Vertical Madison beds at Five Springs Structure on US 14 Alt

Picture by Mark Fisher

Picture by Mark Fisher

Wow Factor (5 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (4 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Goosebumps on your arms views! A steep curving road trip from the Bighorn Basin to the top of the Bighorn Mountains and back to the basin with faults, canyons, dikes, cliffs, creeks, waterfalls, meadows, hikes, rock collecting and the sacred Native American Medicine Wheel.

Geology of Bighorn Mountain Byways Part I

A road trip on the Bighorn Byways is a journey across one of the oldest pieces of North America. These 2.8 to 3.0 billion year old basement rocks of the Wyoming Craton were covered by sediments from ancient oceans for hundreds of millions of years. Tectonic forces about 70 million years ago uplifted the area into a great northwest trending arch that extended for 200 miles. Continental erosion, and accompanying sediment deposition, nearly buried the range over the next 30 million years. Regional uplift of the middle Rocky Mountains began about 5 million years ago, about the same time the Yellowstone hot spot was approaching Wyoming. Since then the area has been carved by water, wind and ice to what it is today.

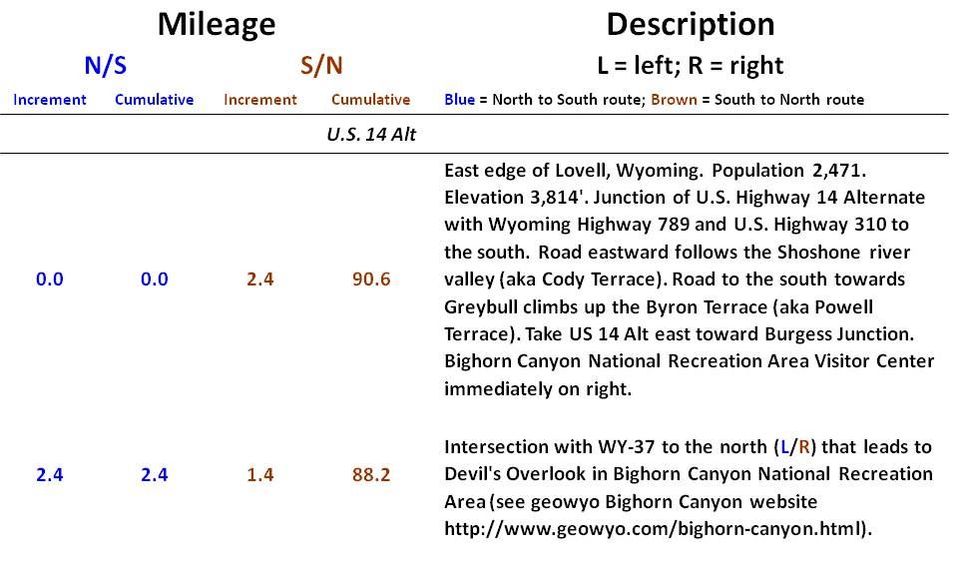

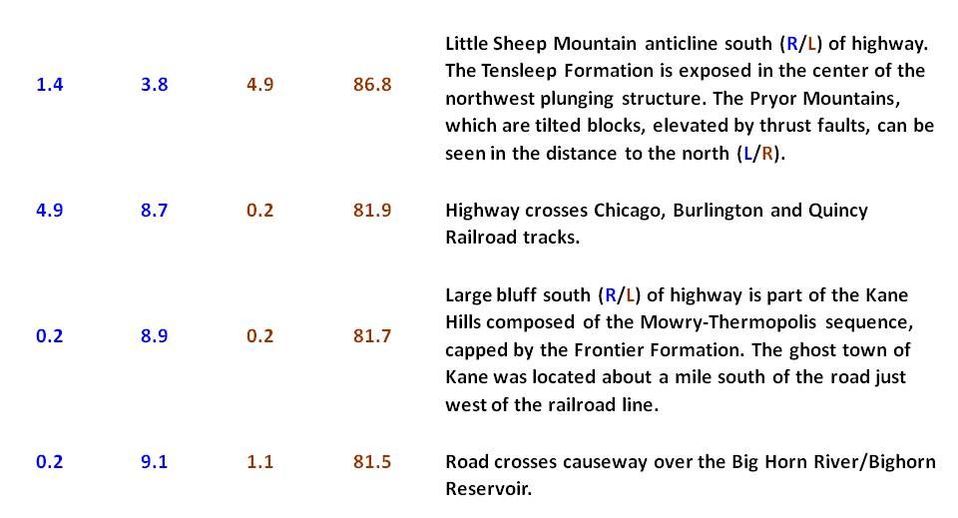

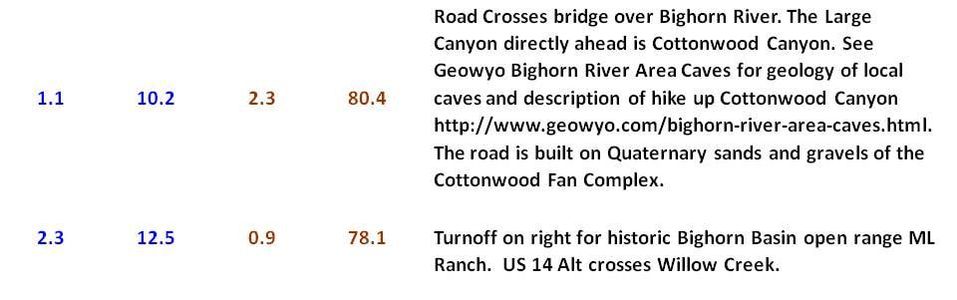

This road log is edited and compiled based on the Wyoming Geological Association Guidebooks of 1964 and 1983. Interval and cumulative mileages are reported north to south (blue) and south to north (brown) to allow travel in either direction. The north to south route is probably best choice for those not familiar with driving in the mountains. Road label and black lines are drawn between sections when the highway designation changes.

This road log is edited and compiled based on the Wyoming Geological Association Guidebooks of 1964 and 1983. Interval and cumulative mileages are reported north to south (blue) and south to north (brown) to allow travel in either direction. The north to south route is probably best choice for those not familiar with driving in the mountains. Road label and black lines are drawn between sections when the highway designation changes.

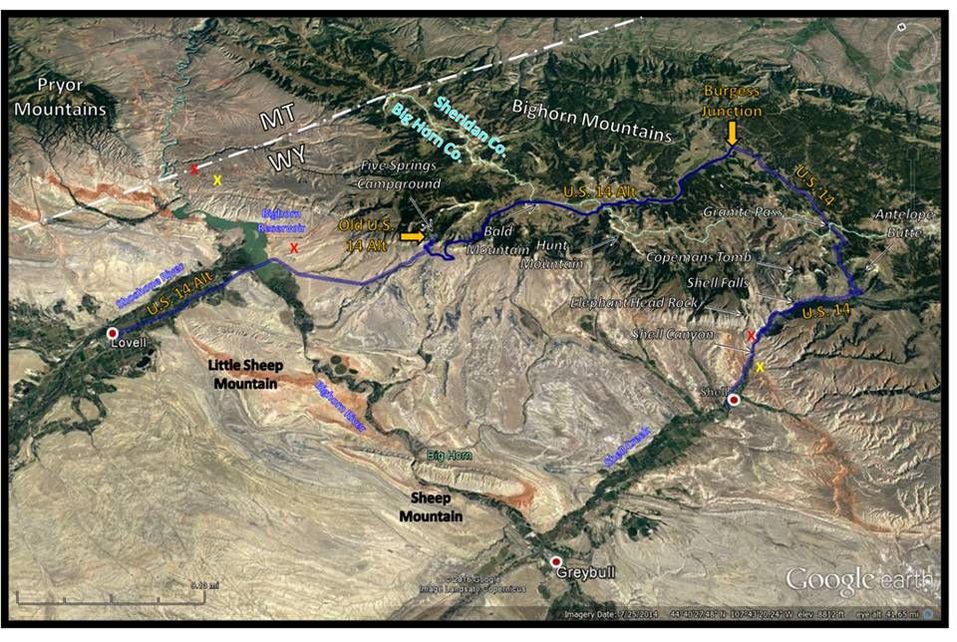

Aerial view of the Bighorn Byways loop. Route between Lovell and Shell, via Burgess Junction, is shown by the blue line. Location of ash deposits from the Yellowstone volcanic field indicated by “X”: Red: 600,000 year old Lava Creek ash; Yellow: 100,000 year old West Yellowstone ash.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Bighorn Mountain Byways Part I Geology Road Log

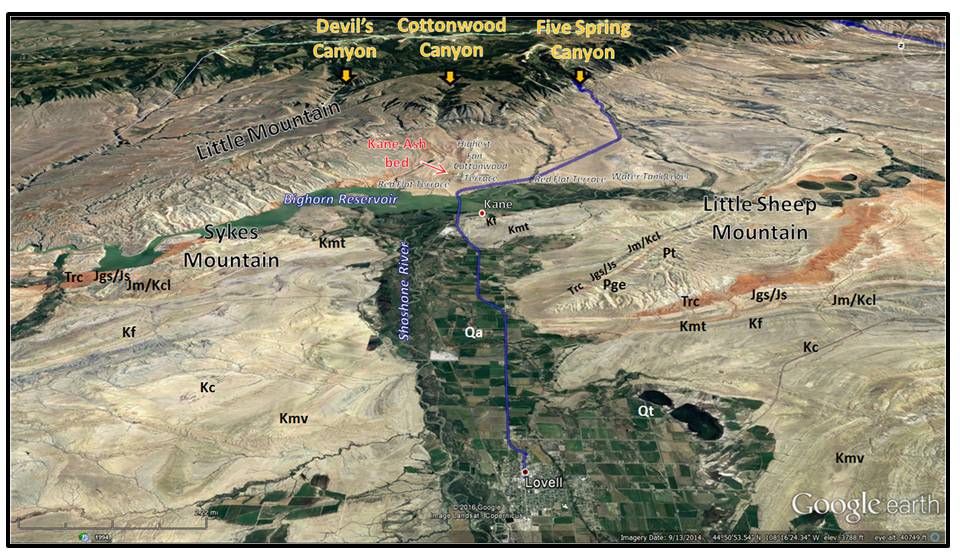

Eastward aerial view of Roadlog route from Lovell, Wyoming. Geologic notation: Qa: Quaternary alluvial deposits; Qt: Quaternary terrace deposits; Kmv: Cretaceous Mesaverde Formation; Kc: Cretaceous Cody Formation; Kf: Cretaceous Frontier Formation; Kmt: Cretaceous Mowry and Thermopolis Formations; Jm/Kcl: Jurassic Morrison and Cretaceous Cloverly Formations; Jgs/Js: Jurassic Gypsum Spring and Sundance Formations; Trc: Triassic Chugwater Formation; Pge: Permian Goose Egg Formation; Pt: Pennsylvanian Tensleep Formation The Kane Ash is an air fall deposit from the Lava Creek caldera eruption in Yellowstone Park about 600,000 years ago. The landscape in front of the Bighorn Mountains and adjacent to the river is composed of river and alluvial fan deposits.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

