View to southwest of Bear Canyon on south flank of Big Pryor Mountain

Photo by Mark Fisher

Photo by Mark Fisher

Wow Factor (4 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (4 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Erosion has carved rugged canyons, ravines and caves in uplifted Madison carbonate rocks. Major faulting along the north and east sides of the mountain blocks results in steep flanks. Minimal faulting to the west and south results in gentle dip into the Bighorn Basin. Isolated, mostly dry mountains with wide open vistas. South half of range is National Forest/BLM with public access. North half of range is Crow Indian Reservation.

History of Pryor Mountains

July 1806, 1st Sergeant Nathaniel Hale Pryor of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery was in command of a squad herding horses bought from the Nez Perce for trade at a Mandan village. A band of Crow Indians took all 65 horses in two stealthy nighttime raids in the Yellowstone River valley. The squad unsuccessfully attempted to apprehend the Indians and recover the herd near a mountainous area just north of the Wyoming border. Today that area bears the sergeant’s name, Pryor Mountains.

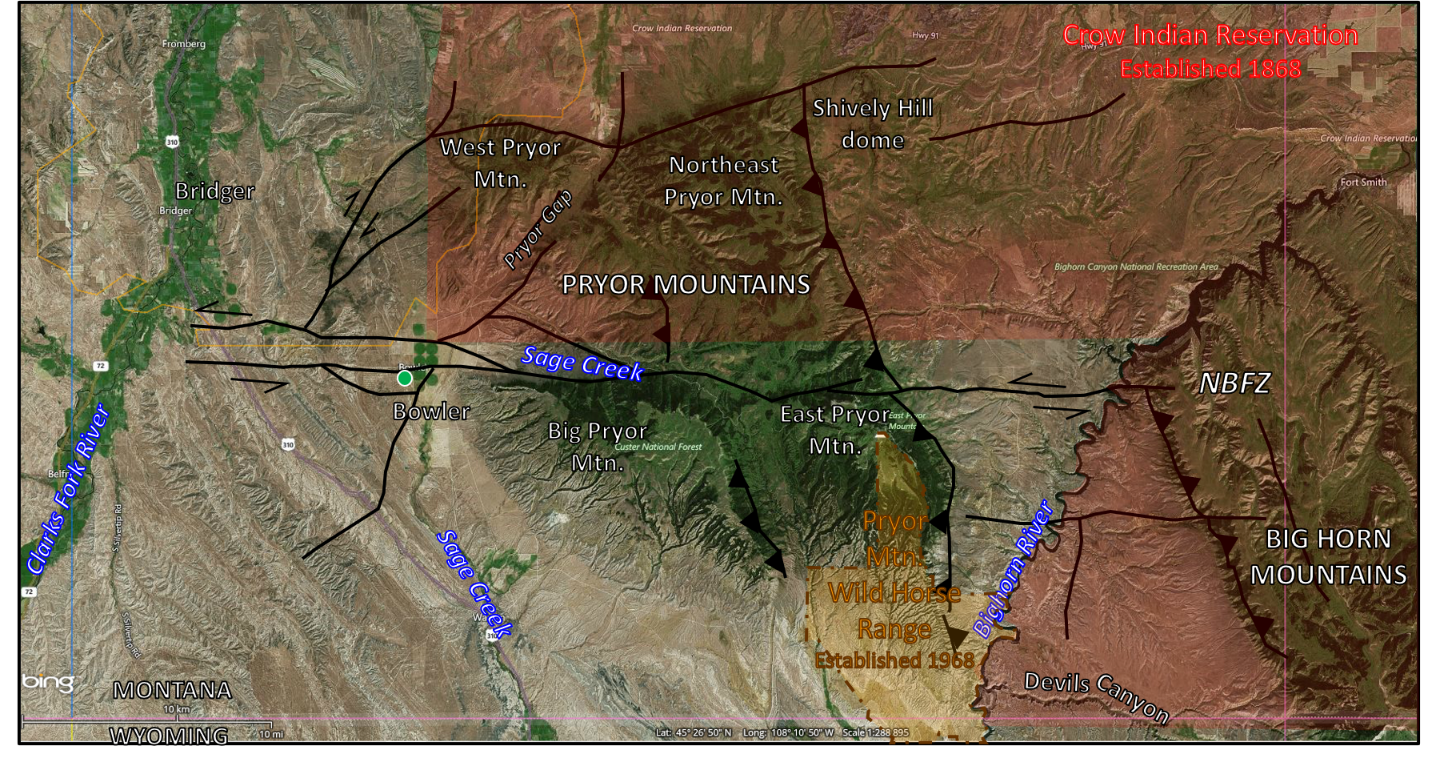

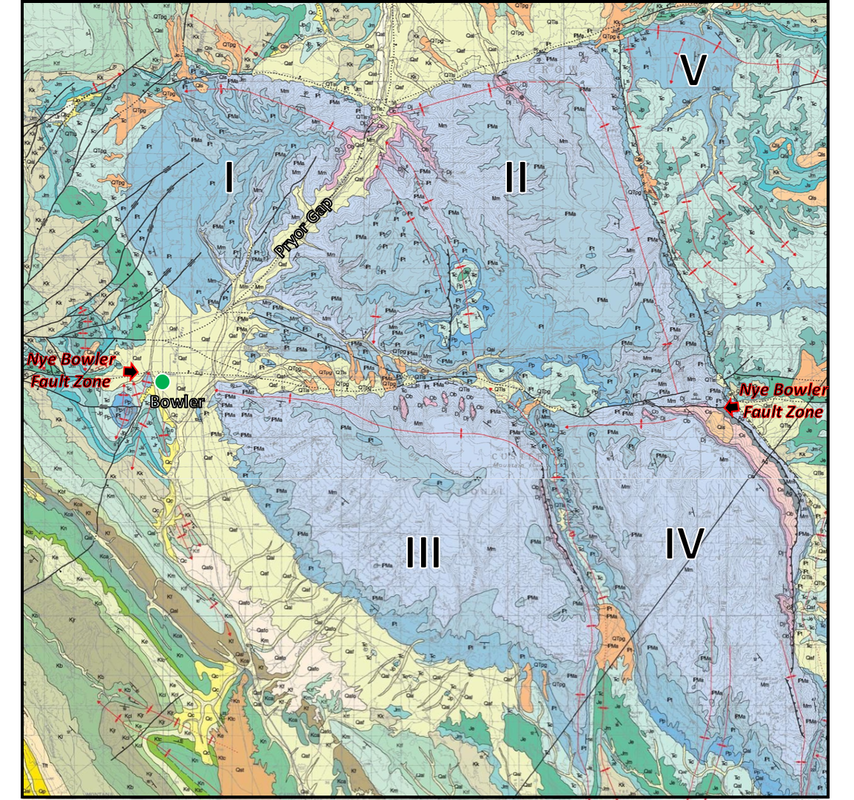

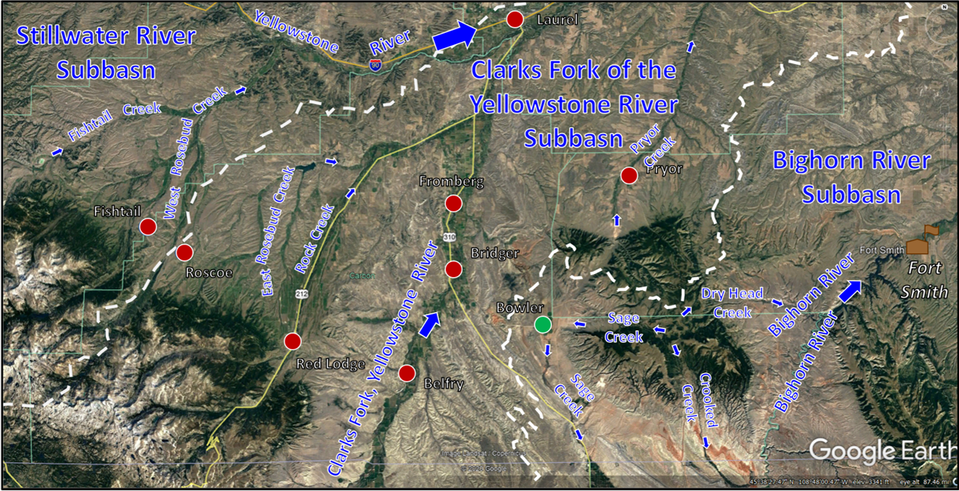

Pryor Mountains, South Central Montana. The five blocks of the range are labeled. Faults: Reverse - sawteeth on upthrown side, Lateral - main direction shown by arrows, NBFW- Nye Bowler fault zone. Towns: Active (red) & abandoned (green).

