years ago) began near the end of Laramide structuring producing two eruptive trends. The eastern trend closely follows the Cooke City Zone suggesting magma reached the surface along Precambrian faults and fractures. Glacial ice sculpted the landscape over the last 2 million years. Today human activity has become a geologic factor in shaping the Earth’s atmosphere. Ten giga tons of carbon are released to the atmosphere every year. There has been a marked climate change beginning with the late 18th to early 19th century Industrial Revolution and glacial ice has been melting in the Beartooth Mountains.

Global annual average temperature (as measured over both land and oceans) has increased by more than 1.5°F (0.8°C) since 1880 (through 2012). Red bars show temperatures above the long-term average, and blue bars indicate temperatures below the long-term average. The black line shows atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in parts per million (ppm).

While there is a clear long-term global warming trend, some years do not show a temperature increase relative to the previous year, and some years show greater changes than others. These year-to-year fluctuations in temperature are due to natural processes, such as the effects of El Niños, La Niñas, and volcanic eruptions.

Image: https://www.globalchange.gov/browse/multimedia/global-temperature-and-carbon-dioxide.

While there is a clear long-term global warming trend, some years do not show a temperature increase relative to the previous year, and some years show greater changes than others. These year-to-year fluctuations in temperature are due to natural processes, such as the effects of El Niños, La Niñas, and volcanic eruptions.

Image: https://www.globalchange.gov/browse/multimedia/global-temperature-and-carbon-dioxide.

Images of the rapid retreat of the largest ice mass in the Beartooth Mountains, Castle Rocks glacier over the last six decades. Glaciers are melting and disappearing throughout the Rocky Mountains.

Image: https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprd3834828.pdf.

Image: https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprd3834828.pdf.

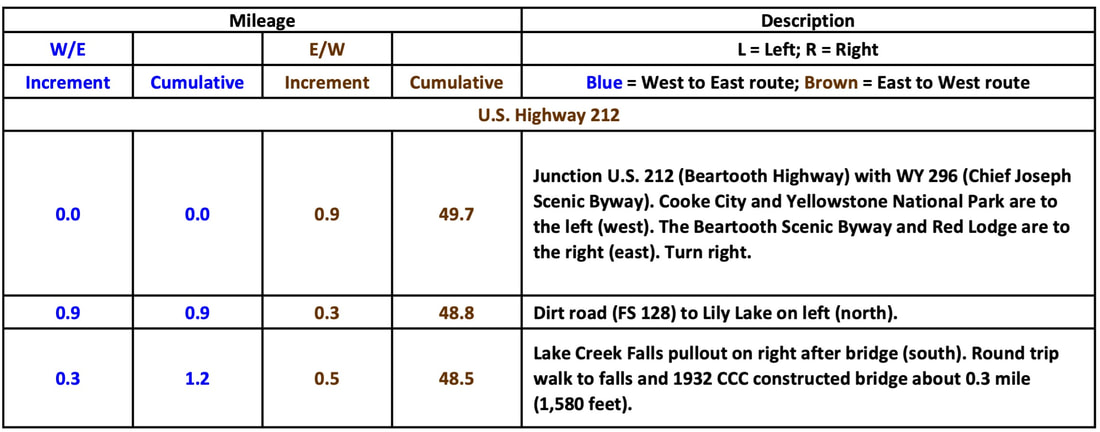

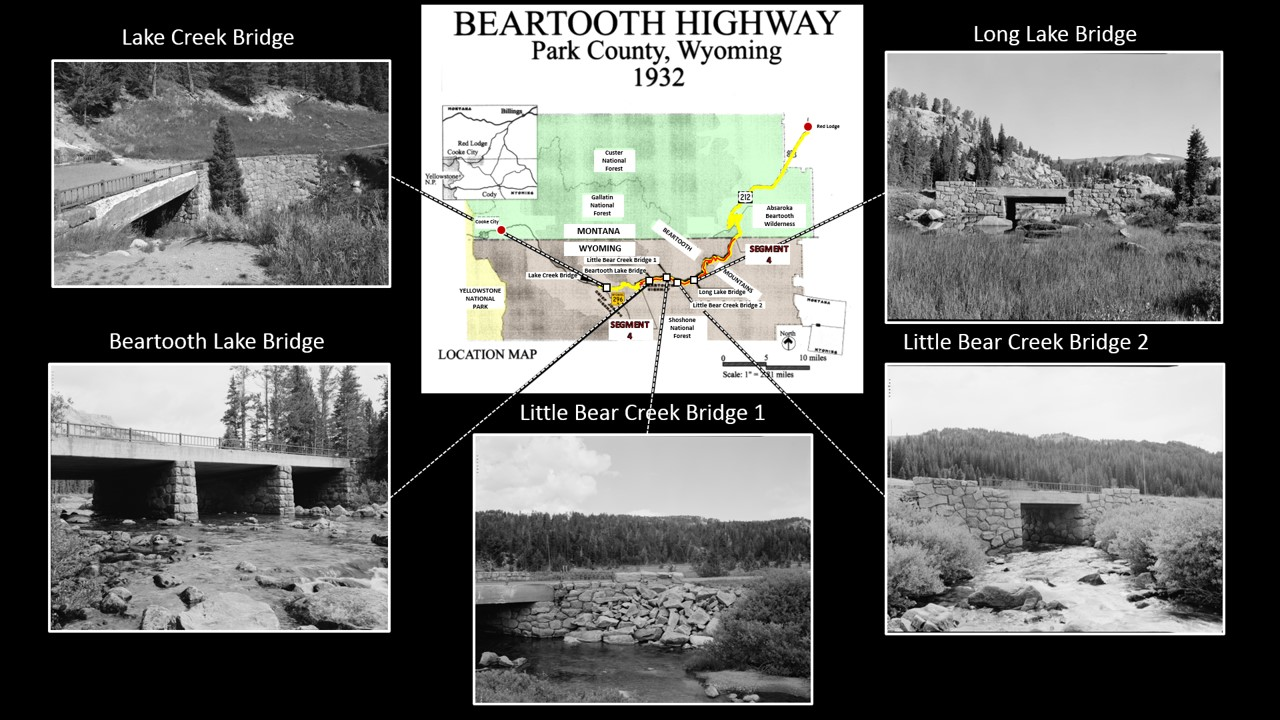

Lake Creek Falls (Elevation 7,329’) plummets 35 feet through a narrow gorge cut in Precambrian granite. The bridge that serves as a pedestrian walkway was part of the original Beartooth Highway. It is one of five bridges preserved from the original construction. The abutments on these bridges were hand chiseled and fitted by the depression Civilian Conservation Corps. The current steel bridge was constructed downstream in 1974 to accommodate modern vehicles.

Lake Creek Falls and Bridge.

Image: After https://www.world-of-waterfalls.com/userwaterfallreviews/lake-creek-falls-beartooth-highway-montana/ and https://bridgehunter.com/wy/park/lake-creek/.

Image: After https://www.world-of-waterfalls.com/userwaterfallreviews/lake-creek-falls-beartooth-highway-montana/ and https://bridgehunter.com/wy/park/lake-creek/.