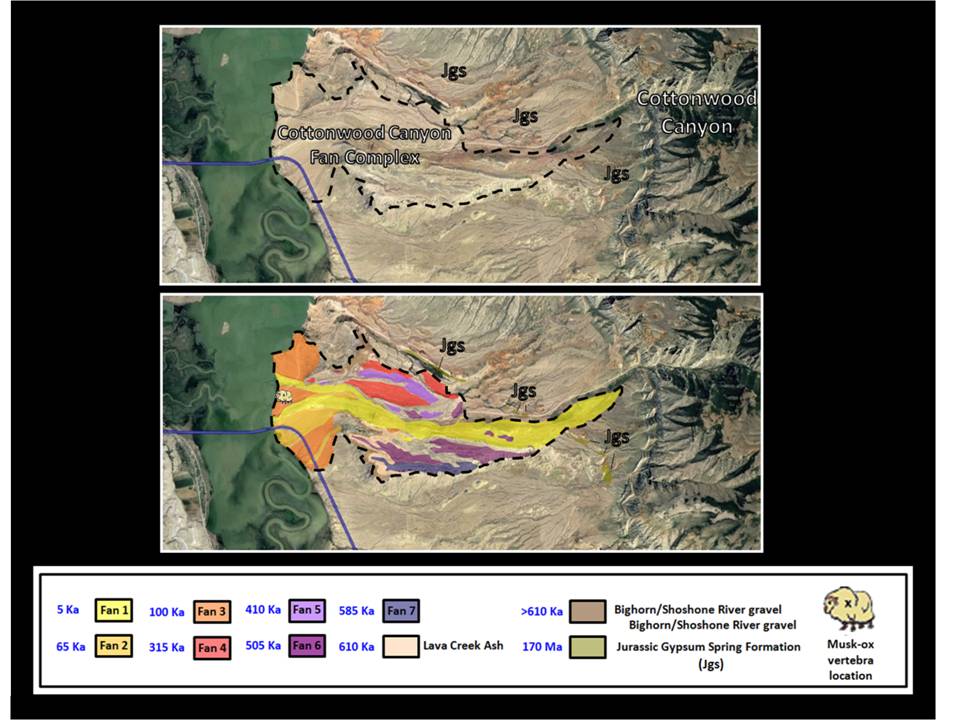

Aerial view of the Cottonwood Creek Alluvial Fan complex. Fans are colored and labeled 1 to 7, youngest to oldest. Their relative ages are shown in blue text in thousands of years (Ka) or millions of years (Ma). The lower age of Fan 3 is determined by a fossil musk ox vertebra discovered about a half-mile north of the road.

Image: Google Earth; Cottonwood Creek Fan Data: Reheis, M.C., 1987, Gypsic Soils on the Kane Alluvial Fans, Big Horn County, Wyoming: USGS Bulletin 1590-C, Fig. 2, p. C3. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1590c/report.pdf

Image: Google Earth; Cottonwood Creek Fan Data: Reheis, M.C., 1987, Gypsic Soils on the Kane Alluvial Fans, Big Horn County, Wyoming: USGS Bulletin 1590-C, Fig. 2, p. C3. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1590c/report.pdf

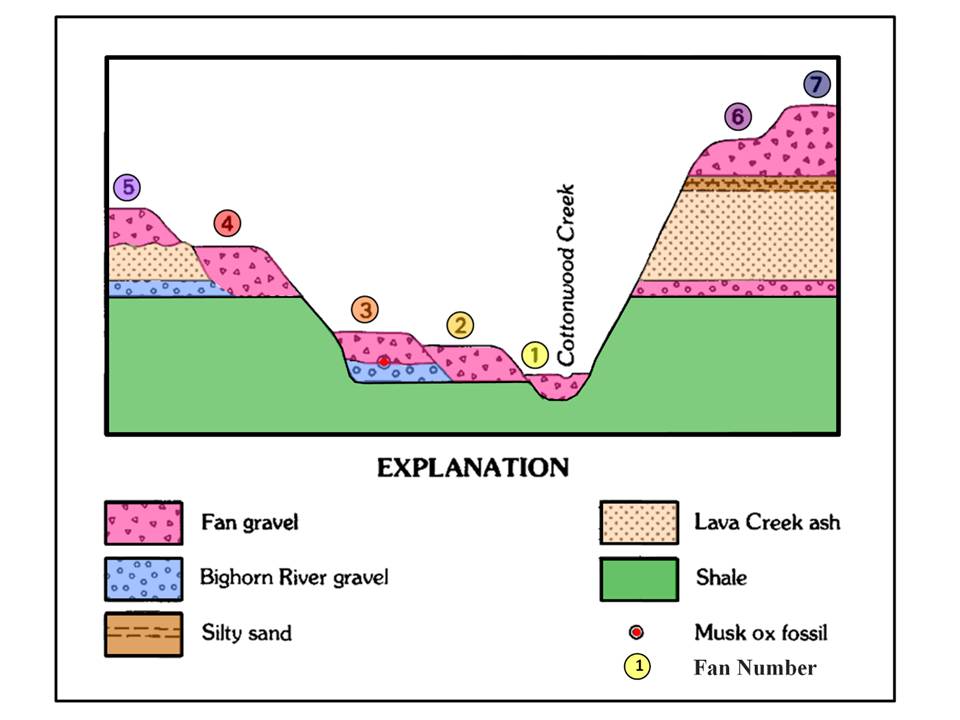

Schematic diagram of surficial deposits along the east side of the Bighorn River in the Cottonwood Creek area.

Image: Reheis, M.C., 1987, Gypsic Soils on the Kane Alluvial Fans, Big Horn County, Wyoming: USGS Bulletin 1590-C, Fig. 4, p.C73. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1590c/report.pdf

Image: Reheis, M.C., 1987, Gypsic Soils on the Kane Alluvial Fans, Big Horn County, Wyoming: USGS Bulletin 1590-C, Fig. 4, p.C73. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1590c/report.pdf

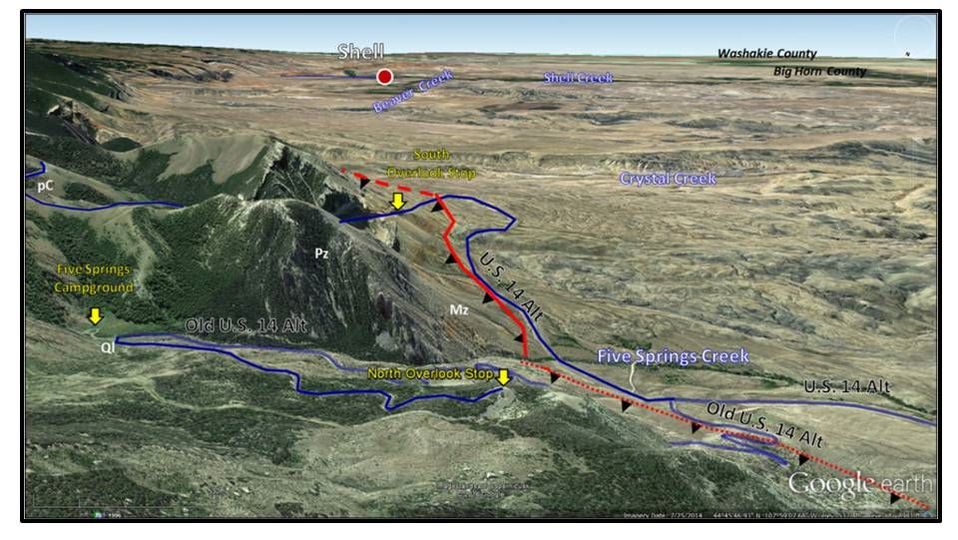

South aerial view of North overlook stop on Old U.S. 14 Alternate. Geologic notation: Ql: Quaternary landslide debris; Mz: Mesozoic age rocks; Pz: Paleozoic age rocks; pC: Precambrian age rocks. Thrust fault: red line with black triangles, solid: cut surface, dashed: buried, dotted: inferred.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

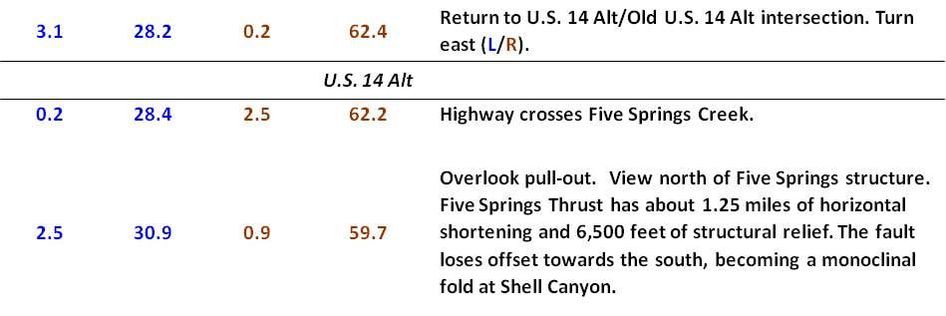

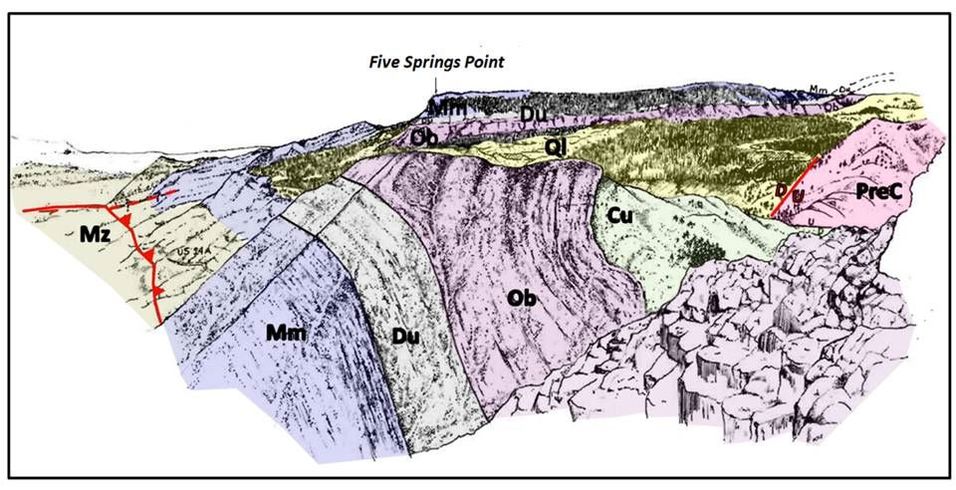

Geologic map of the Five Springs Area. US 14 Alt Road: solid blue line; Faults: Red solid, dashed and dotted lines; Geologic Notation: LK: Lower Cretaceous units, J-LK: Lower Cretaceous and Jurassic units, Tr: Triassic units; M-P: Pennsylvanian and Mississippian units; D-M: Devonian and Mississippian units; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Formation; Cu: undifferentiated Cambrian units; pC: Precambrian basement rock.