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

The Crow people are a nomadic Plains Indian tribe that migrated into the Yellowstone River valley and Pryor Mountain region by the late 17th century. They adopted the horse culture about the same time. They called the mountains “Hitting Rock Mountains” (Baahpuuo Isawaxaawu) for the abundance of chert and flint that they used for projectile points and tools. The U.S. government recognized their land in the first Laramie Treaty of 1851. The tribe’s relationship with the government was more favorable than most other tribes and many Crow braves volunteered as U.S. Army scouts during the Sioux Wars (1854-1890).

Northwest view of Pryor Mountains from Devils Canyon

Image: Walton, D., 2020, in Regale, R. & G., and Otstot, R, Jan. 23, 2020, Guest view: E-bikes threaten the fragile Pryor Mountains ecosystem: Billings Gazette; https://billingsgazette.com/opinion/columnists/guest-view-e-bikes-threaten-the-fragile-pryor-mountains-ecosystem/article_cffa5b91-773a-59fd-a0d4-267dc5ab40c8.html

Image: Walton, D., 2020, in Regale, R. & G., and Otstot, R, Jan. 23, 2020, Guest view: E-bikes threaten the fragile Pryor Mountains ecosystem: Billings Gazette; https://billingsgazette.com/opinion/columnists/guest-view-e-bikes-threaten-the-fragile-pryor-mountains-ecosystem/article_cffa5b91-773a-59fd-a0d4-267dc5ab40c8.html

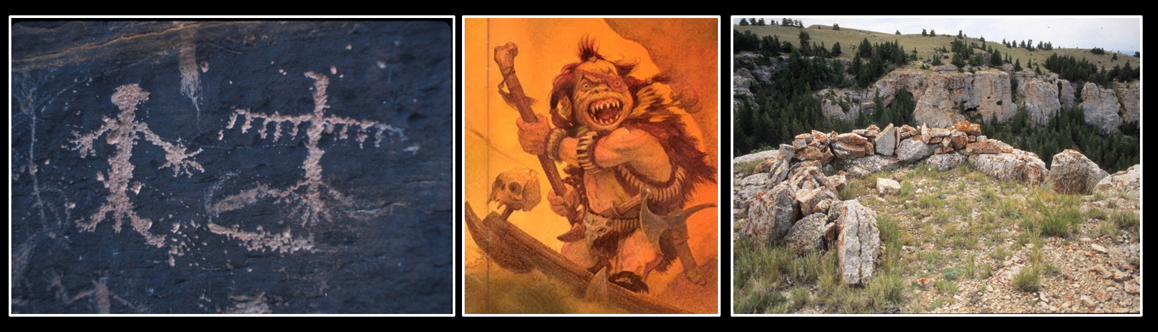

According to Crow legend, a race of aggressive “Little People,” known as Nirumbee inhabited the Pryor Mountains. These mythical beings were about eighteen inches tall, had large heads and pointed teeth. They were friendly with the Crow who respected them and left small gifts for them. Petroglyphs were thought to be evidence of their presence in the mountains long before the Crow arrived. The Pryors were considered sacred to the Crow because Little People lived there.

Left: Pictograph, Pryor Mountains; Center: Artist rendering of a Nirumbee, Pryor Mountain's little people; Right: Vision quest structure.

Images: Left: http://www.pryormountains.org/welcome-to-the-pryors/photos/; Center:https://thecuriousforteanweb.wordpress.com/2017/09/23/pryor-mountain-little-people-the-nirumbee/; Right: http://www.pryormountains.org/cultural-history/archaeology/vision-quest-structures/.

Images: Left: http://www.pryormountains.org/welcome-to-the-pryors/photos/; Center:https://thecuriousforteanweb.wordpress.com/2017/09/23/pryor-mountain-little-people-the-nirumbee/; Right: http://www.pryormountains.org/cultural-history/archaeology/vision-quest-structures/.

Archaeologists date human presence in the Pryors from about 12,000 years ago. Prehistoric hunter gathers left hundreds of sites on the mountains including tipi rings, quarries, rock cairns, wickiups and crib-log structures, vision quest locations, pictograph and petroglyph sites, and fire hearths. Chert nodules within the Madison were used by prehistoric (10,000 B.C. to A.D. 1800) hunter-gatherers for stone tools and projectile points.

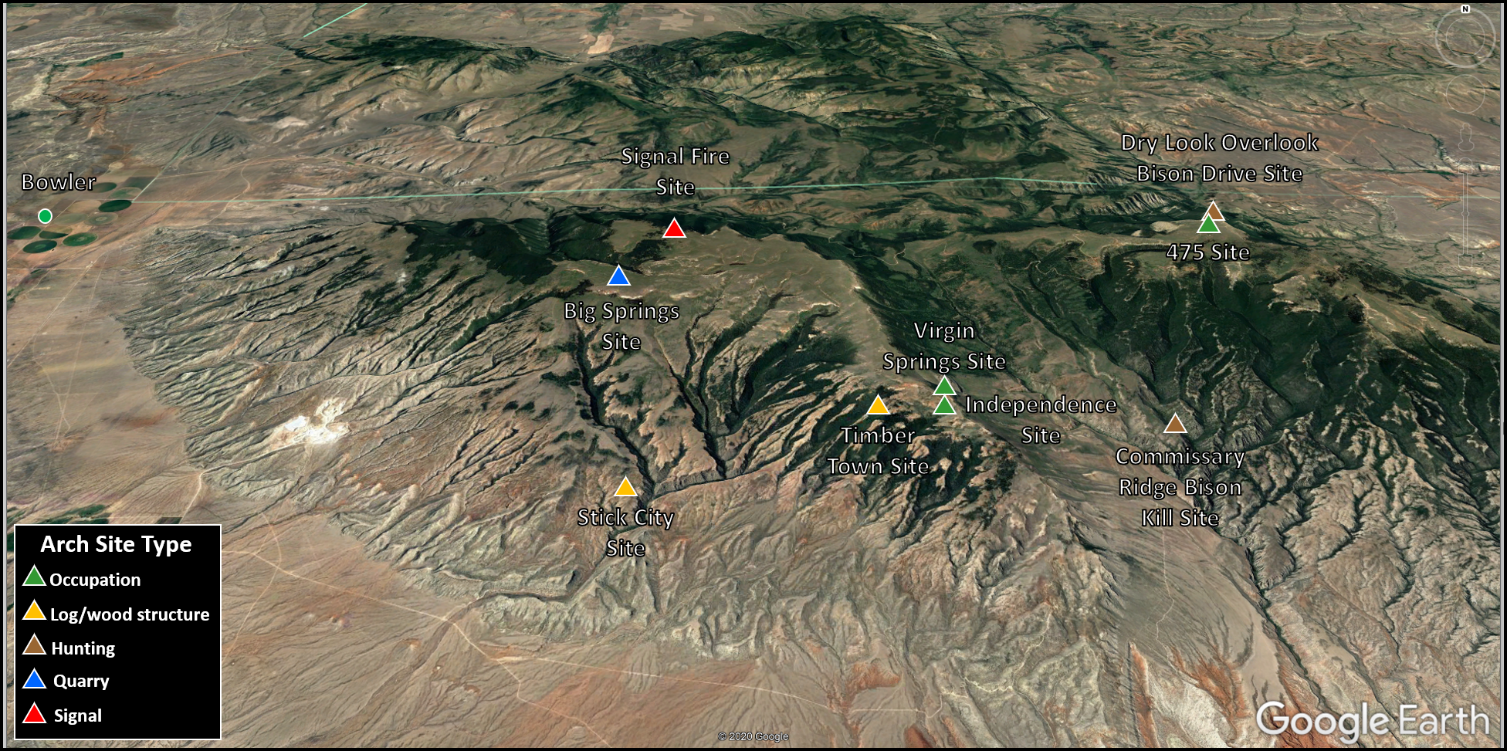

Selected Paleo-Indian sites in southern Pryor Mountains. The area also includes about 100 vision quest structures that are not shown.

