Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (2 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

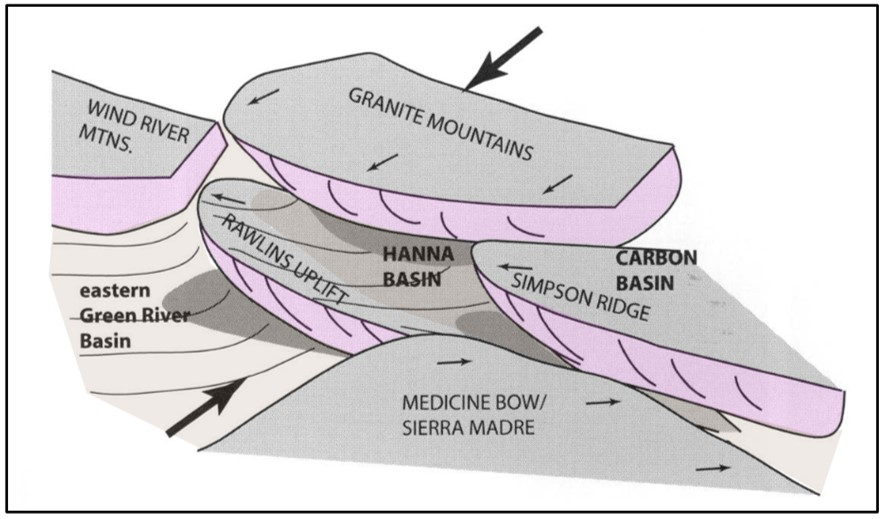

Laramide Structure separating The Great Divide Basin and Hanna Basin near historic Fort Steele and the railroad town of Rawlins.

The Rawlins Uplift is the structural arch that separates the Greater Green River Basin (west) from the Hanna Basin (east). The feature was named after the nearby town of Rawlins. Rawlins was originally called Rawlins Springs and named for General John A. Rawlins, commander of the troops protecting the Union Pacific parties surveying the route of the Transcontinental Railroad and President Grant’s Secretary of War. In 1868, after drinking from a spring Gen. Rawlins remarked “If anything is ever named after me, I want it to be a spring.” The spring and town commemorate the General’s wish.

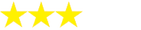

Northwest view of Rawlins Uplift area. Rawlins is at the southeast corner of the uplift where the bounding fault changes orientation from westward-southwestward movement to south-directed thrusting. It is at this corner that maximum offset of the Precambrian basement occurs. Rawlins Peak, at 7, 804 foot elevation, is the highest point of the uplift.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

Northeast View of Rawlins area from I-80.

Image: After City of Rawlins webpage, 5430 & 5431 montage; http://www.rawlinswy.org/SlideShow.aspx?AID=3&AN=City%20Photos

Image: After City of Rawlins webpage, 5430 & 5431 montage; http://www.rawlinswy.org/SlideShow.aspx?AID=3&AN=City%20Photos

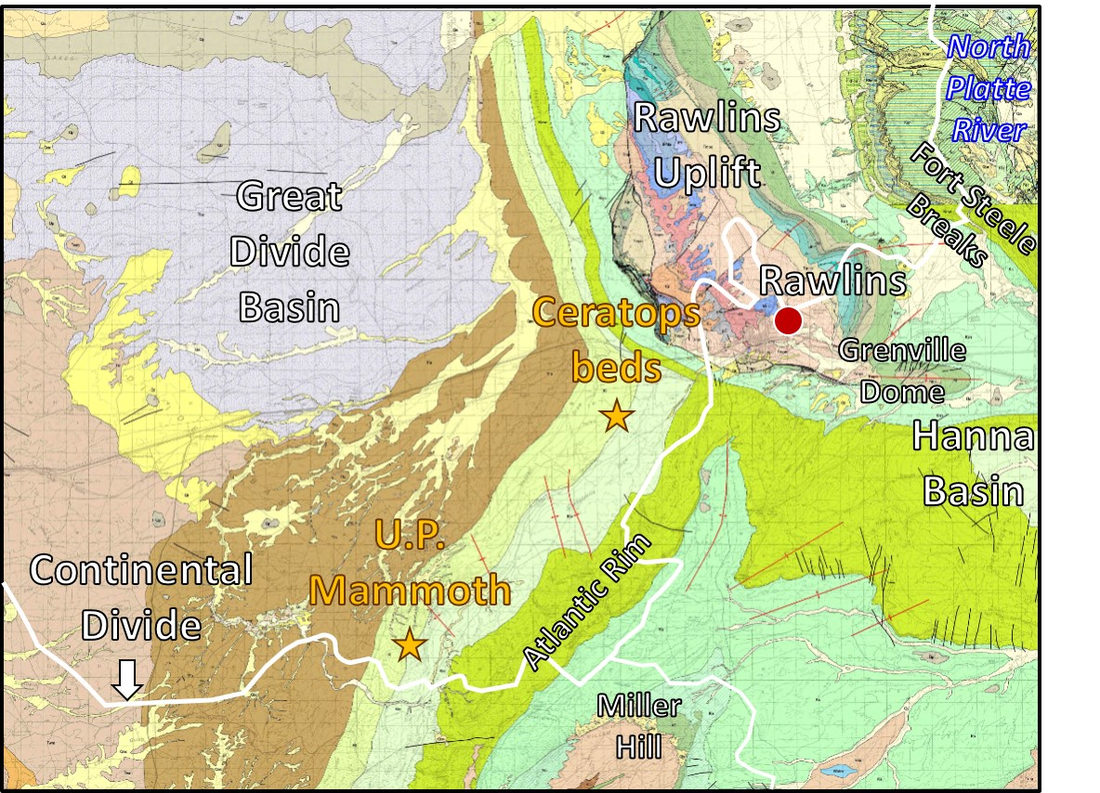

Rawlins Uplift on the eastern margin of the Great Divide Basin, Greater Green River Basin. Eastern boundary of the Continental Divide shown by red line. Rawlins, Wyoming is located at the southeastern margin of the Great Divide Basin. Fort Steele Is on the west bank of the North Platte River, 15 miles east of Rawlins. Light blue dot dash line is approximate path of the first geologic survey of Hayden across Wyoming, 1868. The majority of the survey’s livestock was stolen while camped south of Rawlins. Most of the team returned to Laramie while Hayden and one other continued onward into the Great Divide Basin. Gas well locations along the Wamsutter Arch can be seen on the left of the image. Gold stars mark sites of interest.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

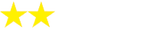

U.P. Mammoth Site

The Rawlins area south of the Granite Mountains was the ancestral home to the Ute People. The Shoshone lived to the north in the Wind River Basin. The Arapahoe and Cheyenne inhabited land east of the Medicine Bow Mountains and the Rawlins Uplift. In 1960, mammoth remains, and Clovis artifacts were discovered 24 miles southwest of Rawlins in alluvium of Chicken Spring Creek. The Mammoth skull is radiometrically dated at 11,500 before present. The remains contain one of the most complete Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) skulls discovered. The fossil is on display at the Geology Museum, University of Wyoming, Laramie.

U.P. Mammoth site geologic excavation map, Chicken Spring Creek valley cross section, and stratigraphic column of Holocene surficial deposits.

Image: After C. Vance Haynes, C.V., Jr., Surovell, T.A, Hodgins, G.W.A., 2013, The U.P. Mammoth Site, Carbon County, Wyoming, USA: More Questions than Answers: Geoarchaeology 28 (2), Fig. 2, p. 101, Fig. 3 & 4, p. 102; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261546455_The_UP_Mammoth_site_Carbon_County_Wyoming_USA_More_questions_than_answers.

Image: After C. Vance Haynes, C.V., Jr., Surovell, T.A, Hodgins, G.W.A., 2013, The U.P. Mammoth Site, Carbon County, Wyoming, USA: More Questions than Answers: Geoarchaeology 28 (2), Fig. 2, p. 101, Fig. 3 & 4, p. 102; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261546455_The_UP_Mammoth_site_Carbon_County_Wyoming_USA_More_questions_than_answers.

Columbia mammoth skull from the U.P. discovery on display at the University of Wyoming Geology Museum. It’s easy to imagine early Greek and Roman civilizations believing in a race of giant cyclops from discovery of a mammoth skull (image on left). U.P. Mammoth site is located at northwest 1/4 of southeast 1/4 of southeast 1/4, Section 1, Township 18 North, Range 91 West.

Image: Left: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jsjgeology/32213698720; Right: Billings Gazette, Dec. 19, 2009, from UW News Service; https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/wyoming/mammoth-skull-from-rawlins-joins-international-tour/article_e1d689c2-ed1e-11de-b7aa-001cc4c03286.html.

Image: Left: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jsjgeology/32213698720; Right: Billings Gazette, Dec. 19, 2009, from UW News Service; https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/wyoming/mammoth-skull-from-rawlins-joins-international-tour/article_e1d689c2-ed1e-11de-b7aa-001cc4c03286.html.