Image: After Willis, J.J., 1994, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: Discussion: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 4, Fig. 2, p. 646.

Image: After Willis, J.J., 1994, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: Discussion: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 4, Fig. 2, p. 646.

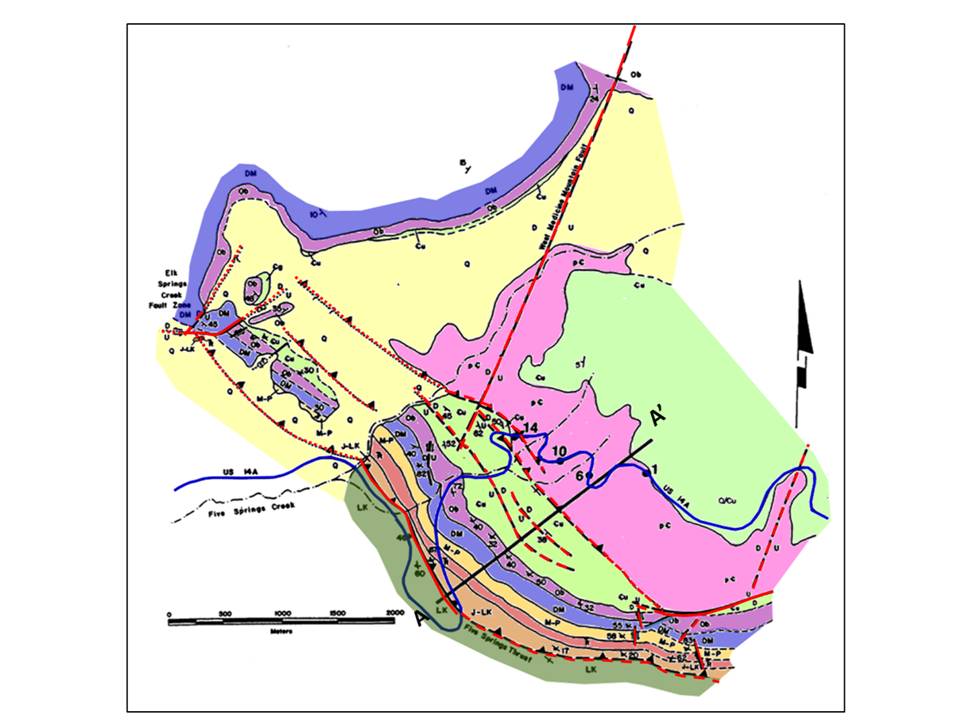

Geologic cross section A-A’ showing the structure at Five Springs. Location of line shown on geologic map above. Geologic notation as above except for the Cambrian units that are differentiate: Cg: Cambrian Gallatin Formation; Cgv: Cambrian Gros Ventre Formation; Cf: Cambrian Flathead Formation.

Image: After Willis, J.J., 1994, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: Discussion: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 4, Fig. 6, p. 650.

Image: After Willis, J.J., 1994, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: Discussion: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 4, Fig. 6, p. 650.

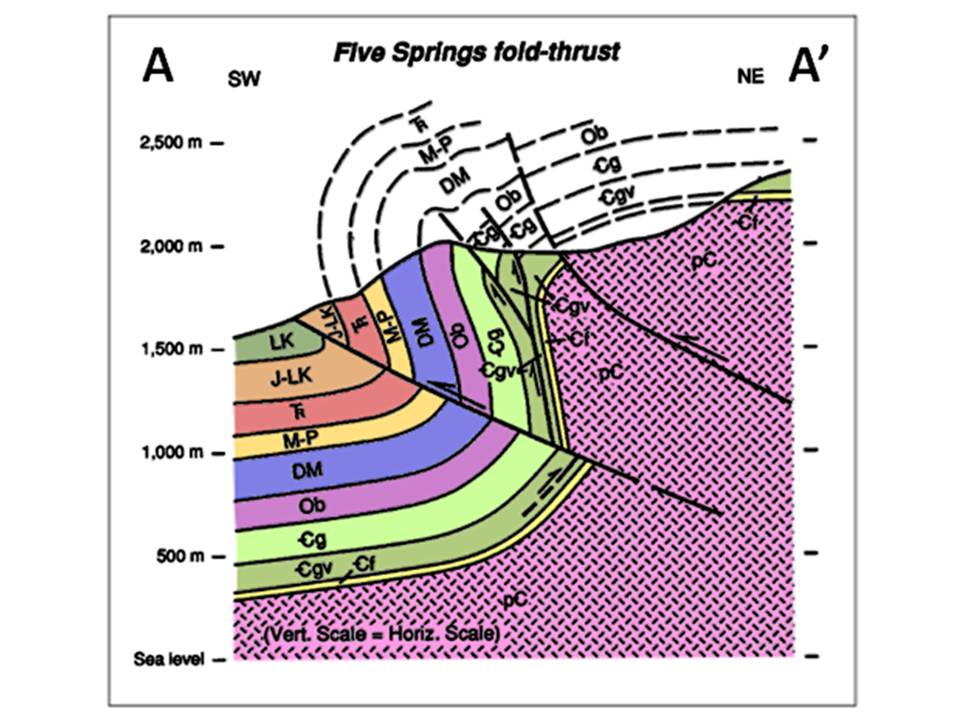

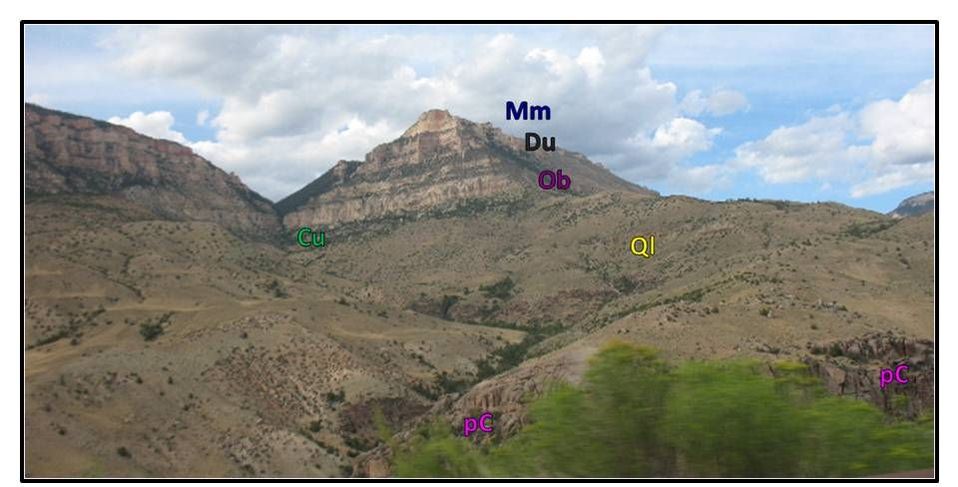

North view sketch of the Five Springs structure. Geologic notation: Ql: Quaternary landslide debris; Mm: Mississippian Madison Formation; Du: undifferentiated Devonian units; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite; Cu: undifferentiated Cambrian units; Pre C: Precambrian basement. Thrust fault: red triangles; Strike-slip fault: red arrow; Normal fault: red “U” (up), “D” (down)

Image: After Hoppin, R.A., 1970, Structural Development of Five Springs Creek Area, Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming: GSA Bulletin, Vol. 81, Fig. 3, p. 2405.

Image: After Hoppin, R.A., 1970, Structural Development of Five Springs Creek Area, Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming: GSA Bulletin, Vol. 81, Fig. 3, p. 2405.

West view sketch showing folded stratigraphic rocks contact with basement. Cambrian Flathead Sandstone is dipping at 52 degrees to the west-southwest at Precambrian basement contact

After Wise, D.U. and Obi, C.M., 1992, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 10, Fig. 6, p. 1592.

After Wise, D.U. and Obi, C.M., 1992, Laramide Basement Deformation in an Evolving Stress Field, Bighorn Mountain Front, Five Springs Area, Wyoming: AAPG Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 10, Fig. 6, p. 1592.

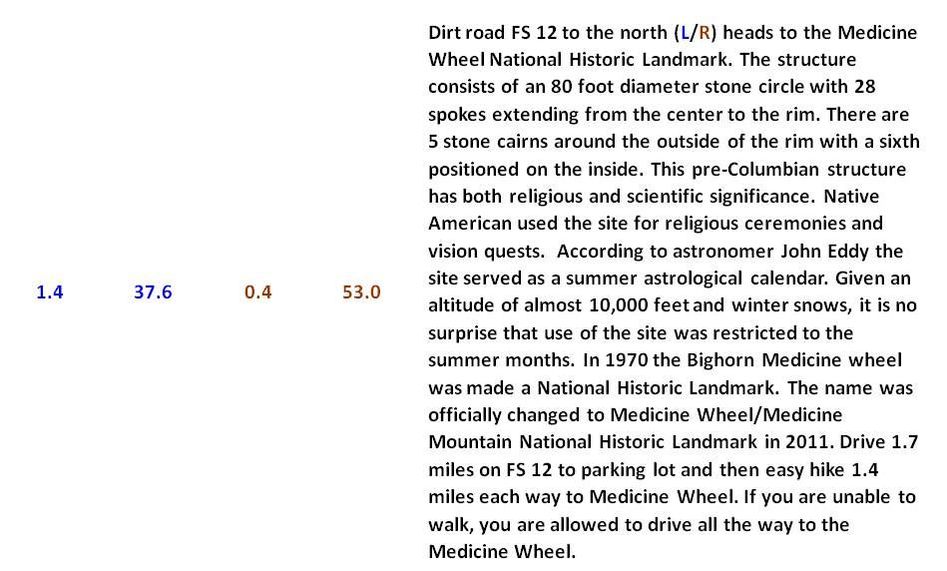

Left: Bighorn Medicine Wheel located atop Medicine Mountain. Right: Diagram showing summer alignments.