Image: Google Earth; Data: After Good, Kent N., 1974, Survey and synthesis of archaeological sites within the sub-alpine ecological zone, Pryor Mountains, Montana: PhD Thesis, University of Montana University of Montana: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3790.

Image: Google Earth; Data: After Good, Kent N., 1974, Survey and synthesis of archaeological sites within the sub-alpine ecological zone, Pryor Mountains, Montana: PhD Thesis, University of Montana University of Montana: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3790.

Geology of the Pryor Mountains

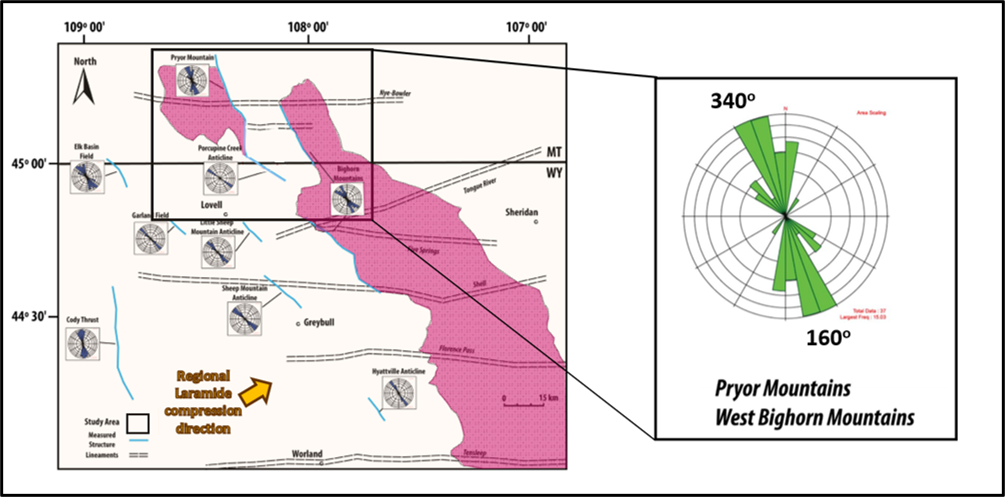

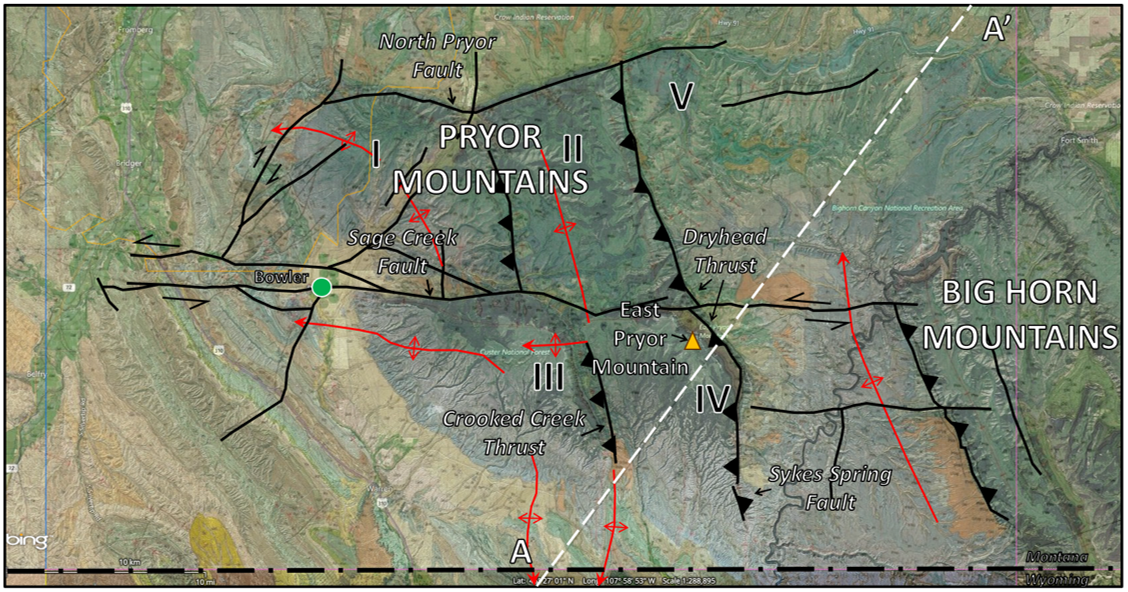

The Pryor Mountains are 30 miles south of Billings in south-central Montana. The structure is about 15 miles east-west and 25 miles north-south. The Pryors lie at the boundary intersection of major Laramide (late Cretaceous to early Eocene) tectonic structures, including Bull Mountain basin (north), Powder River basin (northeast & east), Bighorn basin (southwest, south & southeast), and the Nye Bowler fault zone cutting through the Pryors (west-east). The range consists of four major fault blocks (I: West, II: Northeast, III: East, and IV: Big Pryor mountains; and a small dome, V: Shively Hill). Regional structural orientation is north-northwest by south-southeast, consistent with Laramide northeast directed compression. Tectonism that reactivated Precambrian basement zones of weakness reached the Pryor Mountain area about 70 million years ago and lasted 15 to 20 million years.

Regional structural trend analysis of northeast Bighorn Basin (left) and Pryor and Bighorn Mountain areas (right).

Image: After Eldam, N.S., 2012, Structural Controls on Evaporite Paleokarst Development: Mississippian Madison Formation, Bighorn Canyon Recreation Area, Wyoming and Montana: M.S. Thesis University of Texas, Austin, Figs 2.3 & 2.14, p. 34 & 52; https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2012-05-5134.

Image: After Eldam, N.S., 2012, Structural Controls on Evaporite Paleokarst Development: Mississippian Madison Formation, Bighorn Canyon Recreation Area, Wyoming and Montana: M.S. Thesis University of Texas, Austin, Figs 2.3 & 2.14, p. 34 & 52; https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2012-05-5134.

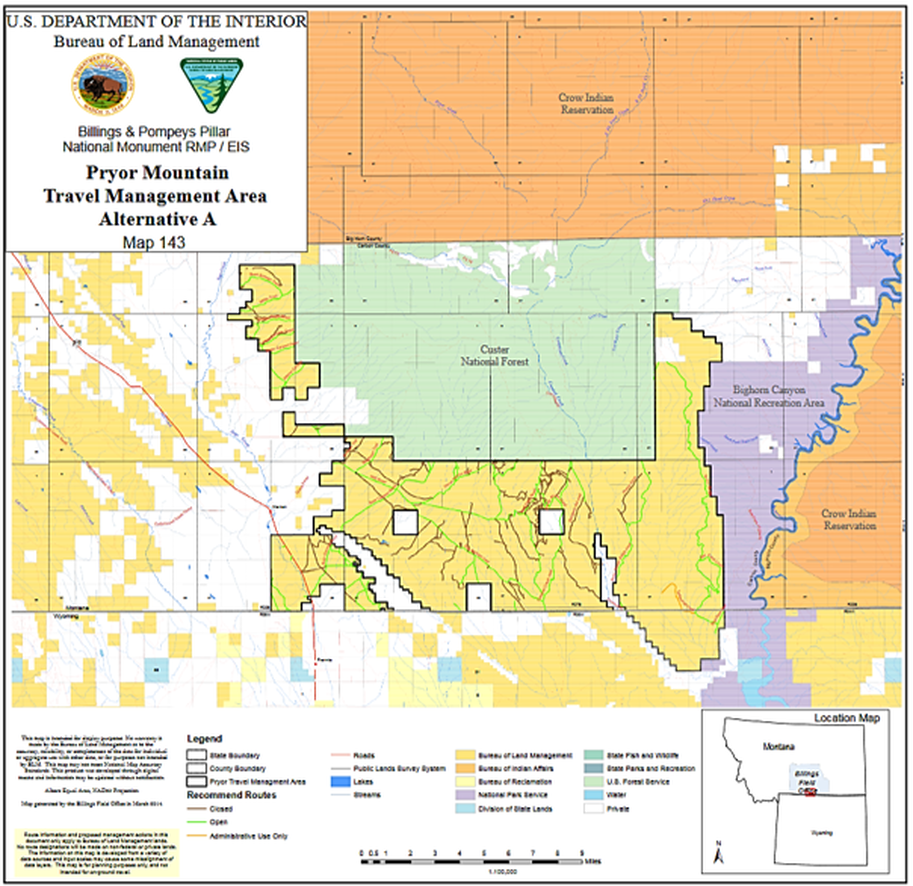

The tilted blocks are bound by left-lateral vertical faults to the north, and by northeast moving thrusts on the east flank. Highest elevations are at the northeastern block margins. The Nye Bowler fault zone separates the northern blocks (I, II, & V) on the Crow Reservation from the southern blocks (III & IV) managed by the U.S. Forest Service (Custer National Forest) and the Bureau of Land Management.