Preserved bridges of the original Beartooth Highway.

Image: After Library of Congress Historic American Buildings Survey, Engineering Record, Landscapes Survey Photos HAER No. A-D, and https://bridgehunter.com/photos/30/22/302263-L.jpg.

Image: After Library of Congress Historic American Buildings Survey, Engineering Record, Landscapes Survey Photos HAER No. A-D, and https://bridgehunter.com/photos/30/22/302263-L.jpg.

Clarks Fork Valley overlook. The treed area in the foreground is underlain by Precambrian granitic rocks. The Clarks Fork Valley is the flat area beyond the trees. The Clarks Fork River carves a canyon between the Beartooth granitic and the Absaroka Mountains volcanic terrains. The high ground beyond the valley has blocks of Paleozoic and volcanic rocks that were displaced by the Heart Mountain Detachment (HMD). Motion on the Heart Mountain blocks above the red line was from right to left in the image.

Image: After U.S. Forest Service, 1988, https://nara.getarchive.net/media/beartooth-highway-view-from-clarks-fork-overlook-85594a?zoom=true.

Image: After U.S. Forest Service, 1988, https://nara.getarchive.net/media/beartooth-highway-view-from-clarks-fork-overlook-85594a?zoom=true.

The Clarks Fork Overlook view to the south shows the forest covered Precambrian basement within the Cooke City structural zone, the Clarks Fork alluvial valley, and displaced Heart Mountain blocks above the horizontal bedding plane portion of the Heart Mountain Detachment fault (HMD). Eocene dikes, lacking roots below the HMD fault, intrude the Madison Limestone. No roots below the HMD fault is evidence that the dikes were transported with the Paleozoic HMD blocks. For more on the Heart Mountain Fault see https://www.geowyo.com/heart-mountain.html and https://www.geowyo.com/sunlight-basin.html.

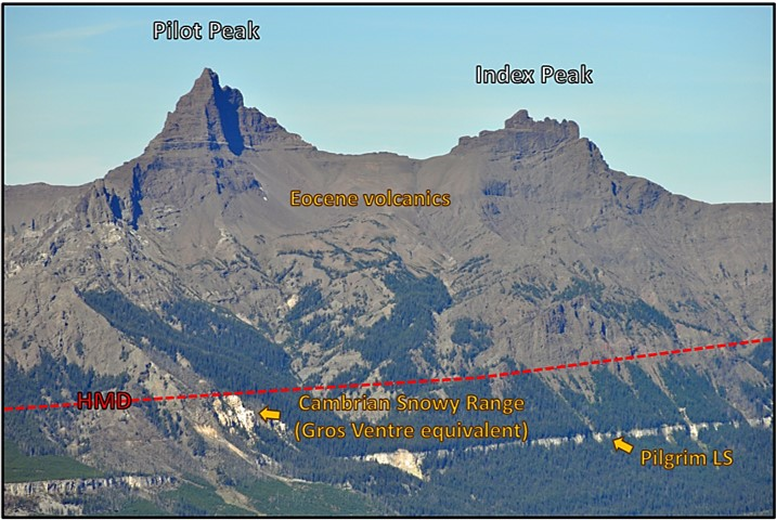

These two peaks are composed of Absaroka volcanic rock that were transported by the Heart Mountain Detachment that occurred 48.9 million years ago. The displaced rocks are in fault contact with lower Paleozoic rocks in the footwall beneath the detachment. Movement was to the south-southeast toward Dead Indian Hill. Glacial ice sculpted the peaks within the last 2 million years.

Close image of Pilot and Index Peak. The Heart Mountain Detachment (HMD) is shown by the red dashed line. Displace rocks lie above and in-place rocks are below the line.

Image: After Cline, M., 2015, Pilot and Index Peaks, Park County Wyoming, Absaroka Range; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/Pilot_and_Index_Peaks_Wyoming.jpg.

Image: After Cline, M., 2015, Pilot and Index Peaks, Park County Wyoming, Absaroka Range; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/Pilot_and_Index_Peaks_Wyoming.jpg.

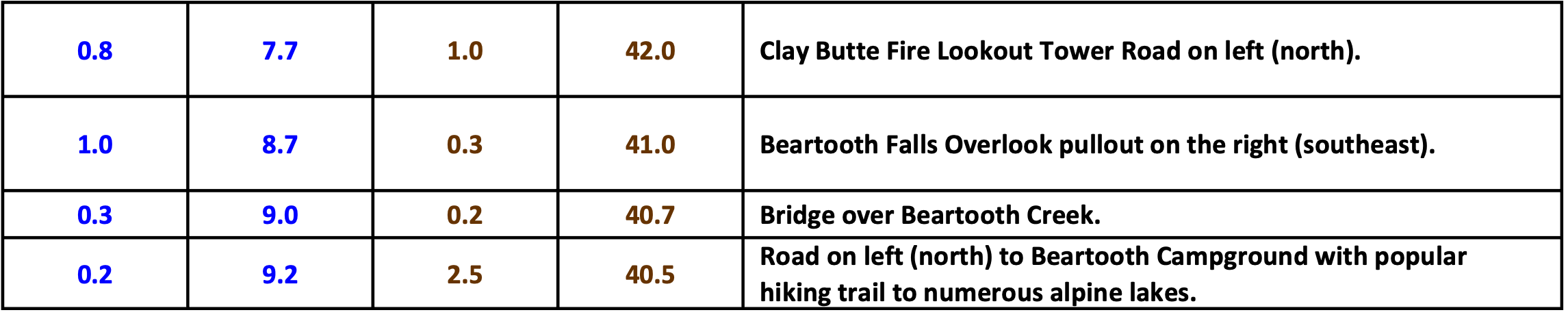

Clay Butte, along with Beartooth Butte, are remnants of the sedimentary rocks that covered the Beartooth Plateau before erosion. The tower atop the butte was a fire lookout station for the Shoshone National Forest built in 1942 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was in operation until 1960 when the Forest Service began to use aircraft for fire reporting. Look at the outside walls of the Clay Butte Tower for “leopard rock”, an attractive Precambrian igneous rock with large white plagioclase crystals in a dark gray, fine-grain mafic groundmass that gives the rock a leopard fur appearance. Outcrops of leopard rock occur along the west side of Clay Butte Creek slightly upstream from its crossing of the Beartooth Highway. The creek crosses the Beartooth Highway about four tenths of mile east of the turnoff for Clay Butte Tower.

Clay Butte Tower and Beartooth Falls. Geologic map and cross Section AA’ show the remnant sedimentary rocks preserved in this area. Clay Butte is an interpretive center that has magnificent views of the landscape.

Image: (Tower) National Park Service; (Pullout) Google Earth; (Map & cross section) After Pierce, W.G. and Nelson, W.H., 1971, Geologic map of the Beartooth Butte quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey 935; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_2235.htm; and (Falls) Beartoothhighway.com.