Image: Left: U.S. Forest Service Photo, 2008, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/91/MedicineWheel.jpg; Right: Sunrise Magazine, 1998, http://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sunrise/47-97-8/4s-wtst.htm

Image: Left: U.S. Forest Service Photo, 2008, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/91/MedicineWheel.jpg; Right: Sunrise Magazine, 1998, http://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sunrise/47-97-8/4s-wtst.htm

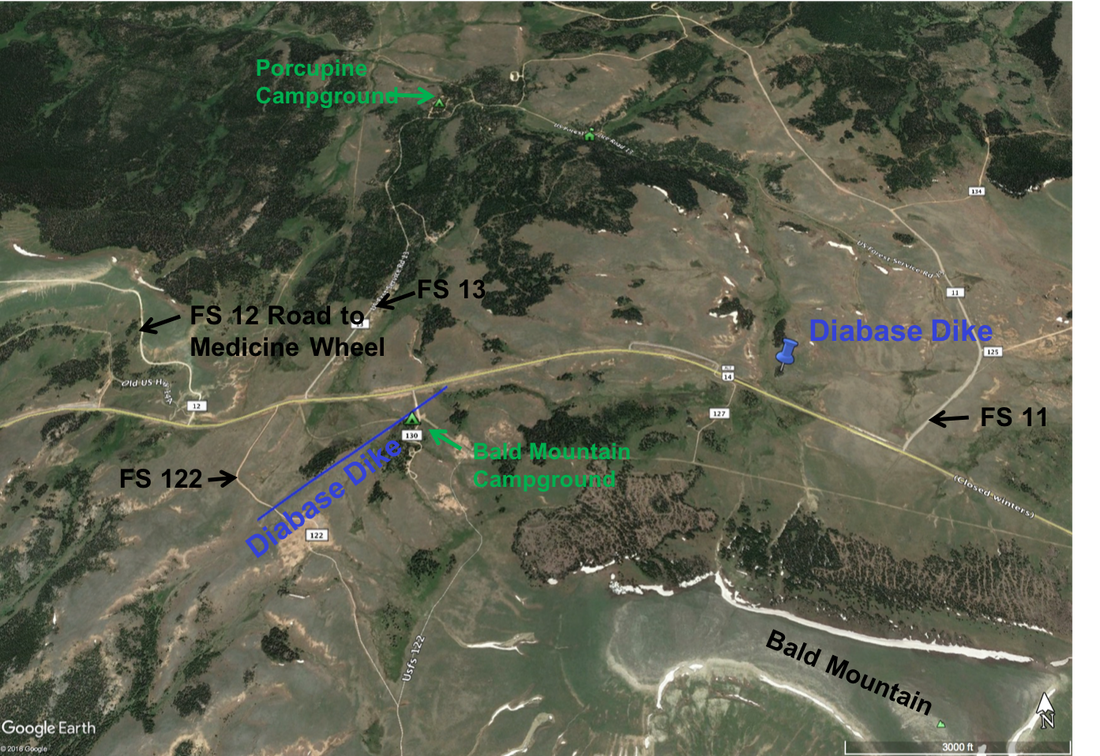

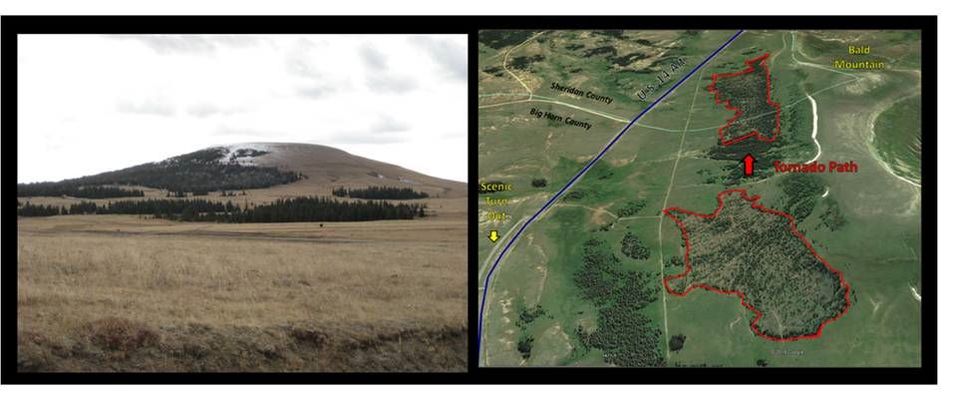

Map of mafic dikes near Bald Mountain campground.

Image by Google Earth

Image by Google Earth

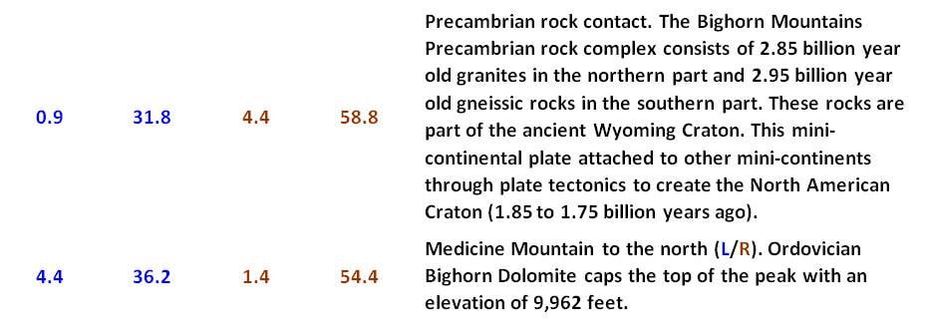

View North and west from scenic pull out. Left: Precambrian outcrop; Right: Medicine Mountain.

Image: Left: chris1073, 2013; Right: tutunaku, 2010

Image: Left: chris1073, 2013; Right: tutunaku, 2010

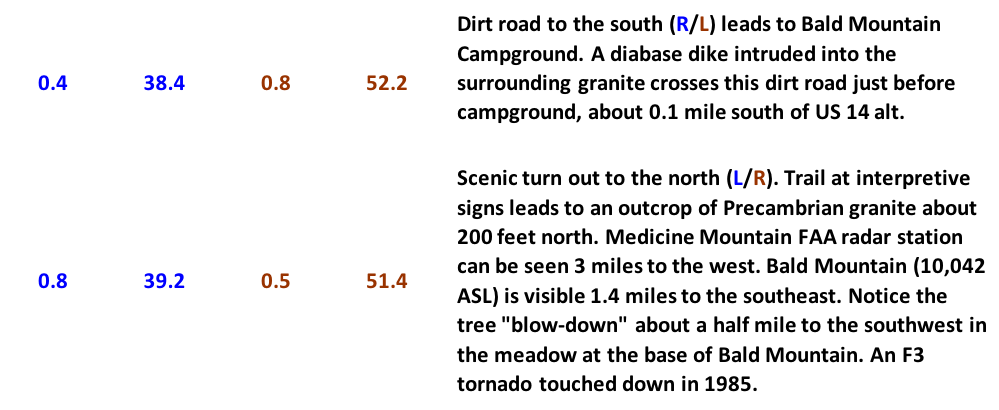

View south from scenic pull out. Left: Bald Mountain outcrop; Right: Bald Mountain tornado site. Area of tree blowdown shown by red dashed line.

Image: Left: musicman82, 2009, http://images.summitpost.org/original/451830.jpg; Right: Google Earth

Image: Left: musicman82, 2009, http://images.summitpost.org/original/451830.jpg; Right: Google Earth

View north from US 14A of diabase dike on right side of hill and granite on left side of hill.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

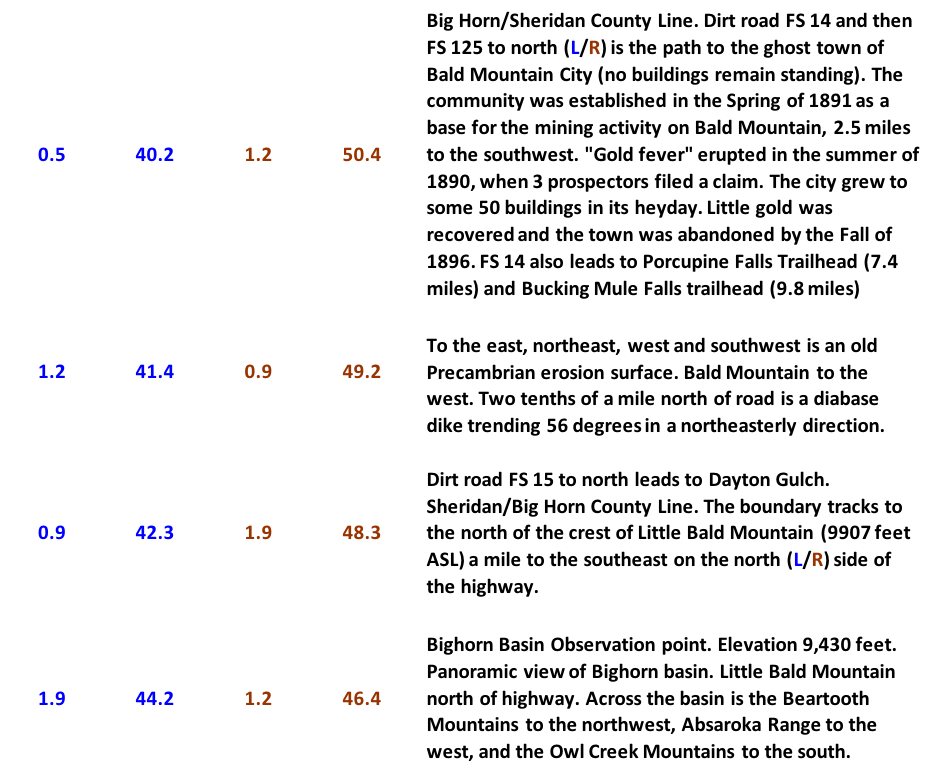

Southwest aerial view at Bighorn Basin Overlook. U.S. 14 Alt is solid blue line. Note the contrast between the relatively flat surface of the Bighorn Mountains and the steeply westward dipping flatirons along the west mountain front.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