Ceratops Beds

Early geologic reports called a fossil bearing unit the “Ceratops beds.” Today this unit is known to be the Latest Cretaceous Lance Formation that is overlain by the shales of the Paleocene Fort Union Formation. The Lance Formation consists of fluvial deposits that were eroded from the Sevier Highlands of western Wyoming. The contact between the Lance and Fort Union formations marks the Cretaceous – Tertiary boundary (K-T extinction level). The Lance is also the first formation that shows evidence for the onset of the Laramide tectonism in this part of Wyoming. The first Wyoming Ceratop (Marsh nomenclature) was reported by Cope from the Ceratops beds (Lance Formation) near Black Buttes and Bitter Creek, east flank, Rock Springs Uplift in 1872. Cope called the discovered remains Agathaumas sylvestris. The first Triceratops skull in Wyoming was discovered by J. B. Hatcher in the Lance Formation northwest of Lusk (Powder River Basin) in 1888. The species had been misidentified by Marsh the year before from a partial discovery in Colorado as a Pliocene bison (Bison alticornis). Triceratops bones are found in Upper Cretaceous Medicine Bow Formation (Lance Formation equivalent) in the adjacent Hanna Basin. Wyoming’s dinosaurs first gain notoriety when UnionPacific Railroad employees discovered and reported abundant dinosaur bones in the hills of Como Bluff to Marsh (Yale College, New Haven, Connecticut) in 1877. Both Marsh and his rival Cope (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) had teams working in the area within a year. Cope’s suggestion to rename Marsh’s Ceratopsian group (1890) to his Agathaumid group (1891), furthered the emerging hostilities of the bone wars between these two men and their collecting teams (1872-1892; see https://www.geowyo.com/como-bluff.html). Wyoming designated the Triceratops the official state dinosaur in 1994.

Ceratops beds” and U.P. Mammoth site aerial image, geologic map and index. Continental Divide shown by white line.

Image: Top: Google Earth; Bottom two: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf

Image: Top: Google Earth; Bottom two: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf

Left: Charles Knight’s 1897 interpretation of Cope’s Agathaumas (Greek for “great wonder”). Right: Knight’s 1901 reconstruction of Triceratops

Image: Left: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agathaumas#/media/File:Agathaumas.jpg; Right: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knight_Triceratops.jpg.

Image: Left: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agathaumas#/media/File:Agathaumas.jpg; Right: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knight_Triceratops.jpg.

Sharktooth Ridge and Grenville Dome at Sinclair

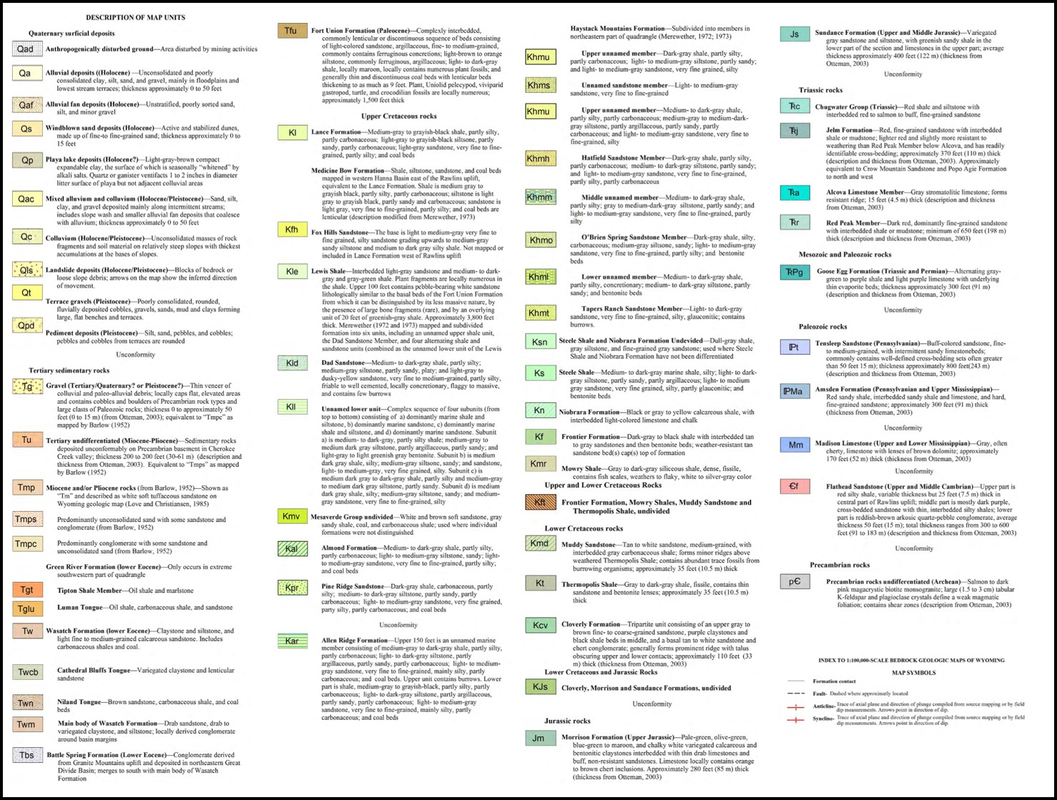

The Cretaceous units surrounding the Rawlins uplift contain abundant ammonite and other marine invertebrates. A ridge just north of Sinclair contains shark teeth. (https://hikinginthelight.us/2019/09/rockhounding-locations-in-wy-mt-ut-rough-draft/). Concretions within shale beds of the Frontier on Grenville Dome contain ammonites, shark teeth and other marine organisms (Lee, W.T., Stone, R.W., Gale, H.S. and others, 1916 Guidebook of the western United States: Part B, Overland Route, with a side trip to Yellowstone Park: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 612, p. 63;https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0612/report.pdf).

Sinclair had its beginning as a water pumping station for the railroad. The Rawlins municipal water had too a high a mineral level content to be used for boiler water. Fresher water was pumped 15 miles with a rise of 236 feet from the North Platte River at Fort Steele. The station was named Grenville after the chief railroad engineer, Grenville Dodge. In 1922, an oil refinery was built, and the Denver based company took the first three letters from their trade name to call the town Parco (Producers and Refiners Corporation). Sinclair Refinery purchased the refinery and company town in 1934 during the Great Depression. The town was renamed Sinclair. The structural dome south of town maintains the Grenville name.

Sinclair had its beginning as a water pumping station for the railroad. The Rawlins municipal water had too a high a mineral level content to be used for boiler water. Fresher water was pumped 15 miles with a rise of 236 feet from the North Platte River at Fort Steele. The station was named Grenville after the chief railroad engineer, Grenville Dodge. In 1922, an oil refinery was built, and the Denver based company took the first three letters from their trade name to call the town Parco (Producers and Refiners Corporation). Sinclair Refinery purchased the refinery and company town in 1934 during the Great Depression. The town was renamed Sinclair. The structural dome south of town maintains the Grenville name.

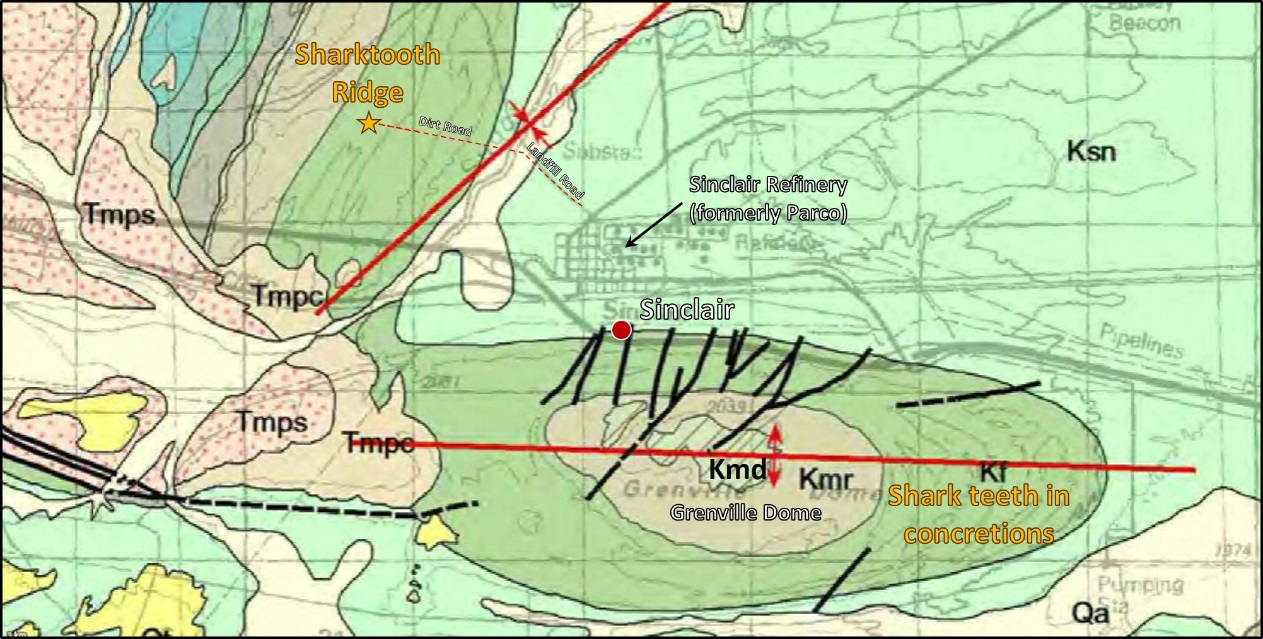

Sharktooth Ridge fossil site aerial image, refineries in former Grenville water pumping station, and geologic map. The fossil site is on private land in southeast 1/4 of northeast 1/4 Section 18, Township 21 North, Range 86 West. The east end of Grenville Dome in section 26 is public BLM land, but shark teeth and vertebrate fossils (example: fish & dinosaur bones) can not be collected on federal land. You may collect invertebrate fossils on federal land (example: ammonites). Geologic notation shown on index above.

Image: Top: Google Earth; Middle Left: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/lincoln3a.html; Middle Right: McGilvray, B., Jr., 2011; https://www.flickr.com/photos/n8myc/6738125203; Bottom: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

Image: Top: Google Earth; Middle Left: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/lincoln3a.html; Middle Right: McGilvray, B., Jr., 2011; https://www.flickr.com/photos/n8myc/6738125203; Bottom: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

West view of Grenville Dome, Sinclair, Wyoming. Abbreviations from youngest to oldest: UPRR = Union Pacific Railroad, Ksn = Cretaceous Steele and Niobrara Formations undivided, Kf = Cretaceous Frontier Formation, Kmr = Cretaceous Mowry Shale, and Kmd = Cretaceous Muddy Sandstone.