Image: (Tower) National Park Service; (Pullout) Google Earth; (Map & cross section) After Pierce, W.G. and Nelson, W.H., 1971, Geologic map of the Beartooth Butte quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey 935; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_2235.htm; and (Falls) Beartoothhighway.com.

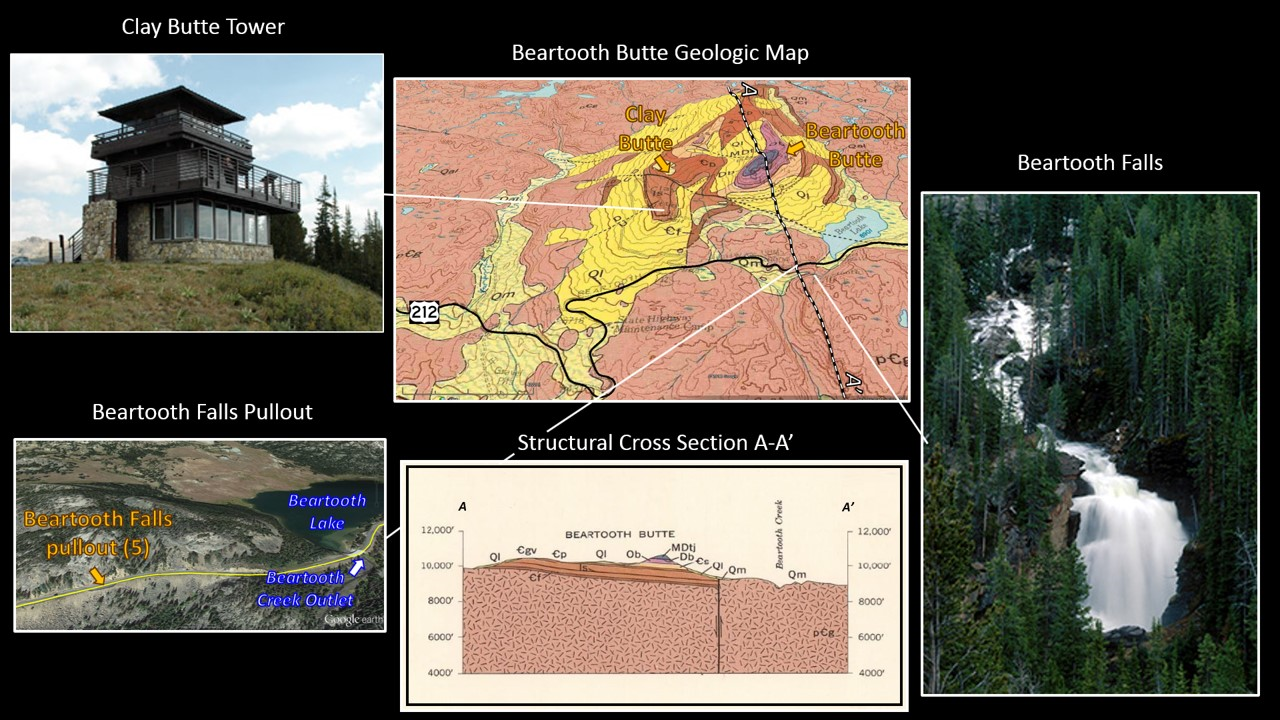

Top of the World Store was built at Beartooth Lake in 1948. The store was moved to its present location in 1966. It provides supplies to campers, backpackers and motorists. Beartooth Butte is to the west of the store on the west shore of the Beartooth Lake. The sedimentary rocks here are a preserved remnant of the former Phanerozoic cover. This is the type location of the Beartooth Butte Formation first reported in 1934. The formation is a red channel fill at the base of the Jefferson Dolomite. Rare fossil fish were uncovered in this 411 to 408 million year old estuarine channel.

Left: West face of Beartooth Butte. Geologic abbreviations: Qls, Quaternary landslide, Dj, Devonian Jefferson Dolomite, Db, Devonian Beartooth Butte Formation, Ob, Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite, Cs, Cambrian Snowy Range Formation, Cp, Cambrian Pilgrim Limestone, Cpk, Cambrian Park Shale. Right: Top of the World Store.

Image: Butte: After Lumley, T, 2015, Beartooth Butte; https://www.flickr.com/photos/tim_lumley/25084625791; Store: After Bredeson, L., No Date, Top of the World Store on the Beartooth Highway

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/188166090650729029/.

Image: Butte: After Lumley, T, 2015, Beartooth Butte; https://www.flickr.com/photos/tim_lumley/25084625791; Store: After Bredeson, L., No Date, Top of the World Store on the Beartooth Highway

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/188166090650729029/.

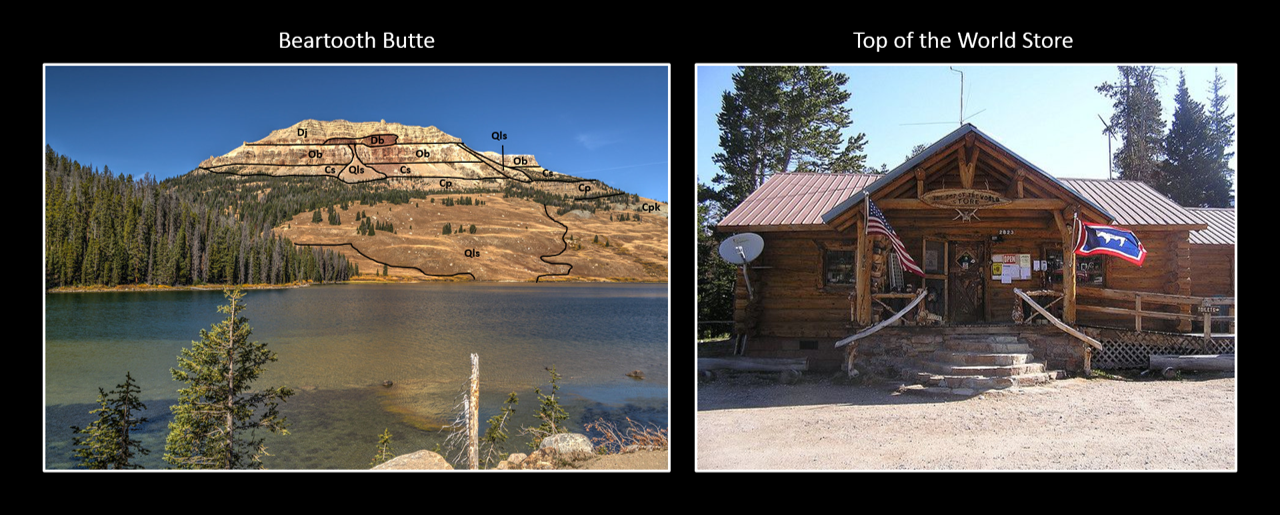

Road is now traveling on a highly glaciated alpine Precambrian surface. Ice carved geomorphic features include paternoster lakes (series of glacial lakes connect by a stream), roche moutonnee (glacial shaped rock outcrop with upstream smooth and downstream rough), erratics (glacial transported rock fragment), rock glaciers (rock, ice, snow and mud moving downhill by gravity) and patterned ground (geometric pattern of rocks formed by frost heaving in periglacial areas).