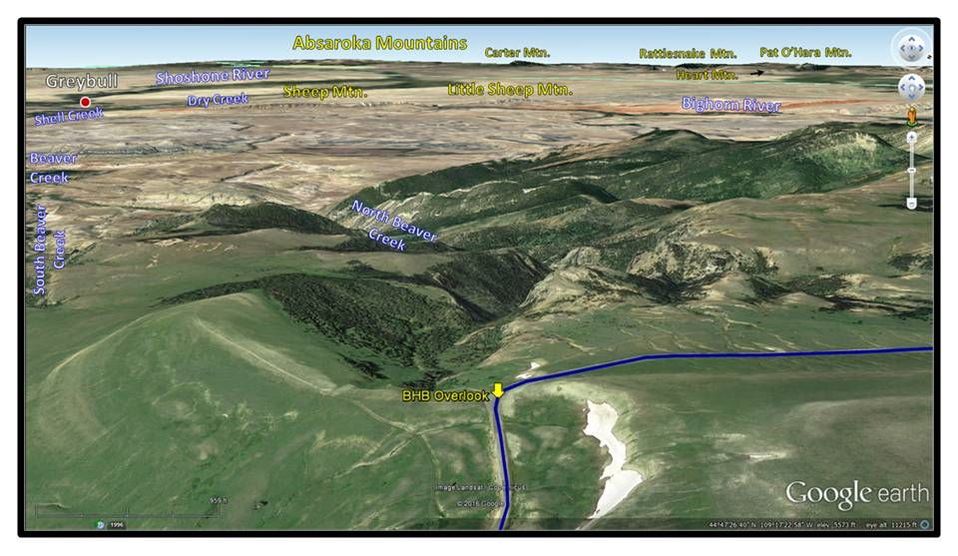

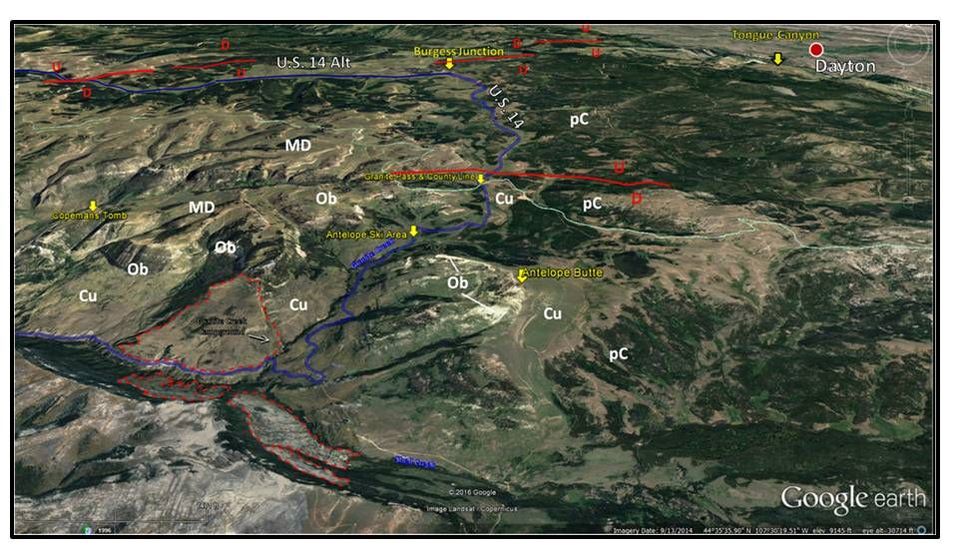

North Aerial View at Bighorn Basin Overlook showing Geology of area. Geologic notation: MD: Mississippian and Devonian units; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite; Cu: undifferentiated Cambrian Formations; pC: Precambrian basement. Location of normal fault shown by solid red line with direction of offset indicated by “U” (up) and “D” (down). This is one of a group of east-north eastern trending normal faults leading to Tongue River Canyon west of Dayton. U.S. 14 Alt is solid blue line.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

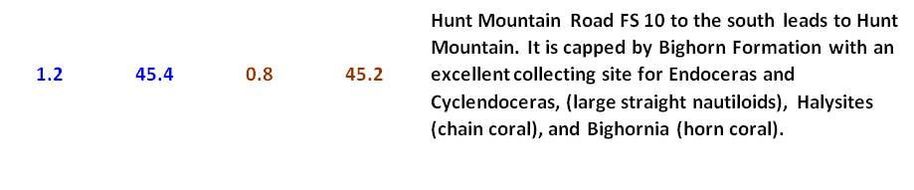

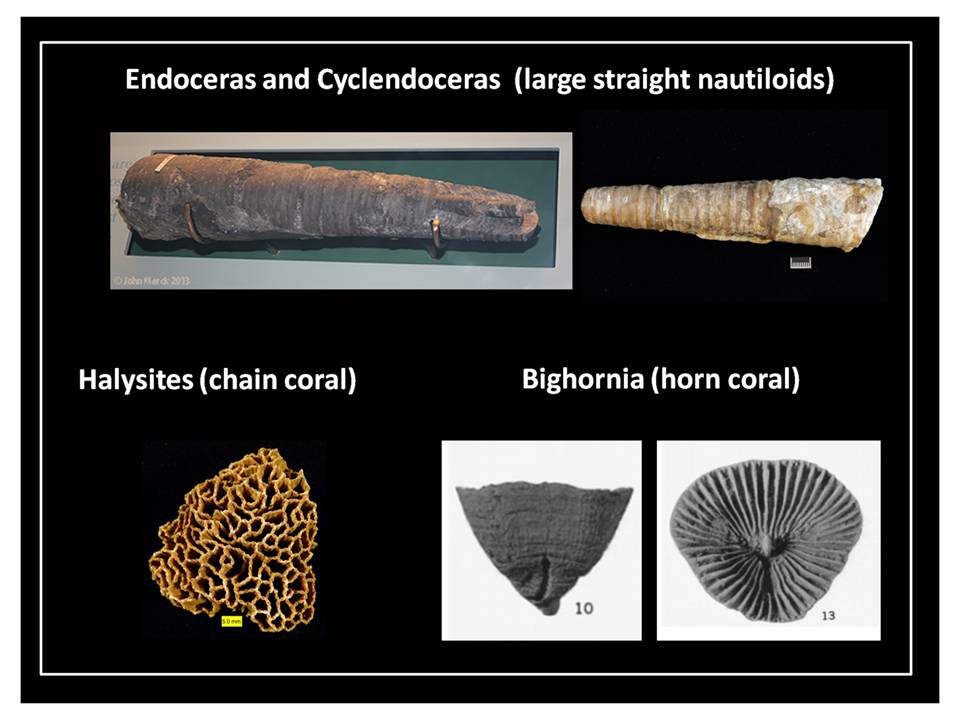

Types of fossils found in The Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite at Hunt Mountain.

Images:

Endocares: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/Endoceras_1.jpg;

Cycledoceras: http://geokogud.info/elm/specimen_image/g1/g1-56.jpg;

Halysites: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/HalysitesSilurian.jpg/220px-HalysitesSilurian.jpg;

Bighornia: Duncan, H., 1957, Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 31, No. 3, Plate 70

Images:

Endocares: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/Endoceras_1.jpg;

Cycledoceras: http://geokogud.info/elm/specimen_image/g1/g1-56.jpg;

Halysites: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/HalysitesSilurian.jpg/220px-HalysitesSilurian.jpg;

Bighornia: Duncan, H., 1957, Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 31, No. 3, Plate 70

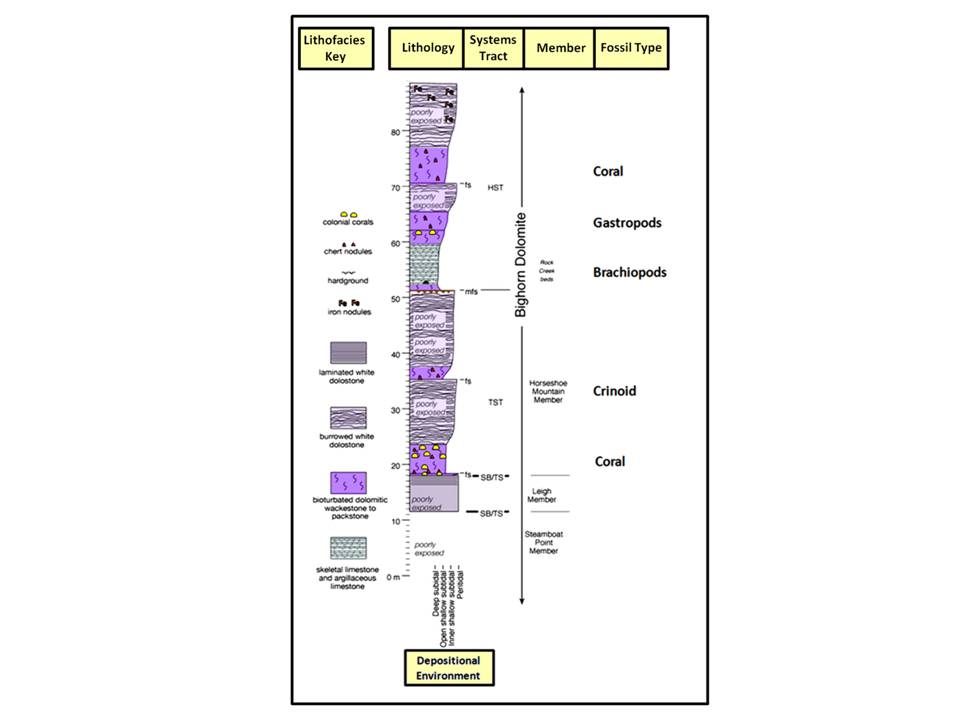

Ordovician Bighorn Formation lithologic column at Hunt Mountain showing stratigraphic position of fossils. Systems Tract Code: fs: flooding surface; mfs: maximum flooding surface; HST: high stand systems tract; SB/TS: sequence boundary/ transgressive surface; TST: transgressive systems tract

Image: After Holland, S.M. and Patzkowsky, S.M., 2009, The stratigraphic distribution of fossils in a tropical carbonate succession: Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite, Wyoming, USA: Palaios, Vol. 24, No. 5; https://www.jstor.org/stable/27670608

Image: After Holland, S.M. and Patzkowsky, S.M., 2009, The stratigraphic distribution of fossils in a tropical carbonate succession: Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite, Wyoming, USA: Palaios, Vol. 24, No. 5; https://www.jstor.org/stable/27670608