Image: After https://slideplayer.com/slide/7622166/ .

Image: After https://slideplayer.com/slide/7622166/ .

Union Pacific Railroad

1915 Union Pacific route map from Grenville to Red Desert station displaying topography and geology.

Image: After Lee, W.T., Stone, R.W., Gale, H.S. and others, 1916 Guidebook of the western United States: Part B, Overland Route, with a side trip to Yellowstone Park: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 612, Sheet No. 11, p. 68; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0612/report.pdf.

Image: After Lee, W.T., Stone, R.W., Gale, H.S. and others, 1916 Guidebook of the western United States: Part B, Overland Route, with a side trip to Yellowstone Park: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 612, Sheet No. 11, p. 68; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0612/report.pdf.

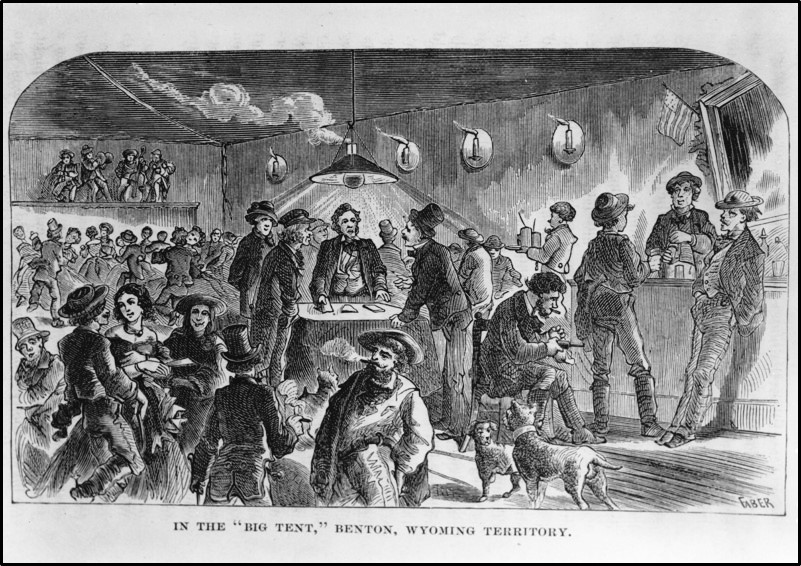

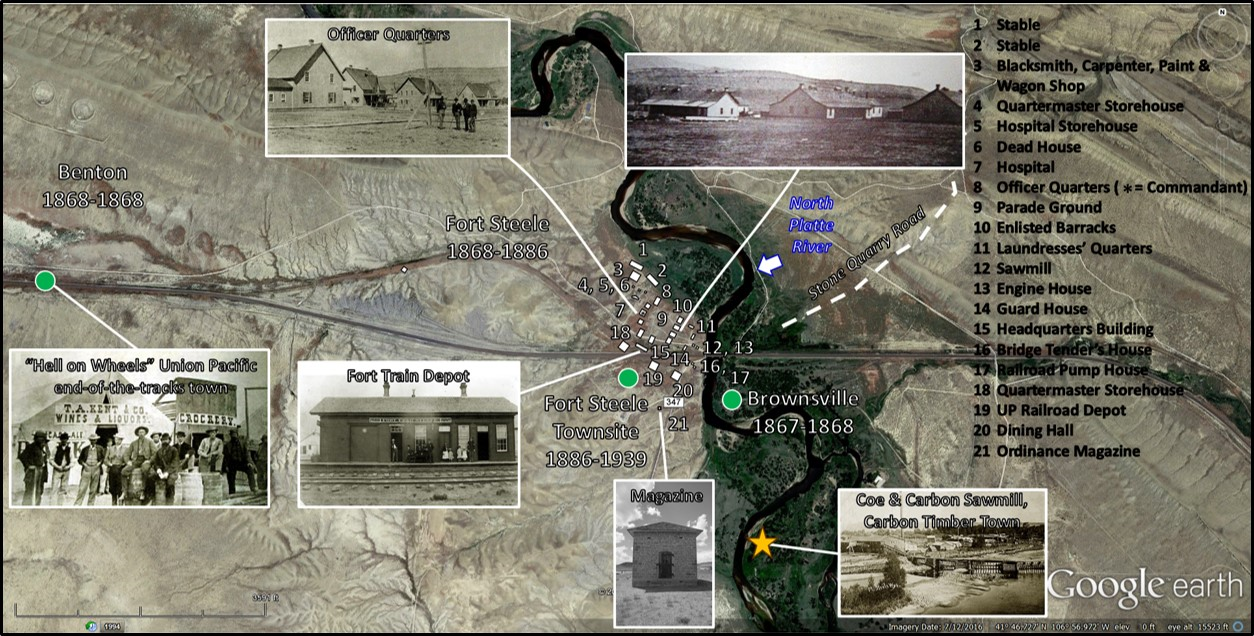

The community of Brownsville was established by speculators on the east side of the North Platte River in anticipation of the railroad in 1867. This land was squatting on railroad land. The commanding officer declared all land within a three mile radius of Fort Steele a military reservation that prohibited civilian occupation. The residents of Brownsville moved to the western border of the boundary and established one of the most notorious end-of-track-towns Benton. The community had 25 saloons, 5 dance halls with games of chance and prostitutes for entertainment. The settlement’s population of 3,000 would increase nocturnally with an assortment of cowboys, miners, U.P. construction crews, tie hacks, and soldiers who would spend their evenings with Benton’s regular collection of gamblers, prostitutes, swindlers and thieves. On weekends, the number of town inhabitants could swell by a couple thousand individuals. The town only lasted 3 months but reportedly managed to bury over 100 souls that died in gunfights. Many of the residents moved on to Rawlins as the railroad track advanced. Benton holds the honor of being Wyoming’s first ghost town and possibly the most notorious “Hell-on-Wheels” town. Zane Grey included a fictionalized description of the Big Tent Saloon (an establishment with numerous incarnations along the U.P. route) where his main character, Neale, visits Benton in Chapter 15 of his novel The U.P. Trail:

“Lights began to flash up along the streets of Benton, and presently Neale became aware of a low and mounting hum, like a first stir of angry bees.

The loud and challenging strains of a band drew Neale toward the center of the main street, where men were pouring into a big tent.

He halted outside and watched. This strident, businesslike, quick-step music and the sight of the men and women attracted thereby made Neale realize that Benton had arisen in a day and would die out in a night; its life would be swift, vile, and deadly.”

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4684/4684-h/4684-h.htm

“Lights began to flash up along the streets of Benton, and presently Neale became aware of a low and mounting hum, like a first stir of angry bees.

The loud and challenging strains of a band drew Neale toward the center of the main street, where men were pouring into a big tent.

He halted outside and watched. This strident, businesslike, quick-step music and the sight of the men and women attracted thereby made Neale realize that Benton had arisen in a day and would die out in a night; its life would be swift, vile, and deadly.”

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4684/4684-h/4684-h.htm

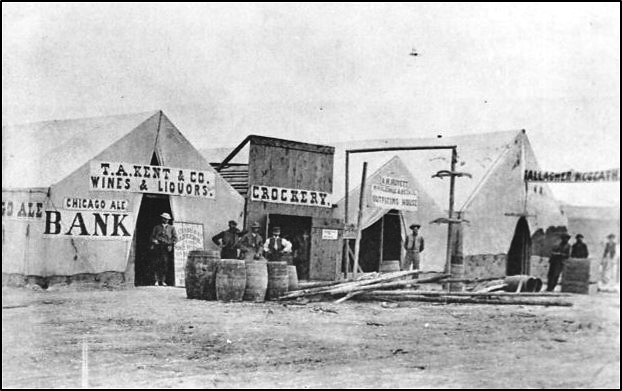

The Big Tent , Benton, Wyoming. The inhabitants of Benton stayed for only three months in 1868, before moving west to Rawlins.

Image: https://www.wyohistory.org/education/toolkit/railroad-and-wyoming.

Image: https://www.wyohistory.org/education/toolkit/railroad-and-wyoming.

Main Street, Benton, Wyoming Territory, 1868. Town was constructed with wood frames, false fronts and canvas, materials easy to assemble, strike, and reassemble at the next end-of-tracks-town.

Image: https://www.wyohistory.org/education/toolkit/railroad-and-wyoming.

Image: https://www.wyohistory.org/education/toolkit/railroad-and-wyoming.