The sedimentary rocks exposed in the Pryor Mountains span about 400 million years of geologic time. The strata overlie 3 to 4 billion-year-old igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks of the Wyoming Craton. The mountains expose Mississippian Madison Limestone (mainly blocks II, III, & IV) over a large area. The carbonate landscape developed a highly dissected karst topography. The Pryor’s are noted for numerous canyons, caves, and rock shelters. The Madison Limestone provided prehistoric people shelter, rock art “canvas,” chert for knapping tools, and bison. Perennial streams are limited in the Pryor Mountains because the surface water seeps into the highly fractured Madison carbonates.

The sedimentary rocks exposed in the Pryor Mountains span about 400 million years of geologic time. The strata overlie 3 to 4 billion-year-old igneous and metamorphic crystalline basement rocks of the Wyoming Craton. The mountains expose Mississippian Madison Limestone (mainly blocks II, III, & IV) over a large area. The carbonate landscape developed a highly dissected karst topography. The Pryor’s are noted for numerous canyons, caves, and rock shelters. The Madison Limestone provided prehistoric people shelter, rock art “canvas,” chert for knapping tools, and bison. Perennial streams are limited in the Pryor Mountains because the surface water seeps into the highly fractured Madison carbonates.

Uplifted structural blocks, Pryor Mountains. Roman numerals: I – West Pryor, II – Northeast Pryor, III – Big Pryor, IV – Southeast Pryor, & V – Shively Hill dome. Anticlines (folds) are shown in red lines with arrows indicating direction of plunge, faults in black lines with sawtooth symbol on upthrown side of reverse faults.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Map of land management areas, Pryor Mountains. Green is Forest Service, dark yellow is BLM, light yellow is Bureau of Reclamation, orange is Crow Indian Reservation, purple is National Parks Service, blue is Wyoming State Lands and white is private.

Image: https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front-office/projects/lup/72501/120494/147144/Map143PryorsAltA24x24.pdf

Image: https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front-office/projects/lup/72501/120494/147144/Map143PryorsAltA24x24.pdf

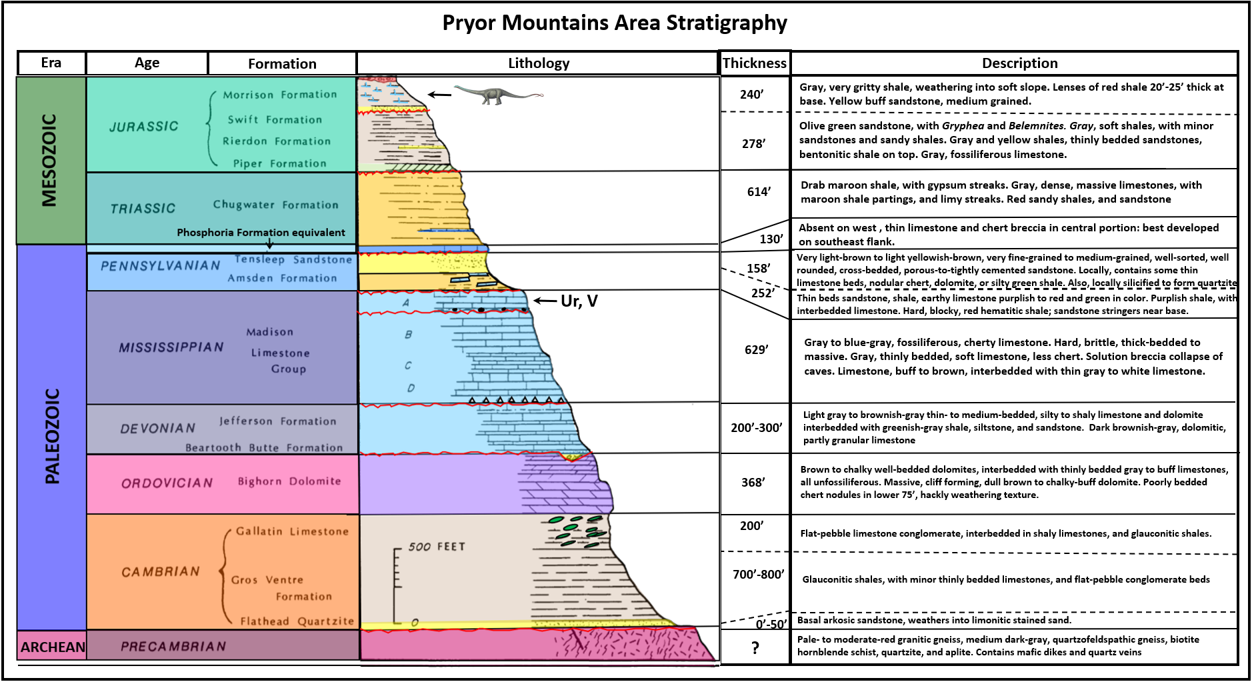

Stratigraphic column of rocks exposed in Pryor Mountains area.

Image: After Van Gosen, B.S., Wilson, A.B., and Hammarstrom, J.M. with a section on Geophysics by Dolores M. Kulik, D.M., 1996, Mineral Resource Assessment of the Custer National Forest in the Pryor Mountains, Carbon County, South-Central Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 96-256, Fig. 3, p. 6; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1996/0256/report.pdf; and Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1940, Structure of the Pryor Mountains Montana: The Journal of Geology, Volume 48, Number 6, Table 1, p. 593-595; https://www.jstor.org/stable/30058701?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_content.

Image: After Van Gosen, B.S., Wilson, A.B., and Hammarstrom, J.M. with a section on Geophysics by Dolores M. Kulik, D.M., 1996, Mineral Resource Assessment of the Custer National Forest in the Pryor Mountains, Carbon County, South-Central Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 96-256, Fig. 3, p. 6; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1996/0256/report.pdf; and Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1940, Structure of the Pryor Mountains Montana: The Journal of Geology, Volume 48, Number 6, Table 1, p. 593-595; https://www.jstor.org/stable/30058701?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_content.