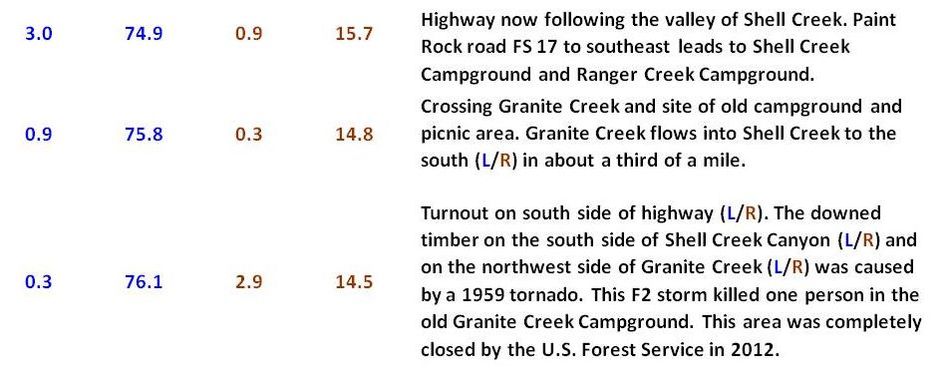

North aerial view of Granite and Shell Creek area showing the bedrock geology. Bighorn Byway shown by solid blue line. Normal fault near Granite Pass is the solid red line with direction of offset indicated by ”U” (up) and “D” (down). Area of tree “blowdown” from 1959 tornado is outlined by dashed red line. Geologic notation: MD: Mississippian and Devonian Formations; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite; Cu: undifferentiated Cambrian Formations; pC: Precambrian basement.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

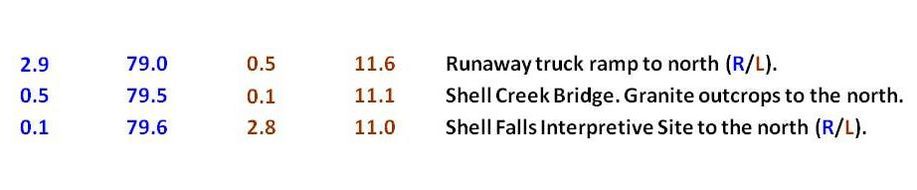

West aerial view of Shell Canyon Area.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

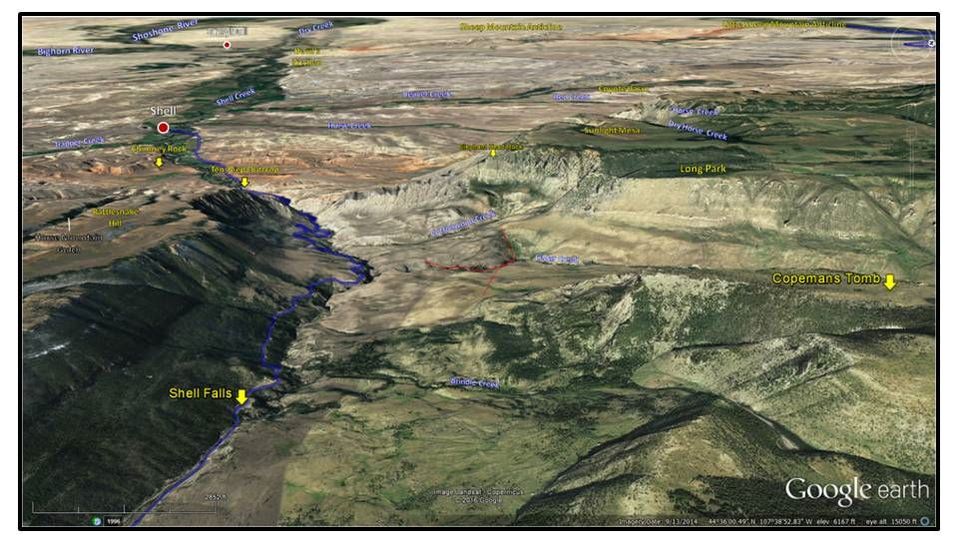

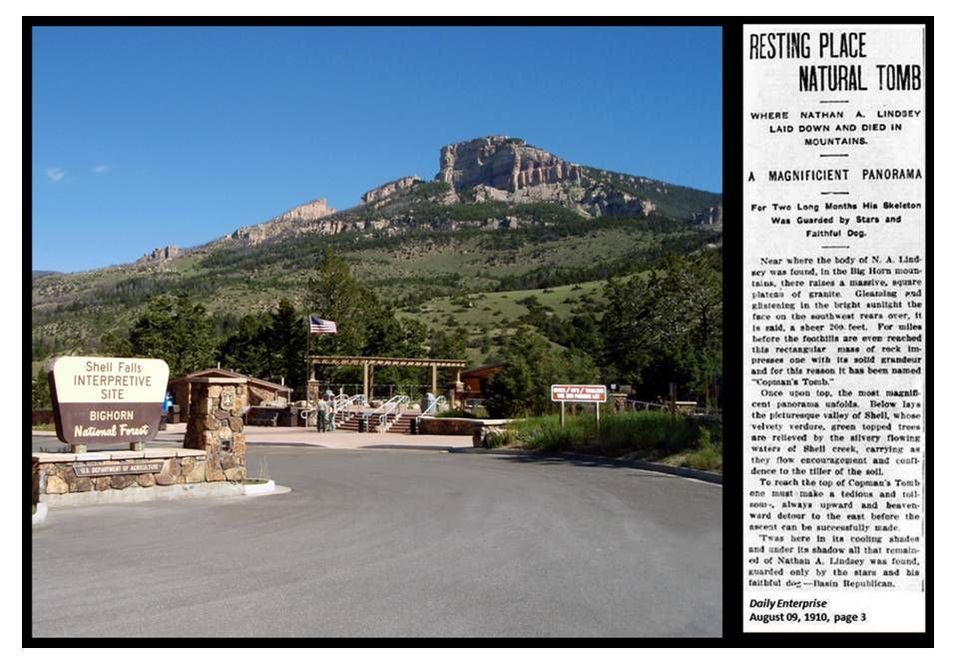

North view of Shell Falls Interpretive Site with Copemans Tomb on the skyline. Wolfgang Robert Copeman was a pioneer sheepman working in the Shell area for which he had a great love. He loved the area so much that he wanted his ashes scattered on one of the peaks. But when he died in 1907, his wife's religious objections to cremation prevented his wishes from being fulfilled. The locals memorialized him by naming his desired resting place Copemans Tomb. However, the peak did serve as a temporary headstone for one Nathan A. Lindsey who went to get the mail and supplies in 1920 and never returned.

Image: https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MEDIA/stelprdb5364725.jpg

Image: https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MEDIA/stelprdb5364725.jpg

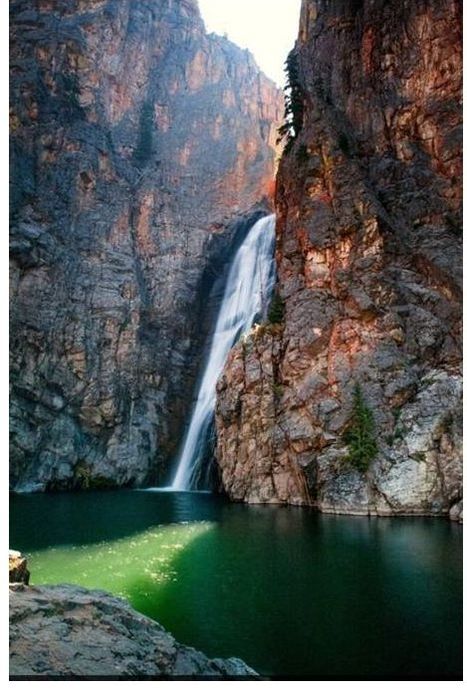

Shell Falls and Creek. Shell Creek has cut a narrow v-shaped canyon in the last million years. The canyon is over 8 miles long and 2,500 feet deep. At the falls Shell Creek drops 120 feet over eroded 2.9 billion year old Precambrian granite. Its maximum flow rate is 3,600 gallons per second. Shell Creek elevation drops from 11,000 feet in the Cloud Peak Wilderness to under 3,800 feet where it flows into the Bighorn River.

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

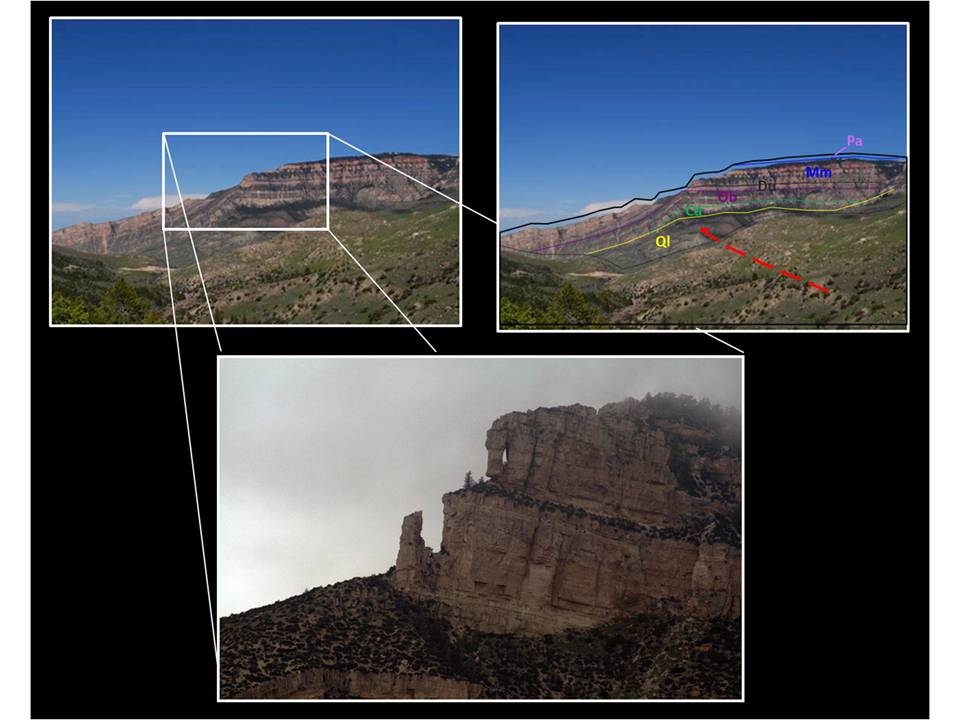

Top Left: Shell Monocline fold is generated by a buried reverse fault. This structure was used to develop the “block uplift model” of Laramide folding. This vertical uplift interpretation was shown to be incorrect by seismic data obtained in the 1980s. Box shows area of enlarged image. Top Right: Geology of monoclinal fold. Buried reverse fault: red dash line. Geologic notation: Ql: Quaternary landslide debris; Pa: Pennsylvanian Amsden Formation; Mm: Mississippian Madison Formation; Du: undifferentiated Devonian formations; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Formation; Cu: undifferentiated Cambrian formations.