Beartooth Mountains glacial features. Cross section AA’ shows the Red Lodge terraces. Note the relative elevations of Rock and Bear Creeks. Headward erosion of Bear Creek will eventually capture Rock Creek and divert its flow. Location of two of three glaciers with frozen remains of the Rocky Mountain Locust. The insect swarms were believed to be trapped by early storms and frozen in their icy graveyard (see Geowyo Grasshopper Glacier) shown by blue outlined white stars. The largest glacier in the Beartooth Mountains, Castle Rock Glacier, is shown by a brown outlined gold star.

Image: Google Earth with data from Mueller, P.A., Locke, W.W., and Wooden, J.L., 1987, A Study in Contrasts: Archean and Quaternary Geology of the Beartooth Highway, Montana and Wyoming, in Beus, S.S., ed., Centennial Field Guide Volume 2: Rocky Mountain Section of the Geological Society of America, Fig. 1, p. 75-78.

Image: Google Earth with data from Mueller, P.A., Locke, W.W., and Wooden, J.L., 1987, A Study in Contrasts: Archean and Quaternary Geology of the Beartooth Highway, Montana and Wyoming, in Beus, S.S., ed., Centennial Field Guide Volume 2: Rocky Mountain Section of the Geological Society of America, Fig. 1, p. 75-78.

The Quaternary ice cap covered the southeast region of the Beartooth Plateau. The basement rocks are scraped nearly flat. Cirques scallop the rocks and were sites that added ice to troughs developed in the valleys. Intersecting fracture/joint trends were weakness zones developed in the Precambrian and during the Laramide structuring. The ice exploited these zones leaving a series of lakes along these trends. The lakes appear as beads on a rosary and are called paternoster lakes.

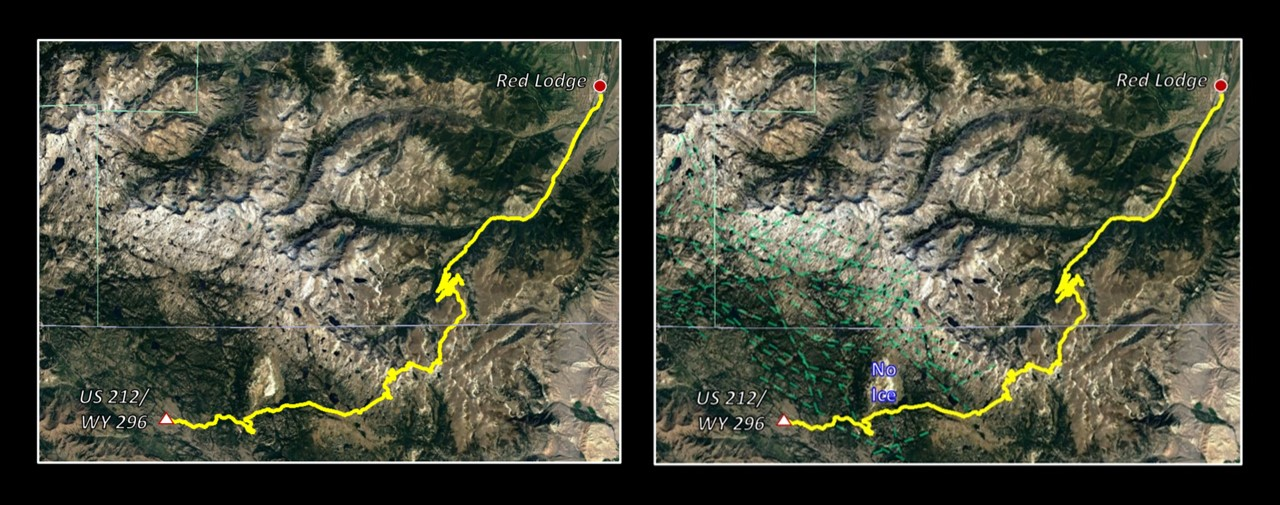

Beartooth Plateau lakes developed along fracture lineaments in glacial plucked depressions. Fractures trends beneath the ice cap shown by green dashed lines. Beartooth and Clay Buttes (labeled No Ice) projected above the surrounding ice sheet. Such a rock surface is called a nunatack after the Inuit word “nunataq.”

Image: After Google Earth

Image: After Google Earth

Morrison Jeep Trail (USFS Road 120) from U.S. 212 to Clarks Fork Canyon and image of the switchbacks from Dillworth Bench.

Image: Google Earth and https://www.dangerousroads.org/north-america/usa/6968-morrison-jeep-trail.html.

Image: Google Earth and https://www.dangerousroads.org/north-america/usa/6968-morrison-jeep-trail.html.

The Morison Jeep Trail is a 22 mile rough, single lane track with 5,700 feet of elevation relief. It has 27 tight dangerous switchbacks that descend from Dillworth Bench to the Clarks Fork Canyon. It is a route that should be driven only by experts with well-maintained ORVs and spare tires.

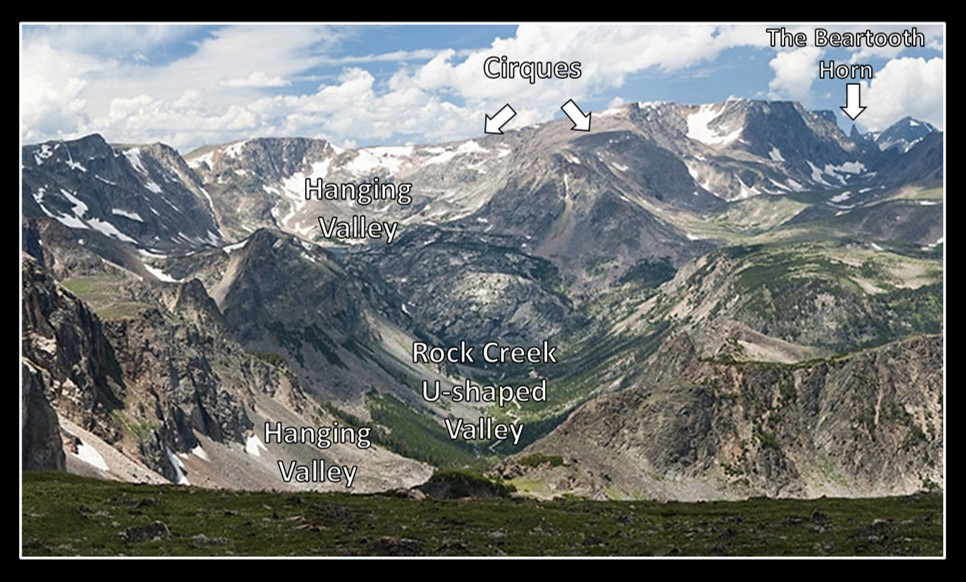

The West Summit provides views of patterned ground, multiple lakes, cirques, glaciated valleys and the Beartooth horn for which the mountains are named.