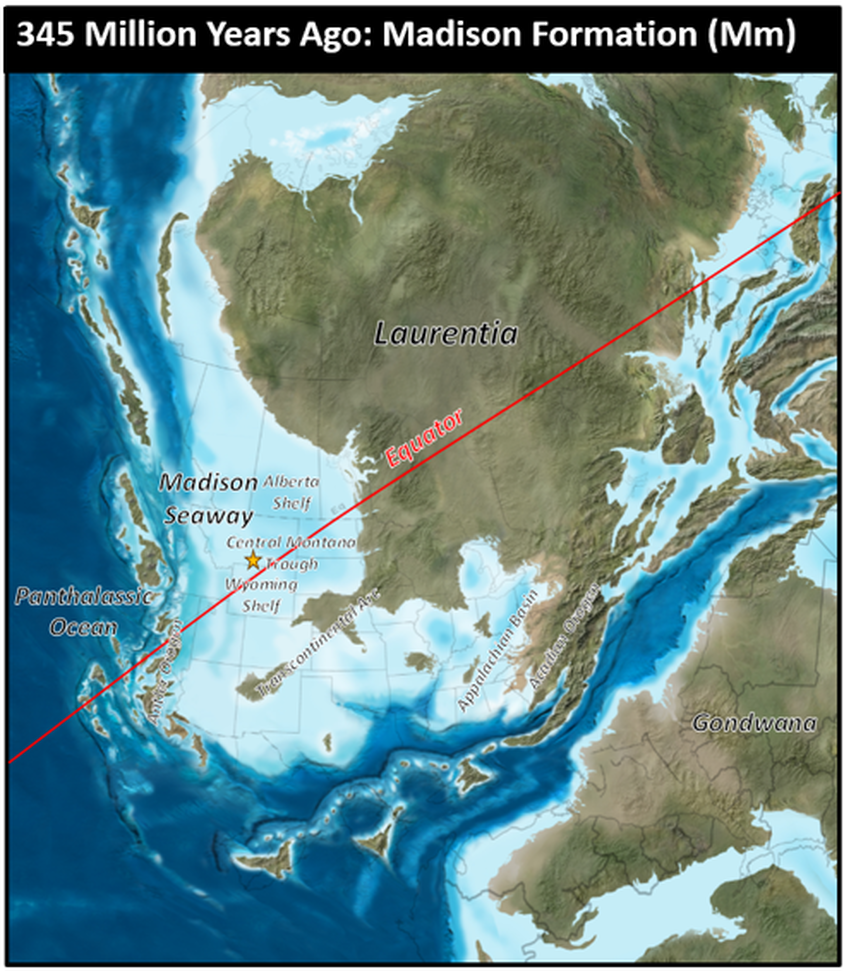

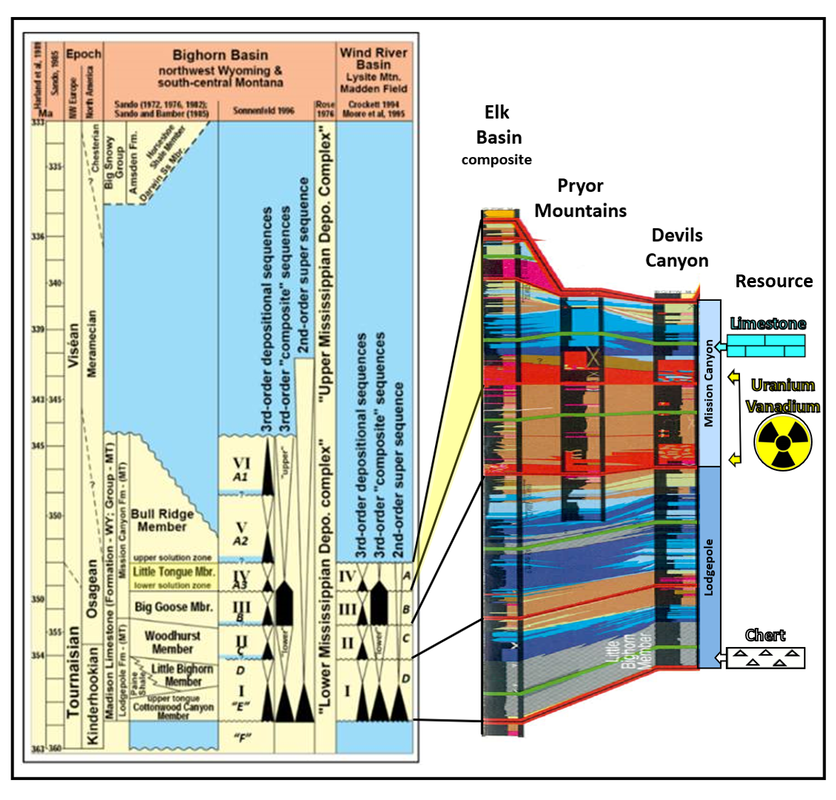

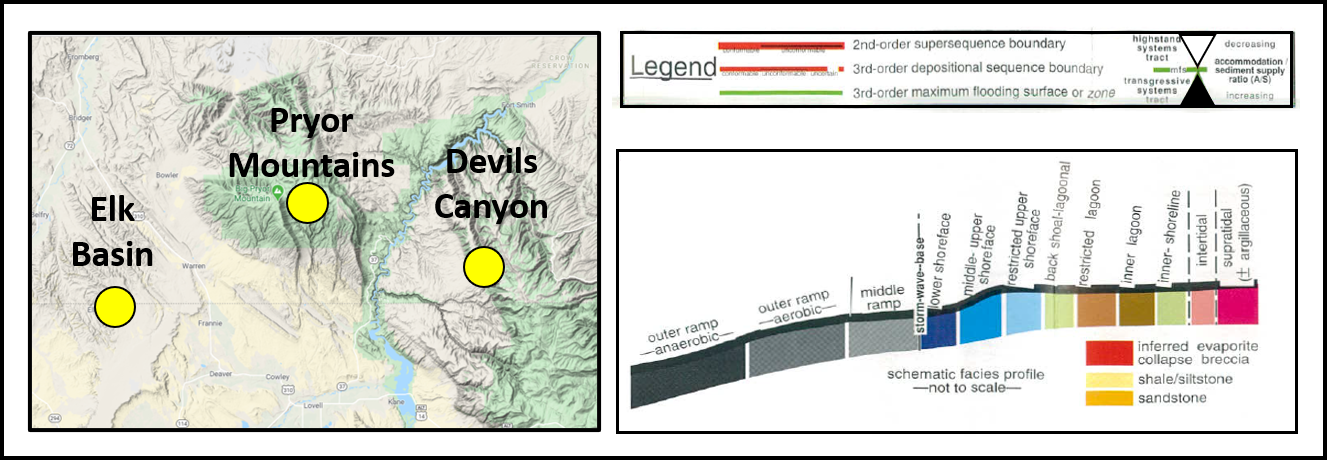

The Pryor Mountain area was a gently warped surface covered by a warm shallow ocean 345 million years ago. Over 600 feet of cherty fossiliferous carbonate rocks of the Madison accumulated on this northern portion of the Wyoming shelf. After the seaway withdrew and before the Amsden transgression, the region was exposed to subaerial erosion for 34 million years. Karst topography and solution collapse developed in the carbonate and evaporite beds. The upper Madison “A” zone (Little Tongue Member) is bounded by regional solution collapse zones and breccia deposits. Today, a series of steep walled canyons are cut in the Madison surface by streams flowing off the blocks. The Madison outcrops are a recharge area for the groundwater aquifer. The Pryors form the drainage divide between the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone and the Bighorn rivers. Both streams are tributaries of the Yellowstone river. The water and carried sediment eventually reach the Gulf of Mexico via the Missouri and Mississippi drainage complex.

Mississippian Madison Formation paleogeography, 345 million years ago. The future Pryor Mountains are shown by the gold star.

Image: After Blakey, R., Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Arizona USA.

Image: After Blakey, R., Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Arizona USA.

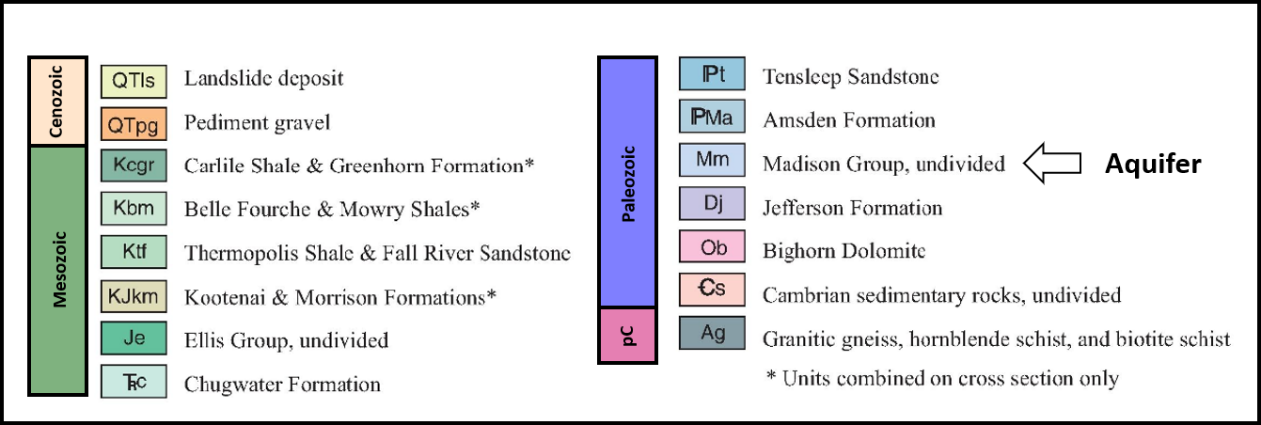

Geologic map of the Pryor Mountains, with blocks numbered. Note large exposure of the Madison (Mm) aquifer in light blue and only a tiny exposure of Precambrian on the northeast corner of Block IV in gray.