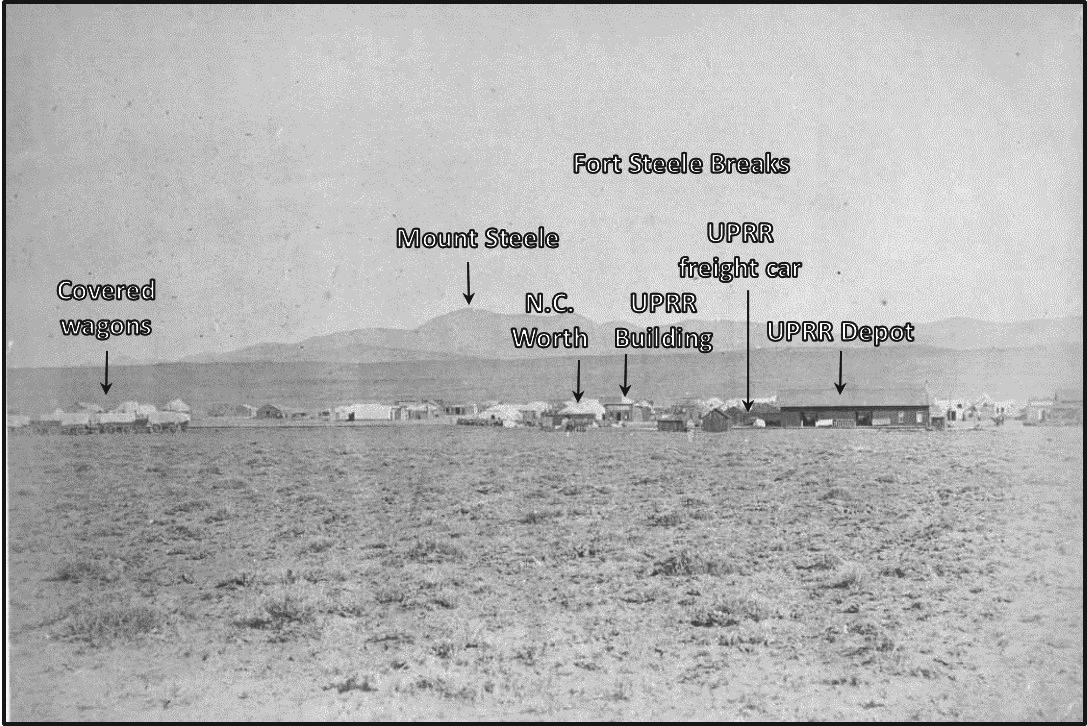

View north at log and frame buildings and canvas tents in Benton (Carbon County), Wyoming. The Fort Steele Breaks are in the distance with Mount Steele being the highest peak. Benton was erected on the sagebrush alkali flats just outside the 3-mile radius boundary of Fort Steele military reservation. The historical marker sign of image reads: “Benton, Wyoming Territory - the town that grew in a day and vanished in a night, but it was red hot while it lasted.”

Image: Hull, A.C., 1868, Benton, Wyoming Territory: Denver Public Library; http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll22/id/70447.

Image: Hull, A.C., 1868, Benton, Wyoming Territory: Denver Public Library; http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll22/id/70447.

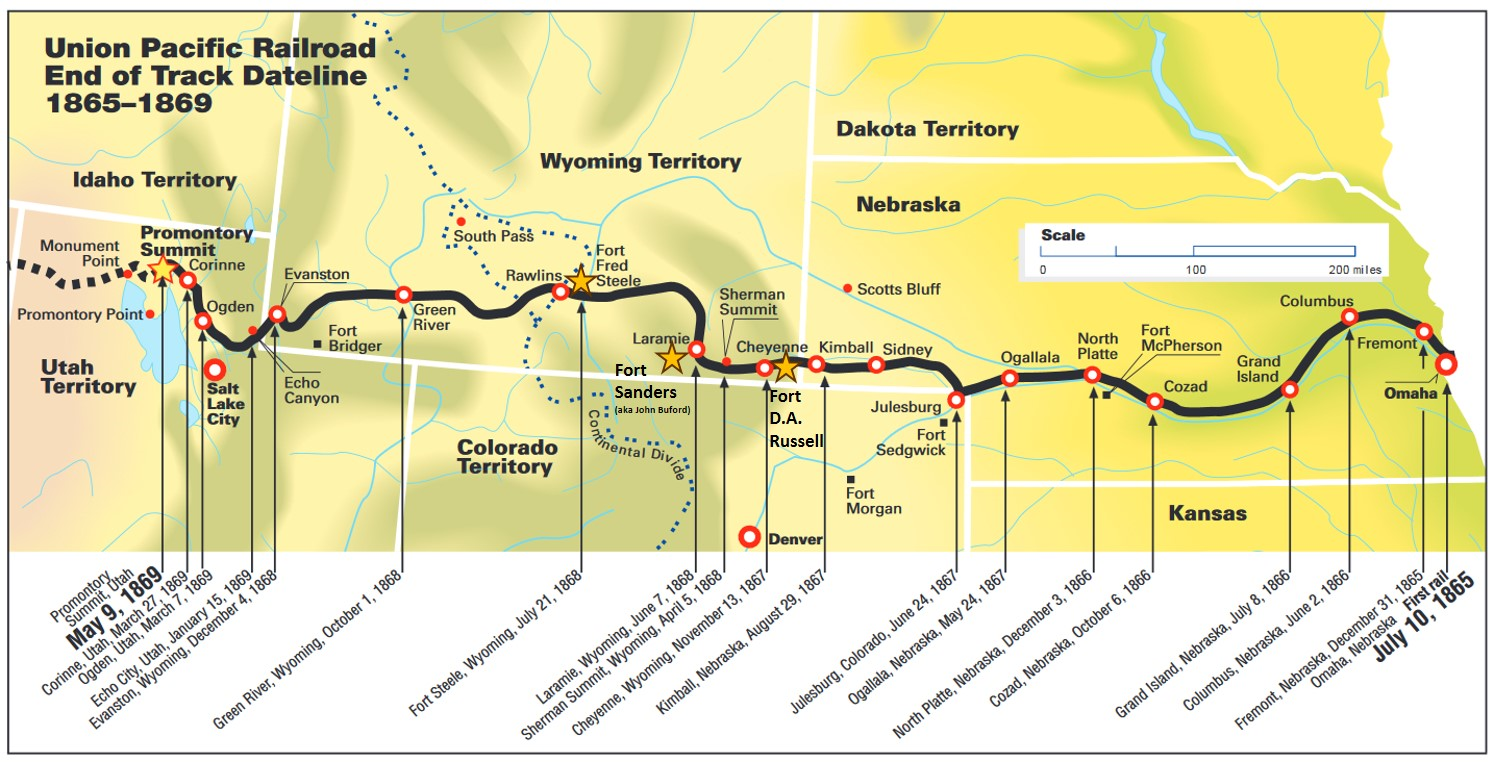

End-of-track timeline map, Omaha, Nebraska to Promontory Point, Utah. Stars mark location of forts established to protect the railroad and workers in Wyoming. Other smaller settlements are located between these towns.

Image: https://www.up.com/cs/groups/public/documents/up_pdf_nativedocs/pdf_eot_historical_up_maps.pdf.

Image: https://www.up.com/cs/groups/public/documents/up_pdf_nativedocs/pdf_eot_historical_up_maps.pdf.

Fort Fred Steele is 15 miles east of Rawlins where the Transcontinental railroad crossed the North Platte River. The post was established in 1868 to provide protection from Indians for railroad workers and trail emigrants. They also performed law enforcement duties in the region. The fort was named for Mexican and Civil War veteran Major General Frederick Steele. This was one of three railroad forts built by the Army in Wyoming. Fort D.A. Russell at Cheyenne and Fort Sanders (originally John Buford) at Laramie were the other two. A military supply depot was opened near the spring in Rawlins called Fort Rawlins in 1868. The closure date of the garrison is unknown but probably occurred at the same time Fort Steele was abandoned in 1886.

Fort Steele at North Platte River Union Pacific Railroad bridge crossing, Wyoming Territory. Number locations show building layout in 1881.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Fort Images: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/lincoln3.html.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Fort Images: http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/lincoln3.html.

Image: Cartoon by Ken Steele

West view of Fort Fred Steele, 1868 during construction. Troops lived in tents and only a few wooden structures had been erected. Ferdinand V. Hayden wrote his first field report of the 1868 Hayden Survey (first geologic investigation across Wyoming Territory) while camped here in early September.

Image: https://bypassedbyi80.com/county-pages-the-1915-lha-guidebook/carbon-county/.

Image: https://bypassedbyi80.com/county-pages-the-1915-lha-guidebook/carbon-county/.

East View of Fort Fred Steele, 1878. Troops now quartered in wooden structures. Fort is built on Upper Cretaceous Steele Shale. Hill in the background is composed of units of the Mesaverde Group.

Image: Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, Image #14024; http://spcrphotocollection.wyo.gov/luna/servlet/detail/SPCRACV~3~3~1053677~118249:FORTS--FORT-STEELE-#-1-OF-4?qvq=q:%3Dfort%20steele%20&mi=6&trs=172.

Image: Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, Image #14024; http://spcrphotocollection.wyo.gov/luna/servlet/detail/SPCRACV~3~3~1053677~118249:FORTS--FORT-STEELE-#-1-OF-4?qvq=q:%3Dfort%20steele%20&mi=6&trs=172.

Fort Steele geologic map, cross section AA’, and index.

Image: After Lynds, R.M., and Wrage, J.M., 2017, Preliminary geologic map of the Fort Steele quadrangle, Carbon County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 2017-5, 25 p., scale 1:24,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2017-ofr-05.pdf.

Image: After Lynds, R.M., and Wrage, J.M., 2017, Preliminary geologic map of the Fort Steele quadrangle, Carbon County, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 2017-5, 25 p., scale 1:24,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2017-ofr-05.pdf.

Fort Rawlins officer’s quarters, 1877.