West Summit Overlook Left: patterned ground; Right: Daphnia Lake to the southeast, one of the hundreds of lakes on the Beartooth Mountains. Beartooth Pass lies on the ridge between Mirror Lake (northwest) and Gardiner Lake (southeast) cirques.

Image: Yakovlev, O., 2007, Geology Field Trip, IMG_2855 & 2859.

Image: Yakovlev, O., 2007, Geology Field Trip, IMG_2855 & 2859.

The Bears Tooth horn and glacial features from Beartooth Pass area.

Image: After https://www.yellowstonepark.com/road-trips/beartooth-highway-scenic-drive.

Image: After https://www.yellowstonepark.com/road-trips/beartooth-highway-scenic-drive.

Gardiner Lake Overlook of cirque. The Gardiner Headwall is just off the right side of picture.

Image: After Olga, M., No Date, Royalty-free stock photo ID: 764709928; https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/panorama-gardner-lake-beartooth-pass-peaks-764709928.

Image: After Olga, M., No Date, Royalty-free stock photo ID: 764709928; https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/panorama-gardner-lake-beartooth-pass-peaks-764709928.

Gardiner Lake Trail is a 1.6 mile roundtrip hike to the south end of the lake. The trail begins at 10,550 foot elevation and descends 650 feet. The southeast outlet stream is one of the headwaters of Littlerock Creek that empties into the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River near Clark, Wyoming.

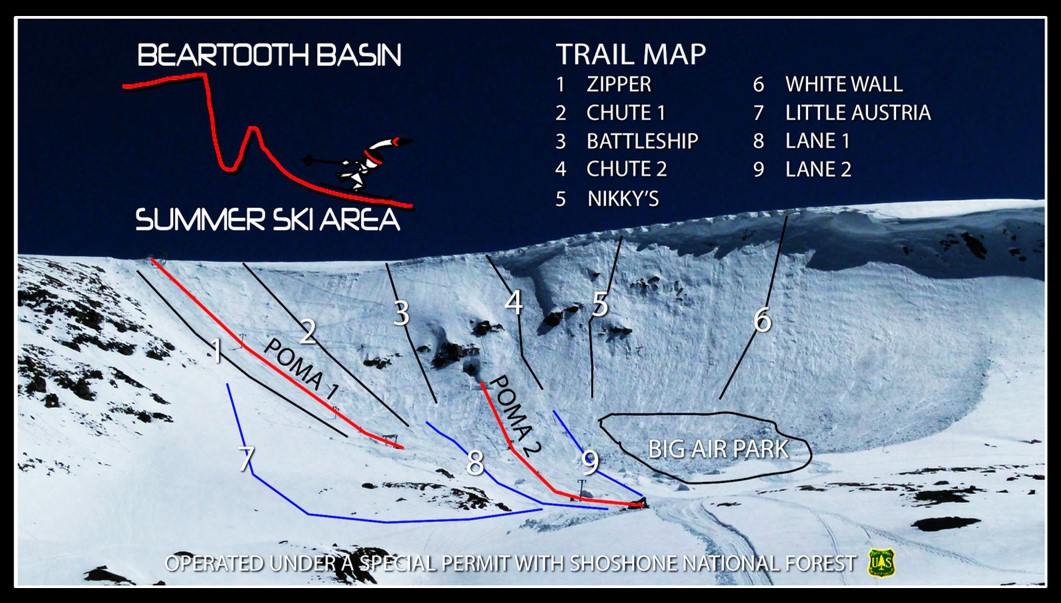

The Beartooth Basin ski area is on the Twin Lakes cirque headwall. The ski season starts after the highway opens on the Memorial Day weekend and ends in early July, snow and weather permitting. POMA tow 1 is located a tenth of a mile north of the pullout, on the Twin Lakes south cirque headwall. It is the steepest POMA you will probably ever ride. The second POMA tow serves the lower part of the slope.

Locals checking out POMA 1 operation.

Image: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bk7_IlRgmwq/

Image: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bk7_IlRgmwq/

Beartooth Basin ski trail map.

Image: https://beartoothbasin.com/map

Image: https://beartoothbasin.com/map

Skier cornice drop to a 50 degree slope at Beartooth Basin.

Image: https://beartoothbasin.com/media.

Image: https://beartoothbasin.com/media.

View to south of Twin Lakes in late July.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

Wyoming and Montana border sign.

Image: Left: https://timvp.com/2014/071814.html; Right: https://www.omnibus-mi.us/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BP20130725x04403.jpg.

Image: Left: https://timvp.com/2014/071814.html; Right: https://www.omnibus-mi.us/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BP20130725x04403.jpg.

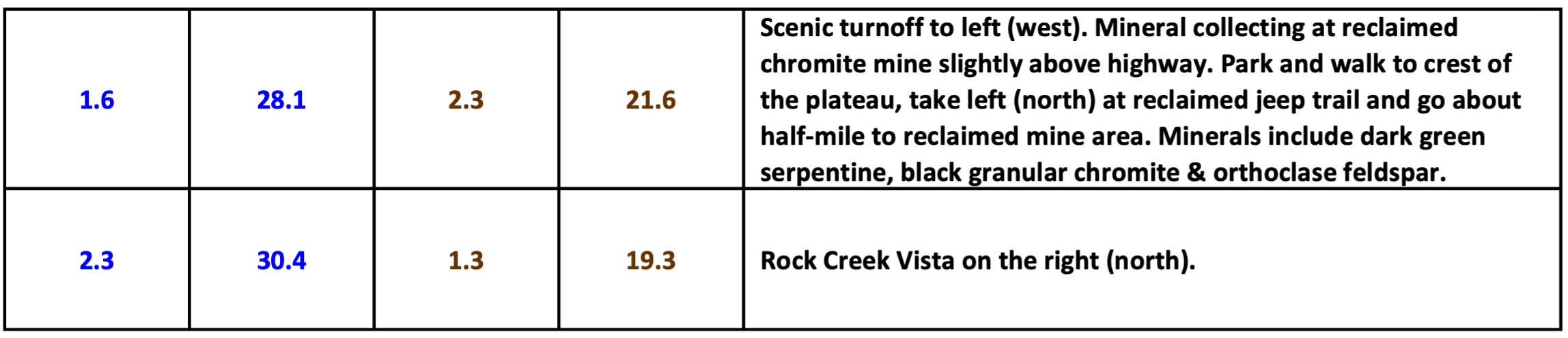

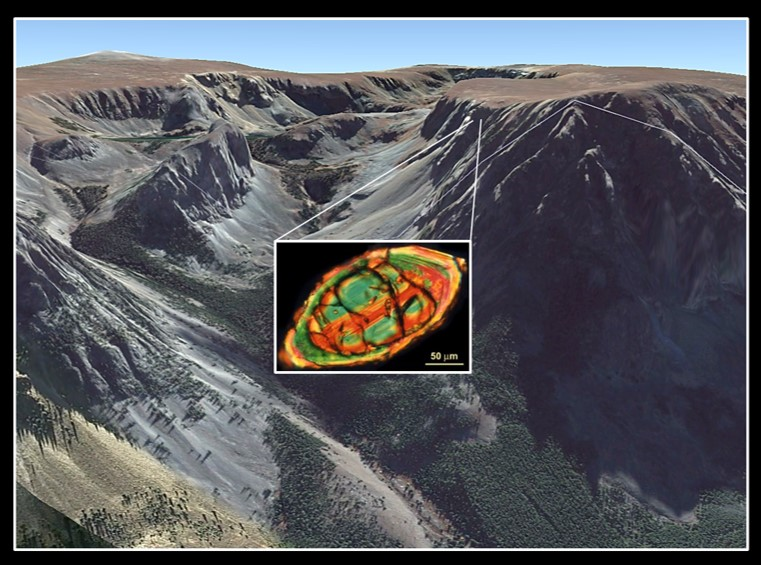

View of Rock Creek, Line Creek Plateau and Hellroaring Plateau during the 1940’s. Chromite was mined during World War II at location No 1, the Highline Claims. The open pit chromite mine and access roads have since been reclaimed. Numbers on Hellroaring Plateau are chromite locations.