Image: After Lopez, D.A., 2000, Geologic map of the Bridger 30'x60' quadrangle, Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Geologic Map GM-58, scale 1:100,000; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_32560.htm.

Image: After Lopez, D.A., 2000, Geologic map of the Bridger 30'x60' quadrangle, Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Geologic Map GM-58, scale 1:100,000; https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_32560.htm.

Subbasins of the Yellowstone Basin drainage system in the Pryor Mountain region. Arrows show water flow directions. Dots show towns: red – active; green – abandoned. Dashed white lines are boundaries of drainage subbasins.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

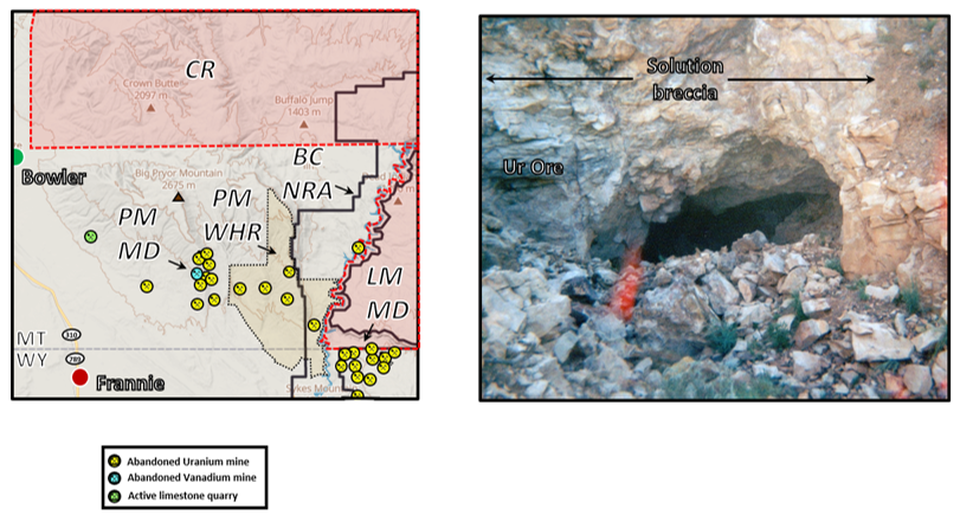

Radioactive uranium and vanadium ore were mined from 1956 to 1970 at several sites in the southern Pryor Mountain and Little Mountain districts (southeast of Pryors). Solution breccias developed from water moving through fractures, joints, and faults, dissolving evaporite beds (“A” zone). Ore concentrated in sediment filled collapse breccia in a 10 to 60-foot zone in the upper 100 to 200 feet of Madison carbonate. The mines are abandoned today, but exposure remains a concern for groundwater and cavers. The BLM reclaimed ten of these sites in 2006.

Left: Abandoned Uranium and Vanadium mine in Pryor Mountains region. Abbreviations: CR – Crow Reservation, BCNRA – Bighorn Canyon National Recreation area, LMMD – Little Mountain Mining District, PMMD – Pryor Mountain Mining District, PMWHR – Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range. Right: Abandoned Uranium mine.

Image: Left: Base Google Map; Data: Eggers, M.J., Anita L. Moore-Nall, A.L., Doyle, J.T., Lefthand, M.J, Young, S.L., Bends, A.L., Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee, and Camper, A.K., 2015, Potential Health Risks from Uranium in Home Well Water: An Investigation by the Apsaalooke (Crow) Tribal Research Group: Geosciences, 5, Fig. 1, p. 70; https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/5/1/67; Right: https://www.campingbastards.com/2018/12/places-to-see-while-camping-in-or-near.html.

Image: Left: Base Google Map; Data: Eggers, M.J., Anita L. Moore-Nall, A.L., Doyle, J.T., Lefthand, M.J, Young, S.L., Bends, A.L., Crow Environmental Health Steering Committee, and Camper, A.K., 2015, Potential Health Risks from Uranium in Home Well Water: An Investigation by the Apsaalooke (Crow) Tribal Research Group: Geosciences, 5, Fig. 1, p. 70; https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/5/1/67; Right: https://www.campingbastards.com/2018/12/places-to-see-while-camping-in-or-near.html.

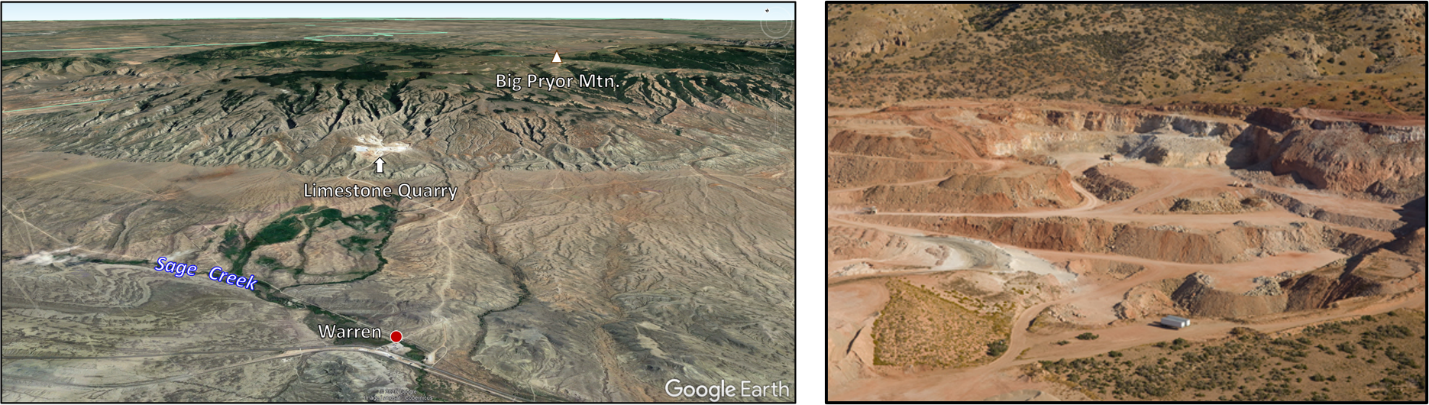

Limestone has been quarried from the Upper Madison Mission Canyon beds five miles northeast of Warren, Montana since the 1950s. The stone has purity averages of 80 to 85 percent calcium, with some zones over 95 percent level. It is used by agriculture (sugar beets), decorative stone and construction industries.

Limestone quarry near Warren, Montana

Image: Left: Google Earth; Right: https://basinelectric.wordpress.com/2009/04/16/two-millionth-ton-of-lime-in-the-books/.

Image: Left: Google Earth; Right: https://basinelectric.wordpress.com/2009/04/16/two-millionth-ton-of-lime-in-the-books/.

Madison Limestone lithostratigraphic chronology and sequence stratigraphic cross-section of Pryor Mountains area. Uranium and vanadium ore generally occur in solution breccia zones within the Little Tongue member of the Madison Formation (“A” unit). Limestone is quarried from the upper Madison Mission Canyon Beds.

Image: After Eldam, N.S., 2012, Structural Controls on Evaporite Paleokarst Development: Mississippian Madison Formation, Bighorn Canyon Recreation Area, Wyoming and Montana: M.S. Thesis University of Texas, Austin, Figs 1.9-1.10, p. 18-19; https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2012-05-5134.

Image: After Eldam, N.S., 2012, Structural Controls on Evaporite Paleokarst Development: Mississippian Madison Formation, Bighorn Canyon Recreation Area, Wyoming and Montana: M.S. Thesis University of Texas, Austin, Figs 1.9-1.10, p. 18-19; https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2012-05-5134.