Bottom: Elephant Head Rock to the right (northeast) of the monoclinal flexure.

Image: Top Left and Right: After http://www.cco.caltech.edu/~nova/Site/2011_PCC_Geology_Field_Trip_Blog/Entries/2011/6/26_June_24_-_Cody,_Wyoming.html;

Bottom: https://farm3.staticflickr.com/2072/2184995004_d2366eae12_b.jpg

Bottom: Elephant Head Rock to the right (northeast) of the monoclinal flexure.

Image: Top Left and Right: After http://www.cco.caltech.edu/~nova/Site/2011_PCC_Geology_Field_Trip_Blog/Entries/2011/6/26_June_24_-_Cody,_Wyoming.html;

Bottom: https://farm3.staticflickr.com/2072/2184995004_d2366eae12_b.jpg

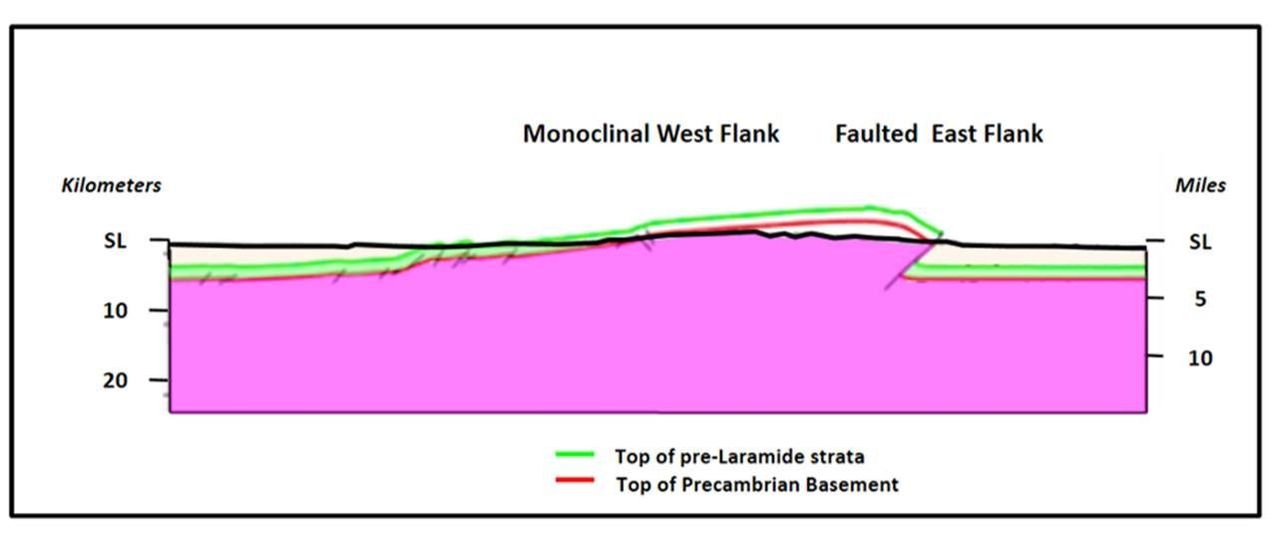

Structure of the Bighorn Mountains Arch. A monocline, such as at Shell Canyon, is formed when the fault does not cut through the stratigraphic section (often called a blind or buried thrust).

Image: After Stone, D. S. (1993), Basement-involved thrust generated folds as seismically imaged in sub-surface of the central Rocky Mountain foreland, in Laramide Basement Deformation in the Rocky Mountain Foreland of the Western United States, edited by C. J. Schmidt, R. B. Chase, and E. A. Erslev, Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am., 280

Image: After Stone, D. S. (1993), Basement-involved thrust generated folds as seismically imaged in sub-surface of the central Rocky Mountain foreland, in Laramide Basement Deformation in the Rocky Mountain Foreland of the Western United States, edited by C. J. Schmidt, R. B. Chase, and E. A. Erslev, Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am., 280

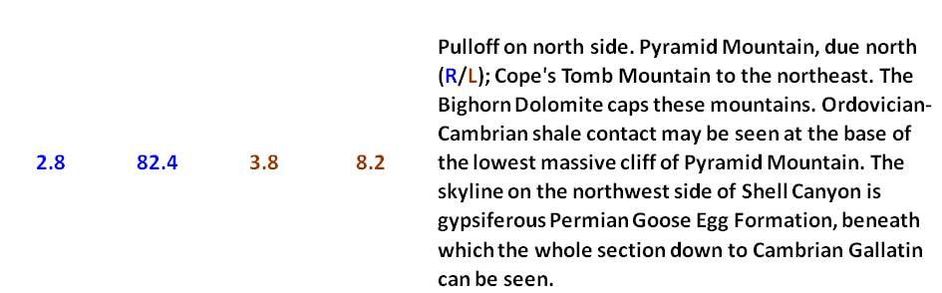

Pyramid Peak to the north. The larger mountain to the right is Sunlight Mesa. The Shell Monocline and Elephant rock are part of this larger topographic feature. Precambrian rock is exposed in the drainage of Cedar Creek Geologic notation: Ql: Quaternary landslide debris; Mm: Mississippian Madison Formation; Du: undifferentiated Devonian units; Ob: Ordovician Bighorn Formation; Ci: undifferentiated Cambrian units; pC: Precambrian basement.

Image: http://travellogs.us/2014%20Logs/Wyoming/WY-11%20Shell%20Canyon/WY-11b%20Shell%20Canyon%20Big%20Horn%20Mts.htm

Image: http://travellogs.us/2014%20Logs/Wyoming/WY-11%20Shell%20Canyon/WY-11b%20Shell%20Canyon%20Big%20Horn%20Mts.htm

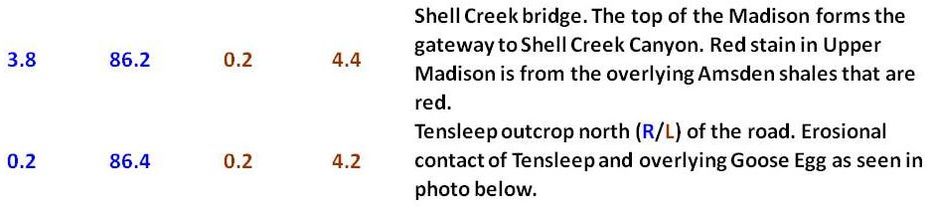

Permian Goose Egg Formation overlying Pennsylvanian erosional unconformity. Post-Tensleep uplift of the Greybull Arch to the North of this area lead to the removal of almost the entire Upper Tensleep at this location. The sandstone bed at the right of the outcrop is eroded a short distance to the left. The thin purple unit just beneath this sandstone is the marker bed at the top of the Lower Tensleep. Solid red line marks the Permian-Pennsylvanian unconformity.

Image: After Bentley, C., 2011, Mountain Beltway: AGU Blogosphere, http://blogs.agu.org/mountainbeltway/2011/06/27/goose-egg-tensleep-contact/

Image: After Bentley, C., 2011, Mountain Beltway: AGU Blogosphere, http://blogs.agu.org/mountainbeltway/2011/06/27/goose-egg-tensleep-contact/

Chimney Rock, known as “The Guardian of the Canyon.”

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

End of Roadlog

The geologic story recorded in the rocks and the awesome beauty of the mountain landscape of canyons, meadows, streams, falls and towering peaks is reason enough to make this trip. But on top of that, there is the human story of Native Americans, trappers, prospectors, ranchers, farmers, outlaws and entrepreneurs whose lives still echo in the Bighorns.

The geologic story recorded in the rocks and the awesome beauty of the mountain landscape of canyons, meadows, streams, falls and towering peaks is reason enough to make this trip. But on top of that, there is the human story of Native Americans, trappers, prospectors, ranchers, farmers, outlaws and entrepreneurs whose lives still echo in the Bighorns.

Things To Do at Bighorn Mountain Byways

Our recommendations are hikes to Medicine Wheel, Porcupine Falls, Bucking Mule Falls and Falling Block, and rock hunting for "leopard rock". Two additional scenic quick stops worth the time are Five Springs Campground/Falls and Shell Falls. There is a short hike to see the falls at Five Springs Campground and there is a short hike to see Shell Falls. The best months to visit are June through mid-October. Highway US 14A closes for the winter, usually in November and opens again by the Memorial Day weekend. US 14 stays open for the winter.

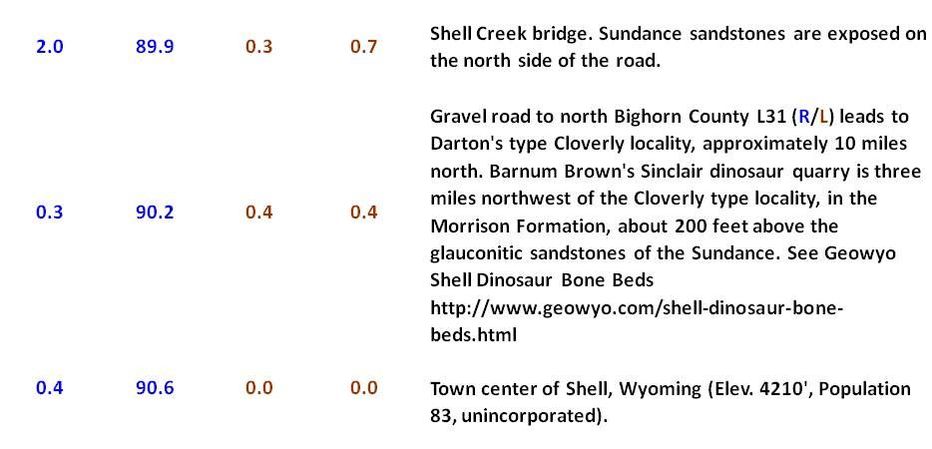

Medicine Wheel

An easy hike of 2.8 miles total roundtrip along a road that takes about an hour of hiking time. It is an out and back with slight elevation gain. If you have a disability that prevents you from walking to the site, you are allowed to drive. The Medicine wheel is 80 foot in diameter and 245 foot in circumference. It has 28 radiating spokes that match the number of days in a lunar month. There are six cairns along the outer edge of the wheel that correspond to the rising and setting of the summer solstice sun and three bright stars. It is believed to be about 700 years old and is still used today for ceremonies, vision quests, meditation and prayer. Be respectful of this Native American sacred site. Great views! Directions: At 37.6 miles on roadlog, turn north on FS 12 (purple route on Google Map below), a dirt road fine for passenger vehicles, 1.3 miles cattle guard, 1.7 miles parking lot at Medicine Wheel trailhead.