Image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/%22Officers_quarters_at_Ft._Rawlins%2C_Wyoming%2C_May_7%2C_1877.%22_Two_men_and_a_woman_holding_a_baby_sit_in_front_of_the_crude_structure_-_NARA_-_531107.gif

Image: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/%22Officers_quarters_at_Ft._Rawlins%2C_Wyoming%2C_May_7%2C_1877.%22_Two_men_and_a_woman_holding_a_baby_sit_in_front_of_the_crude_structure_-_NARA_-_531107.gif

North view of the probable site of Fort Rawlins supply depot adjacent to Rawlins Spring.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Outcrop: Lee, W.T., Stone, R.W., Gale, H.S. and others, 1916 Guidebook of the western United States: Part B, Overland Route, with a side trip to Yellowstone Park: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 612, Plate XIII-A, after p. 60; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0612/report.pdf; Station: Hip Postcard, circa 1915, Rawlins Depot; https://www.hippostcard.com/listing/rawlins-wy-union-pacific-railroad-station-train-depot-rppc-postcard/369757;

Springs: Hull, D., 2013, Marker overlooking Rawlins Springs; https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=251800.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Outcrop: Lee, W.T., Stone, R.W., Gale, H.S. and others, 1916 Guidebook of the western United States: Part B, Overland Route, with a side trip to Yellowstone Park: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 612, Plate XIII-A, after p. 60; https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0612/report.pdf; Station: Hip Postcard, circa 1915, Rawlins Depot; https://www.hippostcard.com/listing/rawlins-wy-union-pacific-railroad-station-train-depot-rppc-postcard/369757;

Springs: Hull, D., 2013, Marker overlooking Rawlins Springs; https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=251800.

Construction of the Union Pacific gave rise to train towns every seven to ten miles along its route. These end-of track towns were temporary settlements for rowdy inhabitants and living quarters for workers (more than 7,000 towns west of the Missouri River were established by the Union Pacific). Brownsville and Benton were both short lived examples. Rawlins is a town that evolved from end-of-track to a division point for the railroad and a distribution site for commerce. The selection of Rawlins for the State Penitentiary in 1886 and the building of the Lincoln Highway in 1916 continued its development. The population, economy and culture of all southern Wyoming along the U.P. strip expanded faster than in the rest of the state. Many of the important public facilities are located here (Capitol, university, penitentiary, etc.). The geography of the Rawlins area is largely due to the tectonic transformation of the Laramide Orogeny (70-55 million years ago). Rawlins area has witnessed many western travelers and historic technological changes pass through the area at the foot of the Rawlins Uplift. Rawlins is also located along the path of many transcontinental routes across the continent that helped transformed the American continent.

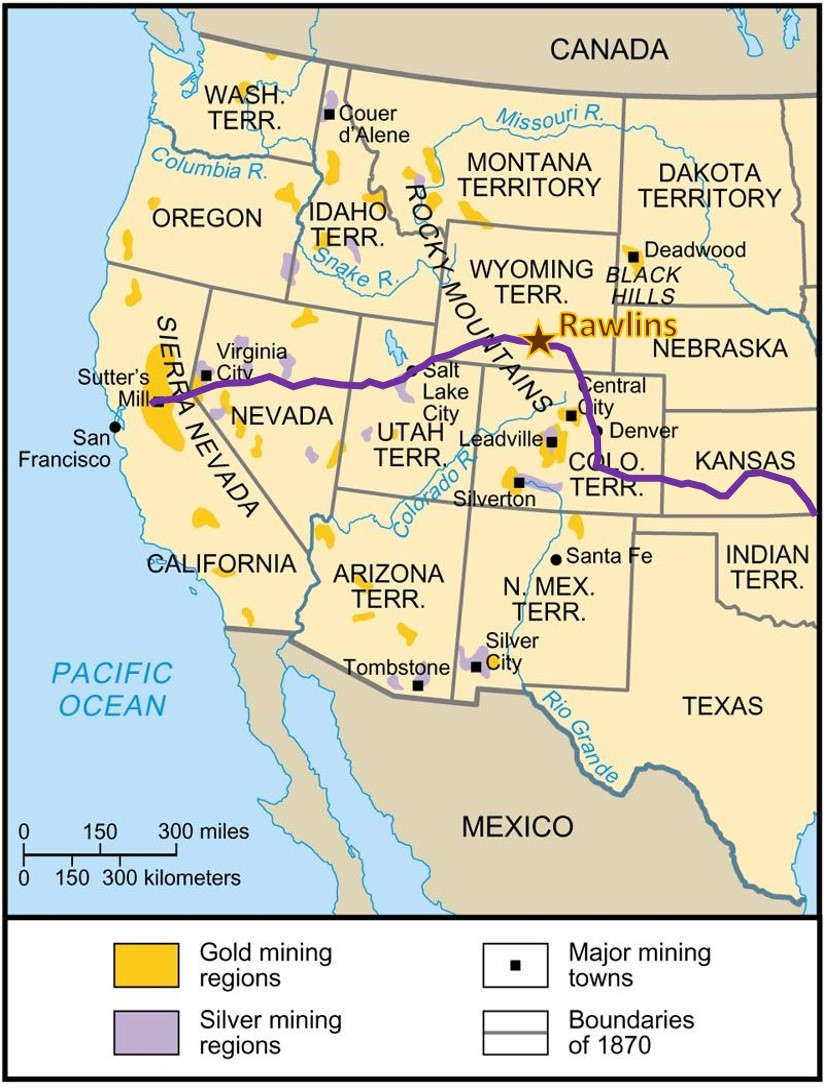

1849 Cherokee Trail/Overland Stage wagon road to the California gold field from Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The trail was used through the early 1890s.

Image: After https://www.pinterest.com/pin/316026098827735883/.

Image: After https://www.pinterest.com/pin/316026098827735883/.

The route and elevation profile of the Transcontinental Railroad. The Transcontinental telegraph of 1861 was realigned to follow the railroad in 1869.

Image: After Wells, C.H., 1867, Harpers Weekly; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Transcontinental_Railroad#/media/File%3APacific_Railroad_Profile_1867.jpg.

Image: After Wells, C.H., 1867, Harpers Weekly; https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Transcontinental_Railroad#/media/File%3APacific_Railroad_Profile_1867.jpg.

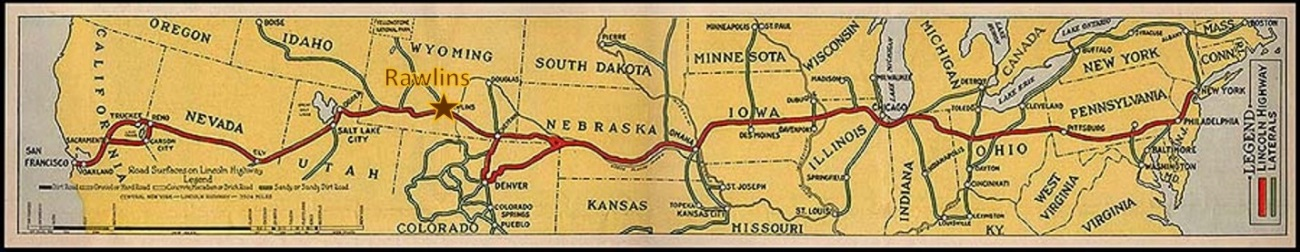

The Lincoln Highway route the first coast to coast roadway.

Image: After https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/LH-Map-75.jpg/800px-LH-Map-75.jpg

Image: After https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/LH-Map-75.jpg/800px-LH-Map-75.jpg

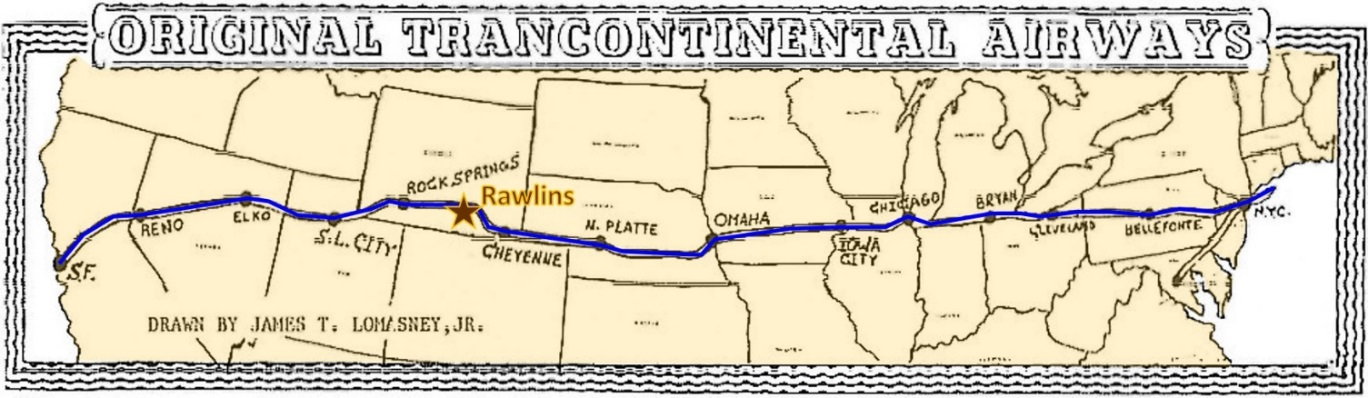

Route map of the first coast to coast airmail service, 1921

Image: After http://www.pathealy.com/flyingadventures/transcon10/index.html.

Image: After http://www.pathealy.com/flyingadventures/transcon10/index.html.