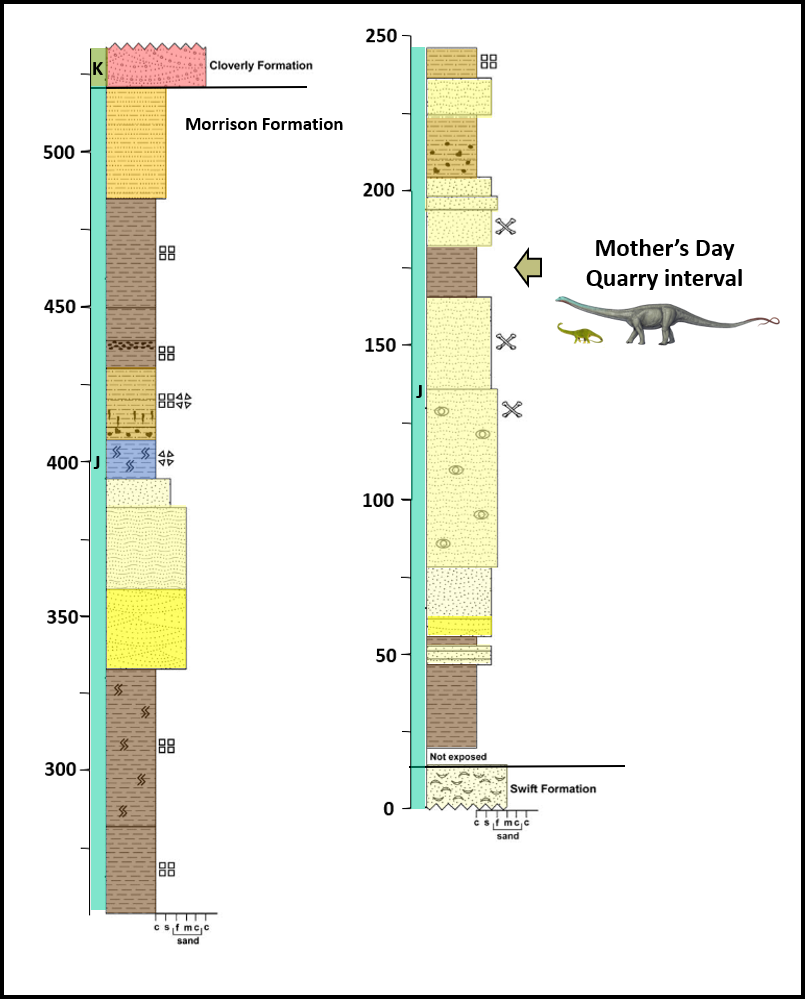

The Jurassic Morrison Formation (155-148 million years ago) and equivalent units were deposited in a vast basin by streams eroding the western mountains. They signal the start of the Sevier Orogeny of the Cordilleran Thrust Belt. In 1995, dinosaur remains were discovered and named the Mother’s Day site. The quarry has produced numerous bones and some skin from juvenile diplodocus sauropods. The site is about five miles west of Bowler on the west flank of a small subsidiary anticline west of the Pryors. The area lies between Bridger Creek (east and north) and South Fork Creek (west).

Jurassic Morrison Formation paleogeography, 150 million years ago. The future Pryor Mountains are shown by the gold star.

Image; After Blakey, R., Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Arizona USA.

Image; After Blakey, R., Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Arizona USA.

Mother’s Day dinosaur quarry site location map (green star) and Pryor Mountains (yellow star) Montana.

Image: After Myers, T.S., 2004, Taphonomy of the Mother’s Day Quarry: Implications for Gregarious Behavior in Sauropod Dinosaurs: M.S. Thesis University of Cincinnati, Fig. 1, p. 8; https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/TAPHONOMY-OF-THE-MOTHER'S-DAY-QUARRY%3A-IMPLICATIONS-Myers/58f0182120beda0330a52f23a05926a6e2572701#paper-header

Image: After Myers, T.S., 2004, Taphonomy of the Mother’s Day Quarry: Implications for Gregarious Behavior in Sauropod Dinosaurs: M.S. Thesis University of Cincinnati, Fig. 1, p. 8; https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/TAPHONOMY-OF-THE-MOTHER'S-DAY-QUARRY%3A-IMPLICATIONS-Myers/58f0182120beda0330a52f23a05926a6e2572701#paper-header

The Morrison formation is a clastic sequence of sandstone, siltstone, mudstone and conglomerate rocks that are variously colored red, purple, brown and gray. They are deposits of rivers and lakes (fluvial-lacustrine) that flowed into the northward retreating Sundance sea. The dinosaur beds contain rip up clasts that suggest a high energy environment. A flood stage event accounts for the assemblage and rapid burial of fossils.

Life reconstruction of juvenile Mother's day Quarry skull (CMC VP14128). Note the cranial morphologies interpreted to denote differing feeding strategies: in immature Diplodocus the narrow snout with posteriorly elongated and morphologically varied tooth row for bulk feeding vs. the widened snout with anteriorly restricted peg-shaped teeth for ground-level browsing in adults. Also note the camouflaged color change suggesting young diplodocids may have sought forested refuge.

Image: Atuchin, A., 2018, in D. Cary Woodruff, D.C. Thomas D. Carr, T.D., Storrs, G.W., Waskow, K., John B. Scannella, J.B., Nordén, K.K., and Wilson, J.P., The Smallest Diplodicod Skull Reveals Cranial Ontogeny and Growth-Related Dietary Changes in the Largest Dinosaurs: Scientific Reports, 2018; 8; 14341; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6181913/

Image: Atuchin, A., 2018, in D. Cary Woodruff, D.C. Thomas D. Carr, T.D., Storrs, G.W., Waskow, K., John B. Scannella, J.B., Nordén, K.K., and Wilson, J.P., The Smallest Diplodicod Skull Reveals Cranial Ontogeny and Growth-Related Dietary Changes in the Largest Dinosaurs: Scientific Reports, 2018; 8; 14341; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6181913/

Morrison Formation lithologic column of Mother’s Day Quarry, Pryor Mountains area.

Image: After Myers, T.S. and Storrs, G.W., 2007,Taphonomy of the Mother’s Day Quarry, Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, South-Central Montana, USA: PALAIOS, v. 22, Fig. 2, P.652; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Glenn_Storrs/publication/40663004_Taphonomy_of_the_Mother%27s_Day_Quarry_Upper_Jurassic_Morrison_Formation_south-central_Montana_USA/links/0912f50feb85e8c6c2000000/Taphonomy-of-the-Mothers-Day-Quarry-Upper-Jurassic-Morrison-Formation-south-central-Montana-USA.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

Image: After Myers, T.S. and Storrs, G.W., 2007,Taphonomy of the Mother’s Day Quarry, Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, South-Central Montana, USA: PALAIOS, v. 22, Fig. 2, P.652; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Glenn_Storrs/publication/40663004_Taphonomy_of_the_Mother%27s_Day_Quarry_Upper_Jurassic_Morrison_Formation_south-central_Montana_USA/links/0912f50feb85e8c6c2000000/Taphonomy-of-the-Mothers-Day-Quarry-Upper-Jurassic-Morrison-Formation-south-central-Montana-USA.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