Image by James, H.L., 1946, Chromite deposits near Red Lodge, Carbon County, Montana, US Geological Survey Bulletin 945-F. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/b945F

Image by James, H.L., 1946, Chromite deposits near Red Lodge, Carbon County, Montana, US Geological Survey Bulletin 945-F. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/b945F

Rock Creek Vista gives a closeup view of the plateau granitic rocks and a majestic view of a glacial carved canyon with hanging valleys.

Southwest view of Rock Creek from Vista Point

Image: Canon, M., 2014, https://www.google.com/maps/uv?hl=en&pb=!1s0x534edc67c304776b%3A0x48e022023bbe0bff!2m22!2m2!1i80!2i80!3m1!2i20!16m16!1b1!2m2!1m1!1e1!2m2!1m1!1e3!2m2!1m1!1e5!2m2!1m1!1e4!2m2!1m1!1e6!3m1!7e115!4shttps%3A%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipO1Efe2vyhn05txbzUfQZ3GPtsteKmMXcaTiVku%3Dw213-h160-k-no!5srock%20creek%20vista%20mt%20outcrop%20-%20Google%20Search!15sCAQ&imagekey=!1e10!2sAF1QipOESYm9Swp90oTgAWnL-hxO4Gthwq2Z0ElScWkY&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi4rN2w09jjAhUCTKwKHSyLBAUQoiowGXoECA4QBg.

Image: Canon, M., 2014, https://www.google.com/maps/uv?hl=en&pb=!1s0x534edc67c304776b%3A0x48e022023bbe0bff!2m22!2m2!1i80!2i80!3m1!2i20!16m16!1b1!2m2!1m1!1e1!2m2!1m1!1e3!2m2!1m1!1e5!2m2!1m1!1e4!2m2!1m1!1e6!3m1!7e115!4shttps%3A%2F%2Flh5.googleusercontent.com%2Fp%2FAF1QipO1Efe2vyhn05txbzUfQZ3GPtsteKmMXcaTiVku%3Dw213-h160-k-no!5srock%20creek%20vista%20mt%20outcrop%20-%20Google%20Search!15sCAQ&imagekey=!1e10!2sAF1QipOESYm9Swp90oTgAWnL-hxO4Gthwq2Z0ElScWkY&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi4rN2w09jjAhUCTKwKHSyLBAUQoiowGXoECA4QBg.