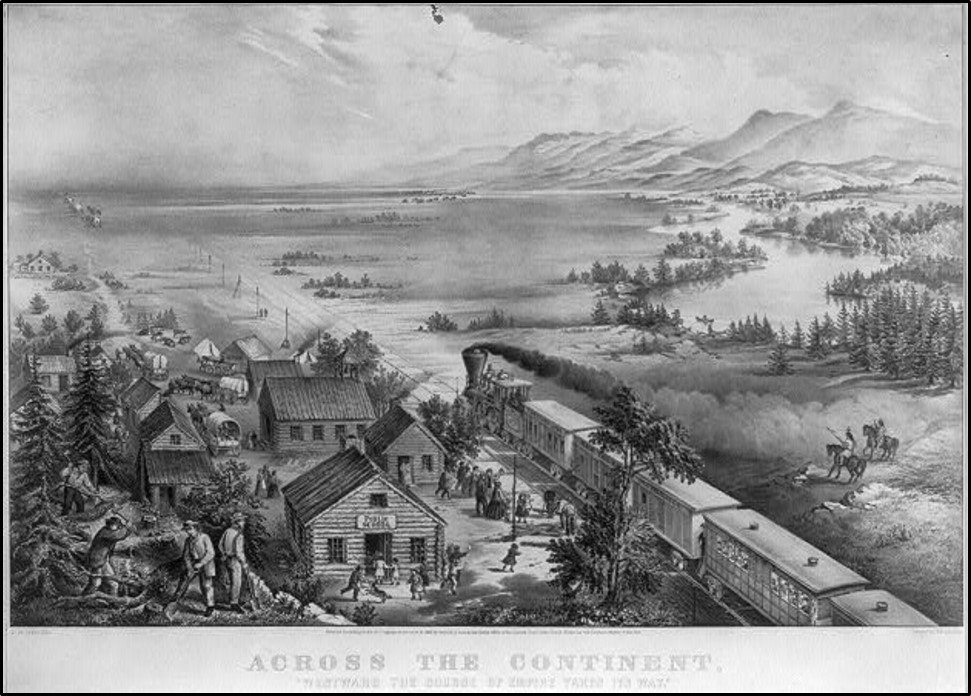

“Across the Continent, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” art by F. F. Palmer, published by Currier and Ives, New York, NY, 1868. The print captures the national spirit of “Manifest Destiny” that inspired those that crossed the Rawlins Uplift. The print shows a settlement of log buildings, with school and church, on the edge of the prairie; a steam railroad train is headed west with many passengers and covered wagons are departing for the west as well; Natives on horseback are visible on the right, with a river and mountains in the background on the upper right. The Rawlins Uplift lies ahead along the transcontinental way.

Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printhdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print.

Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA; http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printhdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print.

Rawlins Mesaverde Sandstone Quarries

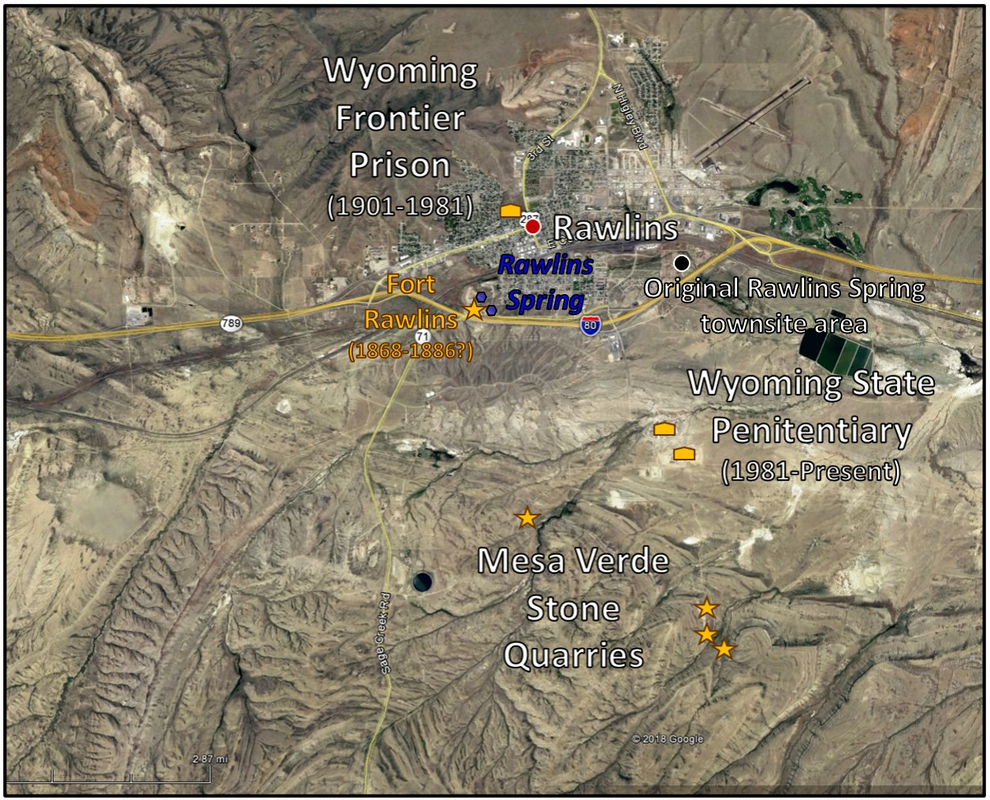

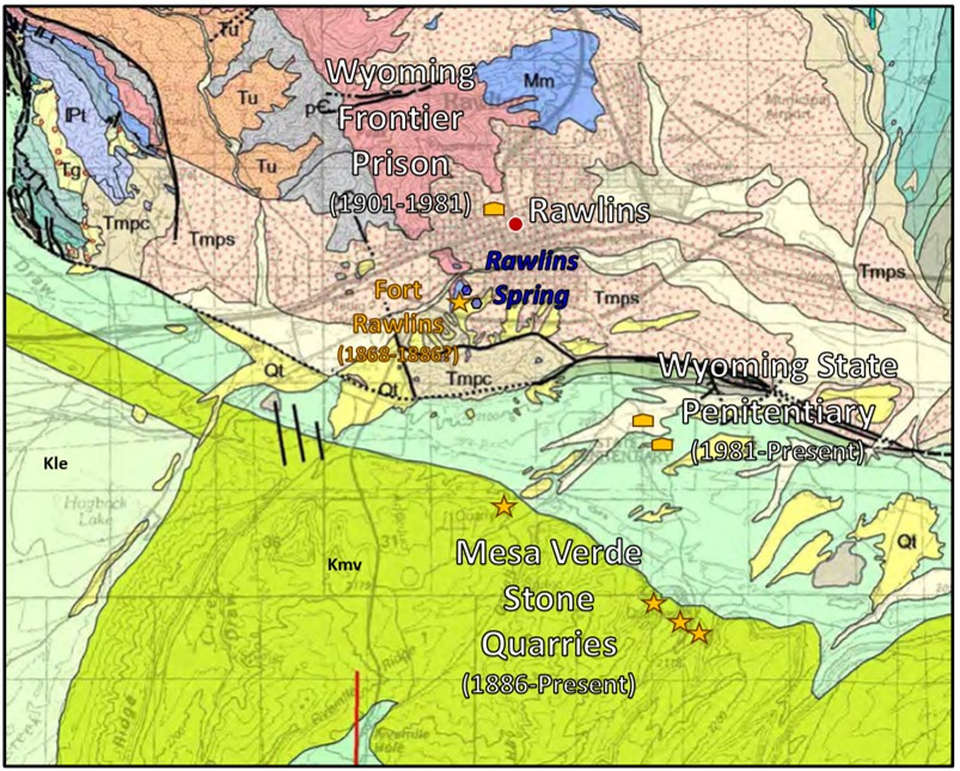

Wyoming’s Territorial Legislature approved Rawlins as the site for a penitentiary in 1886. The decision was influenced by the access to railroad transportation and the isolated location on the edge of the Red Desert that would make escape difficult. Construction delays and unfavorable economic conditions delayed completion until 1901, eleven years after statehood was gained. The structure, called “Old Pen,” remained open until 1981 when it was replaced by a new structure south of town. Stone for the “Old Pen” was quarried locally about five miles south of Rawlins near the new Penitentiary. The quarried Upper Cretaceous Mesaverde Group gray-white stone, called the “Rawlins Sandstone,” was also used on Merica Hall at the University of Wyoming and the Wyoming State Capitol buildings. The old penitentiary was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983 and was reopened as the Wyoming Frontier Prison museum in 1987.

Top: Aerial image of “Rawlins Sandstone” quarries, the penitentiaries, Rawlins Spring, Fort Rawlins, and the original townsite south of the railroad along Sugar Creek. Bottom: Geologic map of the same area showing quarries within the Mesaverde Group. Location of Frontier Prison, State Penitentiary, Fort Rawlins, and Rawlins Spring are shown. The non-alkaline water of the spring is rising from the Cambrian Flathead near the Mississippian Madison Limestone contact.

mage: Top: Google Earth; Bottom: : McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf

mage: Top: Google Earth; Bottom: : McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf

Left: Photo of the 19th Century Rawlins quarry with owner James McPherson in upper left corner who opened the mine in 1886. Right: recent photo of quarry. The quarry is at northwest ¼ Section 4, Township 20 North, Range 87 West (historic quarry); west ½ of Section 2, 3, 5, 9, northwest ¼ of 10 and 16, Township 20 North, Range 87 West, southwest ¼ of southwest ¼ Section 34, T21N R87W, Carbon County.

Image: Left: The Rawlins Republican, July 2, 1897; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/553d78dbe4b0786b41e0e2ca/t/58e9515746c3c45cf04cf04b/1491685726681/1897-0702-unmarked-Rawlins+Republican+%28Illustrated+Number%29+no.+32+July+02%2C+1897%2C+page+1-unmarked.pdf; Right: Wyoming Capitol Square Project, 2017; http://www.wyomingcapitolsquare.com/construction-updates-1/2017/4/8/sandstone-restoration-efforts-on-the-west-wing-of-the-capitol.

Image: Left: The Rawlins Republican, July 2, 1897; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/553d78dbe4b0786b41e0e2ca/t/58e9515746c3c45cf04cf04b/1491685726681/1897-0702-unmarked-Rawlins+Republican+%28Illustrated+Number%29+no.+32+July+02%2C+1897%2C+page+1-unmarked.pdf; Right: Wyoming Capitol Square Project, 2017; http://www.wyomingcapitolsquare.com/construction-updates-1/2017/4/8/sandstone-restoration-efforts-on-the-west-wing-of-the-capitol.