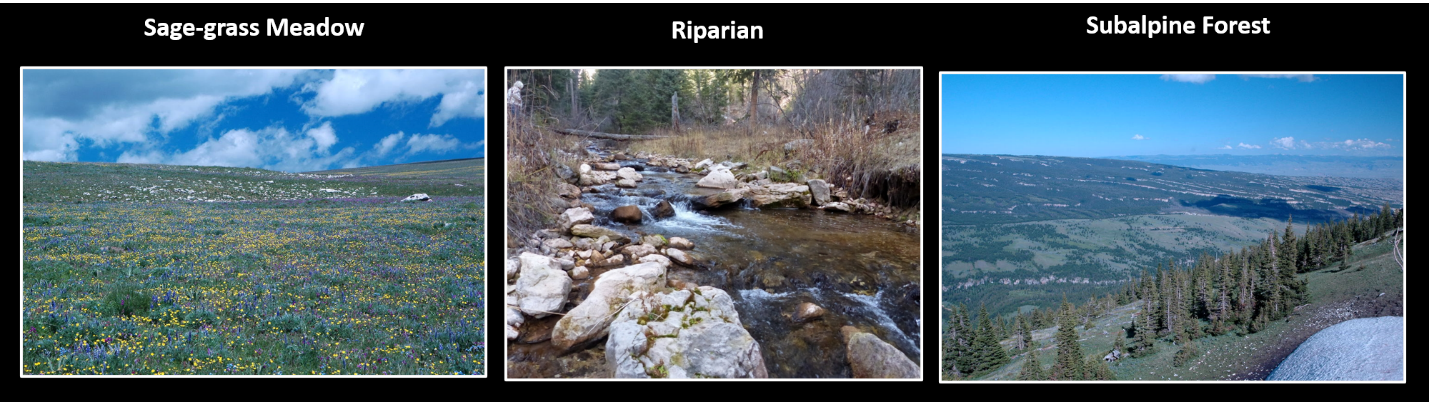

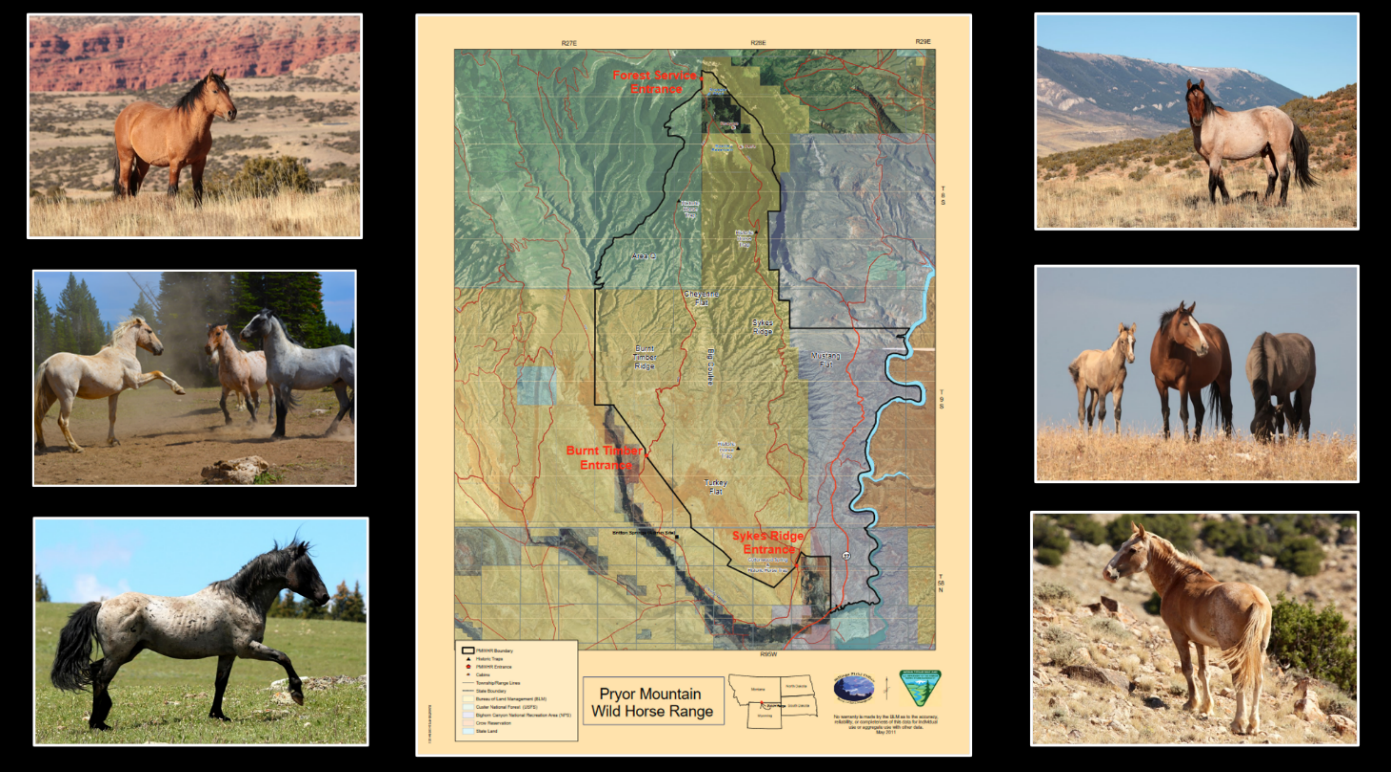

The Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range, the nation’s first wild horse management area, was created in 1968. Habitat there varies by elevation, water, and season. Vegetation ranges from shrub-grassland, river margin (riparian), to subalpine forest and meadows. Elevations vary from 3,700 to over 8,700 feet above sea level.

Pryor Mountains habitats.

Image: http://www.pryormountains.org/pryors-coalition/

Image: http://www.pryormountains.org/pryors-coalition/

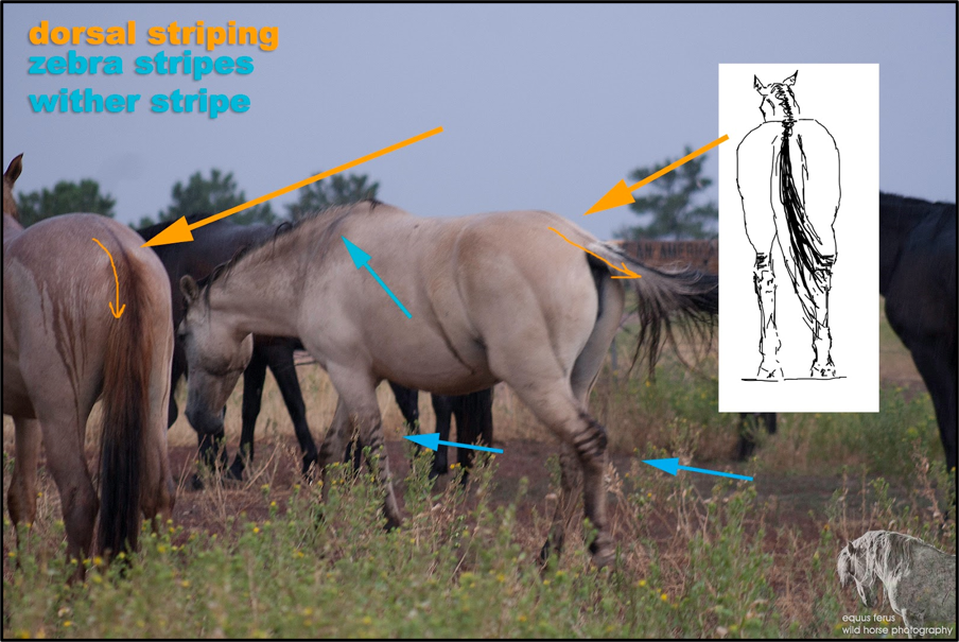

Horses had been extinct in North America for about 10,000 years until the Conquistadors reintroduced them. In 1680, during the Pueblo Uprising, many horses escaped or were captured from the Spanish. Genetic studies of the Pryor Mountain wild horses showed they have traits consistent with Spanish horses. The Pryor herds may also include bloodlines from the horses that Sergeant Pryor lost over 200 years ago in the Yellowstone Valley. Many of the Pryor horses have distinctive dorsal stripes on their backs and “zebra” stripes on their legs.

Pryor Mountains Wild Horse Range.

Image: BLM and http://www.pryormustangs.org/photo-gallery/.

Image: BLM and http://www.pryormustangs.org/photo-gallery/.

Primitive markings on Dun colored horses.

Image: Equus ferus-Wild Horse Photography & Karen McLain Studio, 2015; http://equusferuswildhorsephotography.blogspot.com/2015/12/primitive-markings-in-dun-horses.html.

Image: Equus ferus-Wild Horse Photography & Karen McLain Studio, 2015; http://equusferuswildhorsephotography.blogspot.com/2015/12/primitive-markings-in-dun-horses.html.

Things To Do

Big Pryor Mountain and East Pryor Mountain located in the southern half of the Pryor Mountains has public access on the Custer National Forest, BLM and the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. The northern half of the Pryor Mountains is located on the Crow Indian Reservation and is not open to the public.

On Big Pryor Mountain and East Pryor Mountain there are numerous places to hike. These mountains also have endless miles of dirt roads making it OHV heaven. The Pryor Mountains website has detailed descriptions and maps of how to get there, hikes, roads, camping, natural history, and cultural history.

On Big Pryor Mountain and East Pryor Mountain there are numerous places to hike. These mountains also have endless miles of dirt roads making it OHV heaven. The Pryor Mountains website has detailed descriptions and maps of how to get there, hikes, roads, camping, natural history, and cultural history.

The material on this page is copyrighted