Porcupine Falls

A short, but steep hike of one mile total roundtrip that takes about an hour of hiking time. It is an out and back with a 450 foot elevation descent and climb out. You won’t be disappointed by these falls that cascade 200 feet into a beautiful pool surrounded by Precambrian cliffs. To the right of the falls is a smaller cascade issuing from a tunnel that gold miners dug in the early 1900’s to divert the water flow. Directions: At 38.0 miles on roadlog, turn north on FS 13 (green route on Google Map below), a dirt road fine for passenger vehicles, 1.7 miles Porcupine Campground, 1.9 miles cross creek, 2.0 miles road forks, stay left on FS 13, 2.2 miles road forks take left on FS 133, 2.4 miles Jaws trailhead on left, 3.5 miles stop sign turn left on FS 14 (blue route on Google Map below), 7.9 miles turn left on FS 146, this short section is rough and potholed (walk it if you have a car), 8.2 miles remains of old log cabin on right and parking area for Porcupine Falls trailhead.

Porcupine Falls

Image by Lori Trembath

Image by Lori Trembath

Bucking Mule Falls

A hike of 4.7 miles total roundtrip with a slight elevation change that takes about two hours of hiking time. The hike takes you to an overlook with good views of Devils Canyon and the falls from a distance. Directions: Follow directions to Porcupine Falls, but continue at 7.9 miles straight on FS 14 (red route on Google Map below) another 2.4 miles and reach Bucking Mule Falls trailhead at 10.3 miles. Dirt road is fine for passenger vehicles.

Routes to trailheads for Medicine Wheel (purple), Porcupine Falls (green & blue), Bucking Mule Falls (red), and Five Springs Campground (yellow)

Image by Google Earth

Image by Google Earth

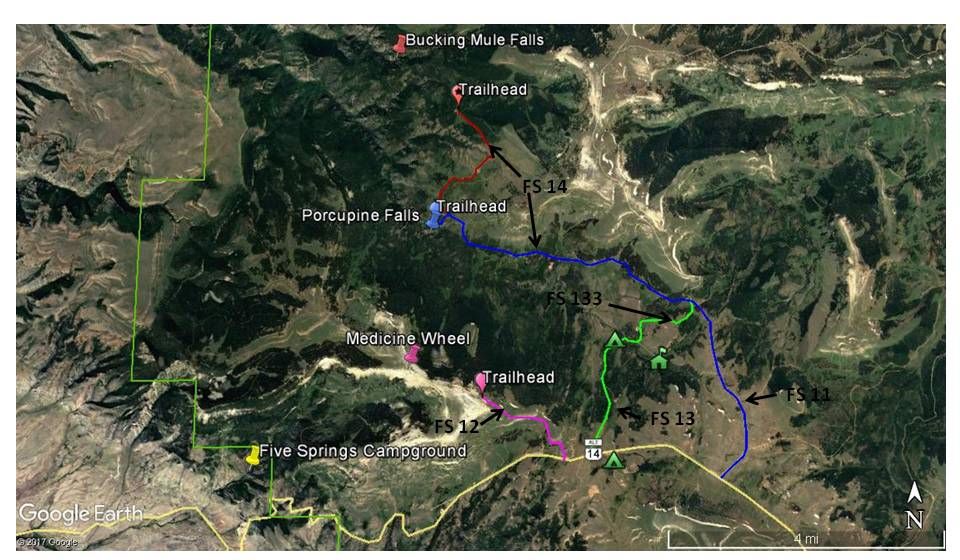

Leopard Rock near Burgess Junction

This attractive igneous rock is called “leopard rock” due to the spotted appearance of large white plagioclase crystals in a dark gray fine-grain mafic groundmass. Plagioclase crystals are concentrated in the central portions of these diabase dikes due to flow differentiation (Stephen Harlan, 2005 Poster GSA Conference pdf). An outcrop of “leopard rock” on the Forest Service can be accessed via a high-clearance 4WD rough dirt road north of Burgess Junction. Directions (see map below): On US 14A, about two tenths of a mile west of the junction of US 14 and US 14A at Burgess Junction, take FS 15 north, 0.2 miles Wyoming Department of Transportation Office & cattle guard, 1.1 miles North Tongue Campground on left, 1.3 miles Burgess Picnic Ground on right, 1.6 miles take right fork in road, FS 163 to Burgess Work Center, 1.9 miles Burgess Ranger Station, 2.0 miles turn left on FS 166 dirt road to North Tongue River Trail (4WD high clearance vehicle needed from this point), 2.1 miles cattle guard, 2.7 miles fence line, 3.2 miles park vehicle just before private cabins. Walk downhill past private cabins toward North Fork of Tongue River, after last cabin and last barb wire fence, turn right and follow fence line slightly uphill for about 100 yards to small quarry pit with “leopard rock”. Be very careful of loose rocks in the walls of this pit. Alternatively, continue downhill a short distance past last cabin to flat area, turn right and walk to the North Fork of Tongue River where there is an outcrop of “leopard rock” on both sides of the river. Please be respectful of the private cabins and do not trespass.

Map to leopard rock diabase dike outcrop and small quarry near Burgess Junction.

Image by Google Earth

Image by Google Earth

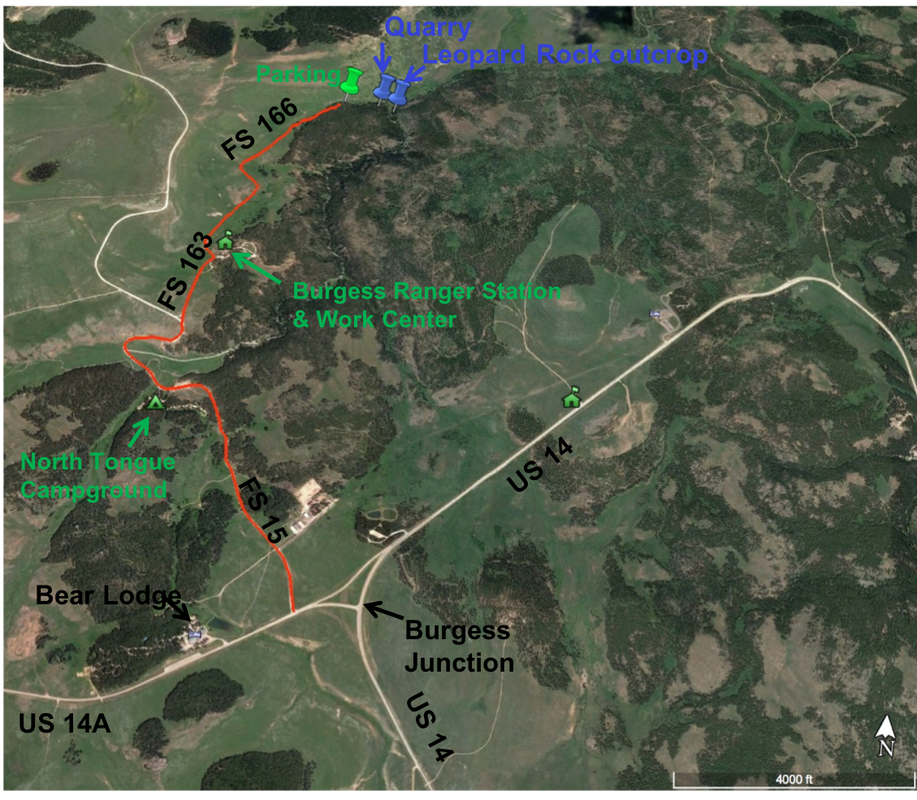

Falling Block near Burgess Junction

Falling Block about four miles south-southwest of Burgess Junction

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

The Falling Block is an unusually large, intact cube of Ordovician Bighorn Dolomite that broke off the adjacent cliff and slid or tumbled to its resting spot on a slope of Cambrian Gallatin shale and limestone. About 50 foot tall, it is amazing that one cohesive block of sedimentary rock can exist without significant bedding planes or fractures. The rock texture is mottled. It was intensely burrowed soon after deposition and prior to cementation. This burrowing reduced sedimentary bedding planes and may also have prevented significant vertical fractures from later developing. Of side interest are the attractive flat pebble conglomerate limestone rocks found along the hike and at Falling Block. These rocks are common in the Cambrian Gallatin and are thought to be caused by a violent storm ripping up the soft mud in shallow water, rounding the clasts, and depositing them in a chaotic conglomerate.

Cambrian Gallatin Limestone flat pebble conglomerate near Falling Block

Image by Mark Fisher

Image by Mark Fisher

Directions to Falling Block: located in the N1/2, NW1/4, Sec 26, T55N & R89W, 44°43'16.2", -107°32'59.8" or 44.72117°, -107.5499°, about four miles south-southwest of Burgess Junction above Willow Creek in a general area called Bear Rocks. There is no trail to The Falling Block other than some weak game trails and climber trails. A topo map and screen shots of the area on Google Earth would be helpful for navigating. On US 14A, 1.7 miles west of junction US 14 and US 14A at Burgess Junction, take FS 159 south 3 miles until the road ends. This is a soft dirt road with ruts that should only be driven during dry conditions with a high clearance 4WD vehicle. It runs parallel to Willow Creek with the creek on the left (east) and private summer cabins on the right (west). About 100 yards before the end of the road, a spring has made the road a muddy morass and it is best to turn around and park at this point. The walk is one mile each way with an elevation change of 600 vertical feet. Walk to the end of the road where the Forest Service has blocked vehicle travel with boulders and a ditch. Cross Willow Creek, climb the steep hill to the east and then walk parallel to the creek to the south through meadows bordered by trees on the uphill side. You will cross about three small spring-fed creeks. Just after crossing the largest of the small creeks at about 0.8 miles from the vehicle, head uphill through one of gaps in the forest to reach the scree slope with large boulders. Falling Block is at the bottom of this large scree slope just uphill from the tree cover.

Map to Falling Block near Burgess Junction

Image by Google Earth

Image by Google Earth

The material on this page is copyrighted