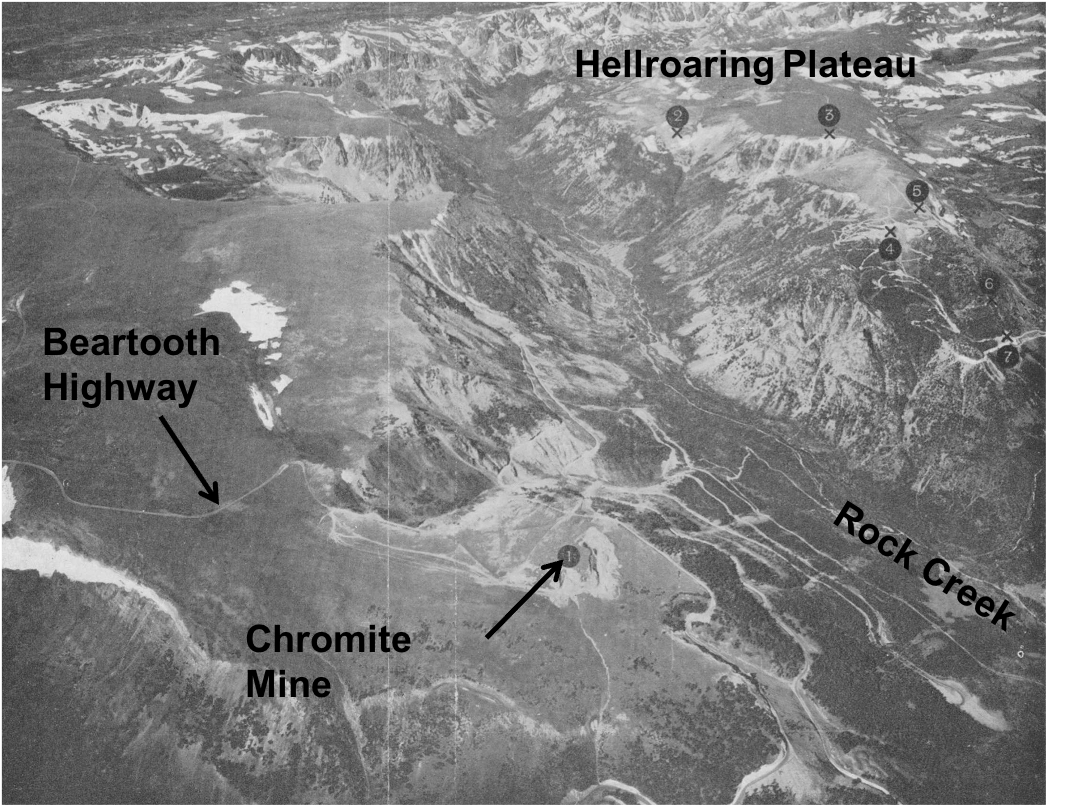

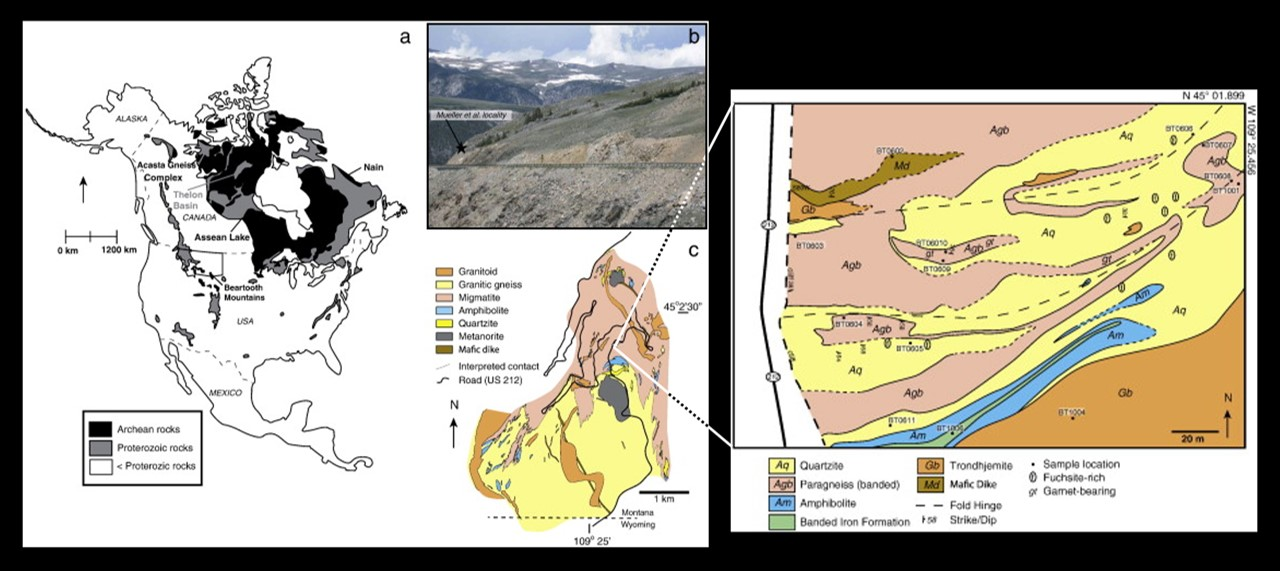

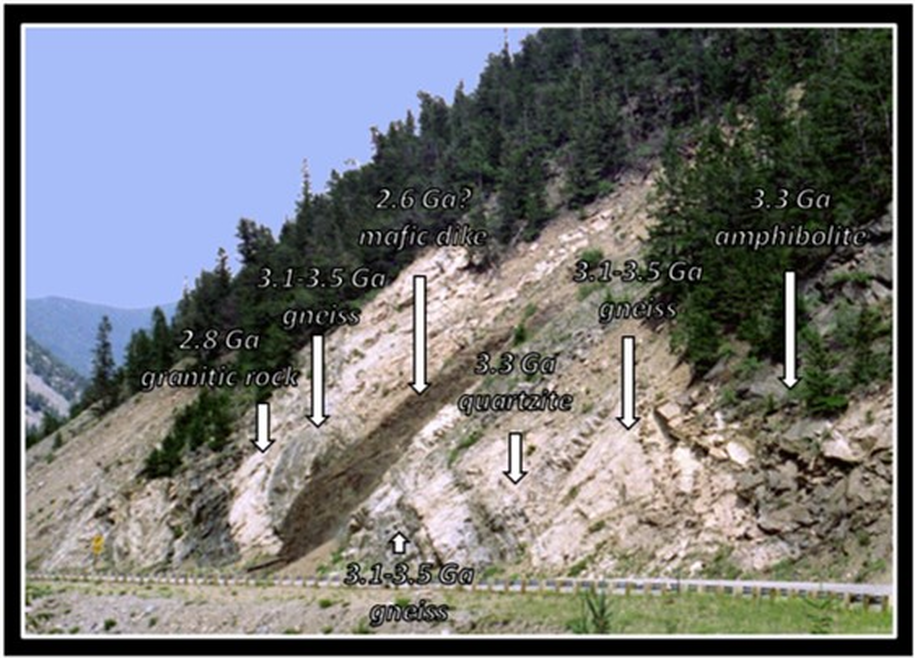

The Archean age meta-supracrustal rocks (sedimentary and igneous rock deposited on the Earth’s surface) exposed in the outcrop contain detrital zircons dated from about 4 billion years ago. There are only two other places in the world where pre-3.9 billion year old (Hadean) zircons are found, Western Australia and Northern Canada. They are a record of some of the first rock crystallized on the planet. The oldest known rock are found in meteorites (about 4.5 billion years) and on the moon (about 4.4 billion years). The 3.3 billion year old quartzitic Quad Creek host rocks were deposited in a sedimentary ocean basin next to an ancient primordial granitic source terrane that supplied the 4 billion year old zircon crystal. The rocks were buried 12.5 miles, underwent high-grade metamorphism (granulite facies), and then uplifted by the Laramide Orogeny 65 to 57 million years ago.

Quad Creek outcrop. Haden zircon sample location is a roadcut on southern side of Beartooth Highway, immediately west of Quad Creek, between milepost 50 and milepost 51, southern side of Rock Creek Canyon, just north of the eroded edge of Beartooth Plateau (coordinates: 45° 01' 41.27" North & 109° 24' 55.31" West).

Image: After Maier, A.C., , N.L., Trail, D., and Mojzsis, S.J., 2012, Geology, age and field relations of Hadean zircon-bearing supracrustal rocks from Quad Creek, eastern Beartooth Mountains (Montana and Wyoming, USA): Chemical Geology, Vol. 312-313, Fig. 1, p. 48, & Fig. 3, p. 50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0009254112001714#!

Image: After Maier, A.C., , N.L., Trail, D., and Mojzsis, S.J., 2012, Geology, age and field relations of Hadean zircon-bearing supracrustal rocks from Quad Creek, eastern Beartooth Mountains (Montana and Wyoming, USA): Chemical Geology, Vol. 312-313, Fig. 1, p. 48, & Fig. 3, p. 50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0009254112001714#!

Detrital zircons in Beartooth Mountains are dated 4.0-3.0 billion years old. These minerals suggest a Hadean to early Archean granitic source terrane.

Image: After Mogk, D.W., Mueller, P.A., Wooden, J.L., and Henry, D.J., 2019, TTGs We Have Known and Loved: 1.5 Ga of Growth and Recycling of Archean Continental Crust in the Northern Wyoming Craton )NWC): 2019 EarthScope workshop presentation; https://www.slideshare.net/sercuser/mogk-es-2019pptx.

Image: After Mogk, D.W., Mueller, P.A., Wooden, J.L., and Henry, D.J., 2019, TTGs We Have Known and Loved: 1.5 Ga of Growth and Recycling of Archean Continental Crust in the Northern Wyoming Craton )NWC): 2019 EarthScope workshop presentation; https://www.slideshare.net/sercuser/mogk-es-2019pptx.

Quad Creek outcrop with Hadean age (> 3.9 billion years) zircons in the quartzite.

Image: https://beartoothtravelguide.weebly.com/quad-creek.html.

Image: https://beartoothtravelguide.weebly.com/quad-creek.html.

Red Lodge began as a stage stop in 1884. With the discovery coal, it boomed as a mining district in the 1890s to the 1920s. The opening of the Beartooth Highway in 1936 transformed the town into a tourist center. The number one favorite stop in Red Lodge is the Montana Candy Emporium on Broadway Avenue. Here you will find candies from your youth.

Montana Candy Emporium, Red Lodge.

Image: Left: https://i.pinimg.com/236x/ea/15/e5/ea15e59bec9fe020948ce3fdf0fc7a50--red-lodge-montana-homemade-fudge.jpg; Right: https://www.facebook.com/Montana-Candy-Emporium-146508455378833/.