Primordial quarry species Flintstoneous bedrockius.

Image: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/604537949956937579/.

Image: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/604537949956937579/.

Rawlins quarry topographic map (top) and outcrop photo (bottom).

Image: Harris, R.E., 2003, Decorative stones of Southern Wyoming; Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular No. 42. Fig. 89 & 90, p. 36; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2003-pic-42.pdf.

Image: Harris, R.E., 2003, Decorative stones of Southern Wyoming; Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular No. 42. Fig. 89 & 90, p. 36; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2003-pic-42.pdf.

Wyoming Penitentiary, 1901-1981, Rawlins. The locally quarried Mesaverde Group grey-white sandstone was used in the construction of this “lockup on the range.”

Image: Top: https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/wyomings-first-state-prison; Bottom Left: After http://wyomingfrontierprison.org/; Bottom Right: https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/wyoming/this-penitentiary-in-wy-is-haunted/.

Image: Top: https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/wyomings-first-state-prison; Bottom Left: After http://wyomingfrontierprison.org/; Bottom Right: https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/wyoming/this-penitentiary-in-wy-is-haunted/.

Rawlins Iron Ore Quarries and Mines

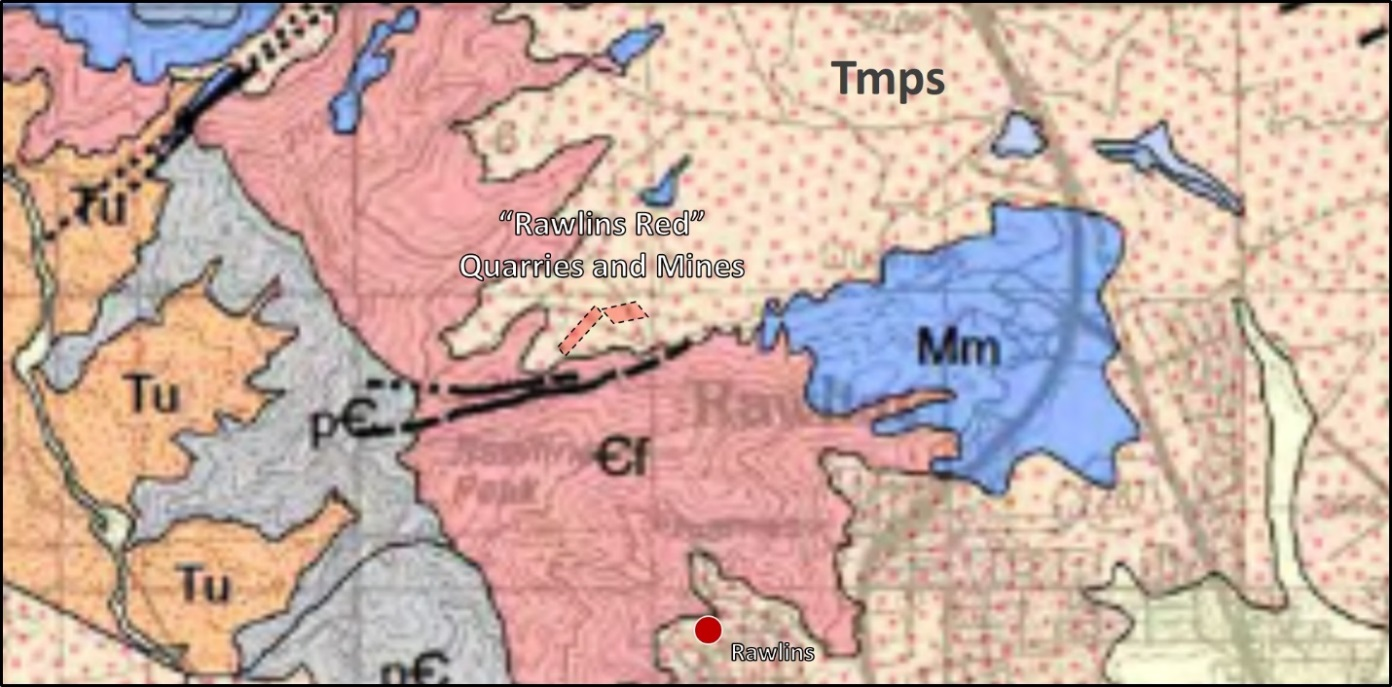

Iron oxide was mined one and a half miles north of Rawlins from 1870 to early 1900s. The ore was used as flux in copper smelting and pigment for paint. A paint mill was built to produce a pigment known as “Rawlins Red.” The paint had a durability that resisted mold and fungus on wood and rust on metal. Red paint became a popular color for railroad boxcars, barns, sheds, schoolhouses and metal structures due to its preservative properties. The first paint applied to the Brooklyn Bridge when completed in 1883 was Rawlins Red (approved in building plans, 1869).

The ore was quarried from surface pits and underground mines in the cornering quarter Sections 4, 5, 8 & 9, Township 21 North, Range 87 West; and in the adjacent northeast ¼ of southwest ¼, Section 31, Township 22 North, Range 87 West. These mines and quarries are on private land. The ore occurs in the upper most Flathead Formation near the contact with the overlying Madison Formation. The ore was deposited as glauconite, siderite and hematite in the Cambrian sea that flooded the Wyoming shelf. The ore concentrated in later stream channels in the upper part of the Flathead.

The ore was quarried from surface pits and underground mines in the cornering quarter Sections 4, 5, 8 & 9, Township 21 North, Range 87 West; and in the adjacent northeast ¼ of southwest ¼, Section 31, Township 22 North, Range 87 West. These mines and quarries are on private land. The ore occurs in the upper most Flathead Formation near the contact with the overlying Madison Formation. The ore was deposited as glauconite, siderite and hematite in the Cambrian sea that flooded the Wyoming shelf. The ore concentrated in later stream channels in the upper part of the Flathead.

Rawlins Red iron ore quarries and mines north of Rawlins. Geologic notation shown on index above.

Image: Top: Google Earth; Bottom: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

Image: Top: Google Earth; Bottom: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

Rawlins Red outcrop north of Rawlins. Hematite shows rusty red to dark, blackish blue ore.

Image: Sutherland, W.M., and Cola, E.C., 2015, Iron resources in Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations, Fig. 20, p. 58; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/iron-resources-in-wyoming-2015/.

Image: Sutherland, W.M., and Cola, E.C., 2015, Iron resources in Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations, Fig. 20, p. 58; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/iron-resources-in-wyoming-2015/.

The area was most likely use by Paleoindians for the pigment, but all evidence of their presence has been removed by subsequent mining of the ore. An estimated total of 150,000 tons of ore were produced for flux and pigment from the Rawlins Red hematite deposits (Wilson, 1976).

Cartoon by Ken Steele

The Brooklyn Bridge with “Rawlins Red” painted cables and iron girders on a Currier & Ives lithograph, 1877.

Image: Patell, C.R.K., 2012, Rawlins Red; https://www.pinterest.com/pin/857372847786135791/

Image: Patell, C.R.K., 2012, Rawlins Red; https://www.pinterest.com/pin/857372847786135791/

Geology of Rawlins Uplift

The Rawlins Uplift is about 50 miles long and 20 miles wide and trends North 25 West. It is a basement cored, asymmetrical arch with forelimb dips to the southwest of 30 to 90 degrees. The back limb dips gently into the Hanna Basin at 10 to 15 degrees east-northeast. The structure is bound on the northwest and west by the Bell Spring-Rawlins fault (Blackstone, 1991, Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations RI-47). The fault strike changes direction southeastward beginning in Township 23 North, Range 88 West. By Township 21 North, Range 86 West the fault is trending east-west and bounds the south flank of Grenville Dome.

Offset of the Precambrian surface on the bounding fault decreases from about 10,000 to 5,000 feet northward. Rawlins Peak is the highest point in the uplift at 7,804 foot elevation. This makes the differential relief of the Rawlins Uplift with the deepest part of the Great Divide Basin to the west 30,000 feet. The Hanna Basin has about 38,000 feet of differential relief to the east.

Offset of the Precambrian surface on the bounding fault decreases from about 10,000 to 5,000 feet northward. Rawlins Peak is the highest point in the uplift at 7,804 foot elevation. This makes the differential relief of the Rawlins Uplift with the deepest part of the Great Divide Basin to the west 30,000 feet. The Hanna Basin has about 38,000 feet of differential relief to the east.

Wyoming basement structure map. The maximum depth of Archean granitic rock feet in the Great Divide Basin is -20,000 and at -30,000 feet in the Hanna Basin. The Rawlins Uplift has a maximum elevation of about +7,800 feet resulting in differential relief of about 5.5 to 7 miles on the basement.

Image: After Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1993, Precambrian basement map of Wyoming—Outcrop and structural configuration: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Map Series 43, scale 1:1,000,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1993-ms-43.pdf.

Image: After Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1993, Precambrian basement map of Wyoming—Outcrop and structural configuration: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Map Series 43, scale 1:1,000,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1993-ms-43.pdf.

Geologic map of the Rawlins Uplift. Geologic notation shown on index above.

Image: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

Image: McLaughlin, J.F., and Fruhwirth, Jeff, 2008, Preliminary geologic map of the Rawlins 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Sweetwater counties, southeastern Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 08-4, scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2008-ofr-04.pdf.

Structural cross section SS’, Rawlins Uplift

Image: After Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1991, Tectonic relationships of the southeastern Wind River Range, southwestern Sweetwater Uplift and Rawlins Uplift, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Report of Investigations 47, Plate 2; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1991-ri-47.pdf.