Image: Left: https://i.pinimg.com/236x/ea/15/e5/ea15e59bec9fe020948ce3fdf0fc7a50--red-lodge-montana-homemade-fudge.jpg; Right: https://www.facebook.com/Montana-Candy-Emporium-146508455378833/.

Geology Maps of the Beartooth Mountains

Geologic Map of Red Lodge Quadrangle that covers northeast Beartooth Mountains from Silver Gate to Red Lodge and north, by Lopez, D.A., 2001, Preliminary Geologic Map of the Red Lodge 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 423; scale 1:100,000; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/redLodge.pdf

Geologic Map of Gardiner Quadrangle that covers western Beartooth Mountains from Gardiner to the northeast gate of Yellowstone and north, by Berg, R.B., Lonn, J.D., and Locke, W.W., 1999, Geologic map of the Gardiner 30’ X 60’ quadrangle, South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 387, scale 1:100,000; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/gardiner.pdf

Geologic Map of Livingston Quadrangle that covers the northwest Beartooth Mountains southeast of Livingston, by Berg, R.B., Lopez, D.A., and Lonn, J.D., 2000, Geologic Map of the Livingston 30’ X 60’ Quadrangle, South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 406, scale 1:100,000; http://mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/livingston.pdf

Geologic Map of Cody Quadrangle that covers southeast edge of Beartooth Mountains by Pierce, W.G., 1997, Geologic map of the Cody 1 degree X 2 degree quadrangle, northwestern Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey, Miscellaneous Geologic Investigations Map I-2500, scale 1:250,000; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ngm-bin/pdp/zui_viewer.pl?id=1337.

Geologic Map of Deep Lake Quadrangle that covers southeast edge of Beartooth Mountains near Clarks Fork Canyon, by Pierce, W.G., 1965, Geologic Map of the Deep Lake Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey GQ-478, scale 1:62,500;https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_13113.htm

Geologic Map of the Beartooth Butte Quadrangle that covers the southern part of Beartooth Mountains, by Pierce, W.G., and Nelson, W.H., 1971, Geologic Map of Beartooth Butte Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey GQ-935, scale 1:62,500;https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_2235.htm

Geologic Map of Pilot Peak Quadrangle that covers south edge of Beartooth Mountains near Cooke City, by Pierce, W.G, Nelson, W.H. and Prostka, H.J., 1973, Geologic Map of the Pilot Peak Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Geologic Investigations Map I-816; scale 1:62,500; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_13015.htm

Geologic Map of Gardiner Quadrangle that covers western Beartooth Mountains from Gardiner to the northeast gate of Yellowstone and north, by Berg, R.B., Lonn, J.D., and Locke, W.W., 1999, Geologic map of the Gardiner 30’ X 60’ quadrangle, South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 387, scale 1:100,000; http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/gardiner.pdf

Geologic Map of Livingston Quadrangle that covers the northwest Beartooth Mountains southeast of Livingston, by Berg, R.B., Lopez, D.A., and Lonn, J.D., 2000, Geologic Map of the Livingston 30’ X 60’ Quadrangle, South-Central Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Open File No. 406, scale 1:100,000; http://mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf_100k/livingston.pdf

Geologic Map of Cody Quadrangle that covers southeast edge of Beartooth Mountains by Pierce, W.G., 1997, Geologic map of the Cody 1 degree X 2 degree quadrangle, northwestern Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey, Miscellaneous Geologic Investigations Map I-2500, scale 1:250,000; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ngm-bin/pdp/zui_viewer.pl?id=1337.

Geologic Map of Deep Lake Quadrangle that covers southeast edge of Beartooth Mountains near Clarks Fork Canyon, by Pierce, W.G., 1965, Geologic Map of the Deep Lake Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey GQ-478, scale 1:62,500;https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_13113.htm

Geologic Map of the Beartooth Butte Quadrangle that covers the southern part of Beartooth Mountains, by Pierce, W.G., and Nelson, W.H., 1971, Geologic Map of Beartooth Butte Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey GQ-935, scale 1:62,500;https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_2235.htm

Geologic Map of Pilot Peak Quadrangle that covers south edge of Beartooth Mountains near Cooke City, by Pierce, W.G, Nelson, W.H. and Prostka, H.J., 1973, Geologic Map of the Pilot Peak Quadrangle, Park County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Geologic Investigations Map I-816; scale 1:62,500; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_13015.htm

Things To Do in the Beartooth Mountains

Beartooth Highway Road Opening

When the road opens for the Memorial Day weekend, it still looks and can feel like winter up in the Beartooths. Take a scenic drive to see the thick plowed snowdrifts, throw snowballs, scratch a message in the walls of snow, cross country ski and/or saucer sled on a gentle slope. If you are into extreme skiing, a couple hours of skiing at the Beartooth Basin Ski Area followed by a ski of the Gardiner Headwall and a hike out of the Gardiner Basin is something to remember and brag about. It is best to do the Beartooth Mountain Highway drive as a loop that includes the Chief Joseph Scenic Highway (WY 296) through the Clarks Fork Valley, Sunlight Basin and over Dead Indian Hill and then back to Red Lodge via Belfry.

Skiing the chutes above the Beartooth Highway switchbacks in early June

Photo by Mark Fisher

Photo by Mark Fisher

Beartooth Waterfalls

Peak runoff occurs during the beginning of June and the waterfalls are awesome and powerful. View Beartooth Falls from the highway just below Beartooth Lake, take a short walk to Lake Creek Falls at the highway bridge and a short walk to the cascades at Lake Creek Campground (Chief Joseph Highway WY 296), and the ultimate is a short walk to see Crazy Creek Falls off US 212 heading toward Cooke City across from the Crazy Creek Campground. Crazy Creek’s immense water flow, thunderous sound and cold mist is worth a trip every year.

Crazy Creek Falls in early June

Photo by Mark Fisher

Photo by Mark Fisher

Beartooth Day Hikes

Hiking from lake to lake at timber line and just above timber line is spectacular in the Beartooths. My favorite day hikes are: 1) Trail to Glacier Lake and Emerald Lake that starts at the end of the Forest Service Road 2421 up the main fork of Rock Creek, 2) Island Lake to Night Lake to Beauty Lake on top of the Beartooths accessed at Island Lake Campground, 3) Dorf Lake to Lower and Upper Sheepherder Lakes on top of the Beartooths accessed by a trail that starts at the end of a short dirt road between Long Lake and Little Bear Lake, and 4) Twin Lakes accessed by a trail that starts at a pulloff near the Montana-Wyoming state line. With all the lakes and marshy areas in the Beartooths, mosquitoes are an overwhelming force in July and August. If you hike in June or early July, not many mosquitoes but the trails are snowy and swampy. We often wait until a freeze happens in the high country during early September before hiking in the Beartooths.

Beartooth Boating

Taking your canoe, kayak, or small boat to Island Lake or Beartooth Lake for fishing or just exploring is peaceful and wonderful.

The material on this page is copyrighted