Image: After Blackstone, D.L., Jr., 1991, Tectonic relationships of the southeastern Wind River Range, southwestern Sweetwater Uplift and Rawlins Uplift, Wyoming: Geological Survey of Wyoming [Wyoming State Geological Survey] Report of Investigations 47, Plate 2; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1991-ri-47.pdf.

Aerial Image of Rawlins area Laramide tectonic features.

Image: Google Earth

Image: Google Earth

The Laramide Orogeny broke up the Sevier foreland into the present mountains and basins of Wyoming. Archean age basement rocks were faulted along preexisting weakness zones in the crust into a fabric of anastomosing arches. The faulted blocks in the Rawlins area are all part of the southern accreted terranes of the Wyoming Province. This area consolidated as part of the craton about 2.63 billion years ago.

Major subdivisions of the Wyoming Craton area.

Image: Mueller, P., Mogk, D., Wooden, H.J., 2019, The Wyoming Province: A Unique Archean Craton: Power Point Presentation at EarthScope in the Northern Rockies Workshop; https://serc.carleton.edu/earthscoperockies/2019_wksp_program.html

Image: Mueller, P., Mogk, D., Wooden, H.J., 2019, The Wyoming Province: A Unique Archean Craton: Power Point Presentation at EarthScope in the Northern Rockies Workshop; https://serc.carleton.edu/earthscoperockies/2019_wksp_program.html

Generalized image of Rawlins area Laramide thrusting of basement blocks, Wyoming Craton. There is approximately 30,000 feet of differential elevation between the Rawlins Uplift and the center of the Great Divide Basin.

Image: Wroblewski, A.F.J.,2002, The Role of Hanna Basin in Revised Paleogeographic Reconstructions of the Western Interior Sea During the Cretaceous-Tertiary Transition:

Wyoming Geological Association Wyoming Basins Field Conference, Fig. 4, p. 21; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anton_Wroblewski/publication/300009738_The_Role_of_the_Hanna_Basin_in_Revised_Paleogeographic_Reconstructions_of_the_Western_Interior_Sea_During_the_Cretaceous-Tertiary_Transition/links/57080f6d08aea660813320d6/The-Role-of-the-Hanna-Basin-in-Revised-Paleogeographic-Reconstructions-of-the-Western-Interior-Sea-During-the-Cretaceous-Tertiary-Transition.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

Image: Wroblewski, A.F.J.,2002, The Role of Hanna Basin in Revised Paleogeographic Reconstructions of the Western Interior Sea During the Cretaceous-Tertiary Transition:

Wyoming Geological Association Wyoming Basins Field Conference, Fig. 4, p. 21; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anton_Wroblewski/publication/300009738_The_Role_of_the_Hanna_Basin_in_Revised_Paleogeographic_Reconstructions_of_the_Western_Interior_Sea_During_the_Cretaceous-Tertiary_Transition/links/57080f6d08aea660813320d6/The-Role-of-the-Hanna-Basin-in-Revised-Paleogeographic-Reconstructions-of-the-Western-Interior-Sea-During-the-Cretaceous-Tertiary-Transition.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

Generalized structural cross section across the Rawlins Uplift and Hanna Basin from seismic and well data. Abbreviations: C = Cambrian, P = Permian, T = Triassic, J = Jurassic, M = Muddy Shale, F = Frontier Formation, S = Steele Shale, MV = Mesaverde Group, L = Lewis Shale, MB = Medicine Bow Formation, F = Ferris Formation, H = Hanna Formation.

Image: After Wroblewski, A.F.J.,2002, The Role of Hanna Basin in Revised Paleogeographic Reconstructions of the Western Interior Sea During the Cretaceous-Tertiary Transition:

Wyoming Geological Association Wyoming Basins Field Conference, Fig. 5, p. 21; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anton_Wroblewski/publication/300009738_The_Role_of_the_Hanna_Basin_in_Revised_Paleogeographic_Reconstructions_of_the_Western_Interior_Sea_During_the_Cretaceous-Tertiary_Transition/links/57080f6d08aea660813320d6/The-Role-of-the-Hanna-Basin-in-Revised-Paleogeographic-Reconstructions-of-the-Western-Interior-Sea-During-the-Cretaceous-Tertiary-Transition.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

Image: After Wroblewski, A.F.J.,2002, The Role of Hanna Basin in Revised Paleogeographic Reconstructions of the Western Interior Sea During the Cretaceous-Tertiary Transition:

Wyoming Geological Association Wyoming Basins Field Conference, Fig. 5, p. 21; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anton_Wroblewski/publication/300009738_The_Role_of_the_Hanna_Basin_in_Revised_Paleogeographic_Reconstructions_of_the_Western_Interior_Sea_During_the_Cretaceous-Tertiary_Transition/links/57080f6d08aea660813320d6/The-Role-of-the-Hanna-Basin-in-Revised-Paleogeographic-Reconstructions-of-the-Western-Interior-Sea-During-the-Cretaceous-Tertiary-Transition.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

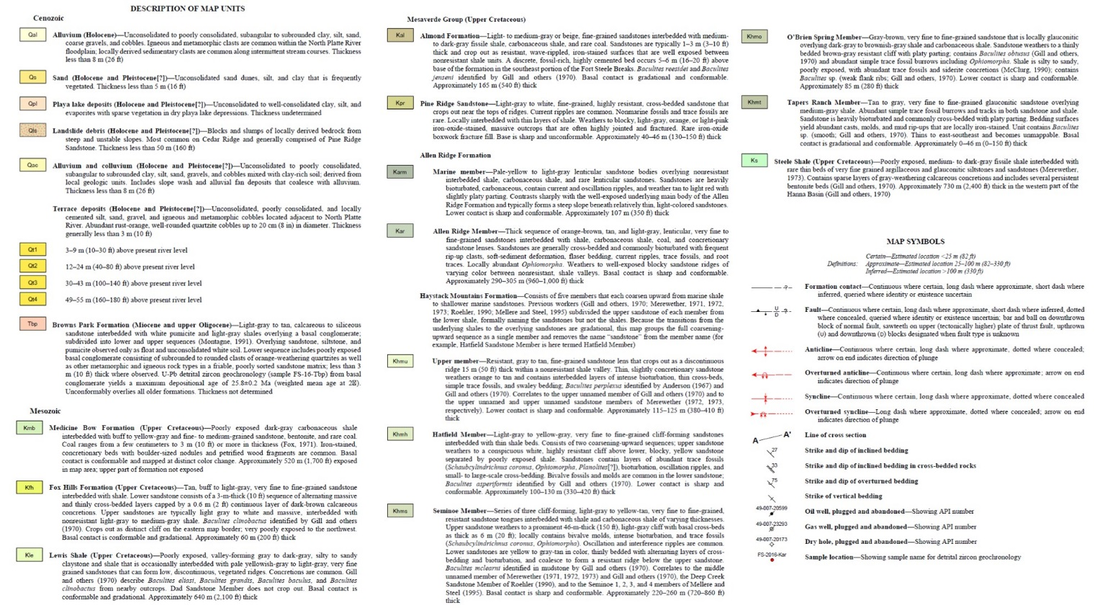

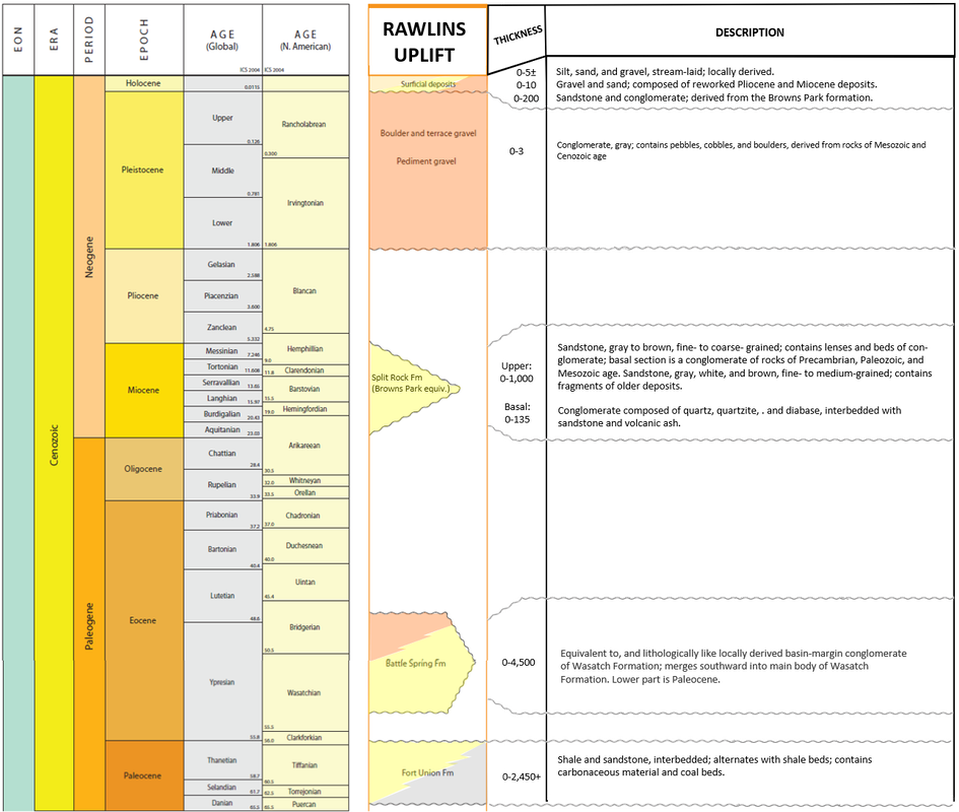

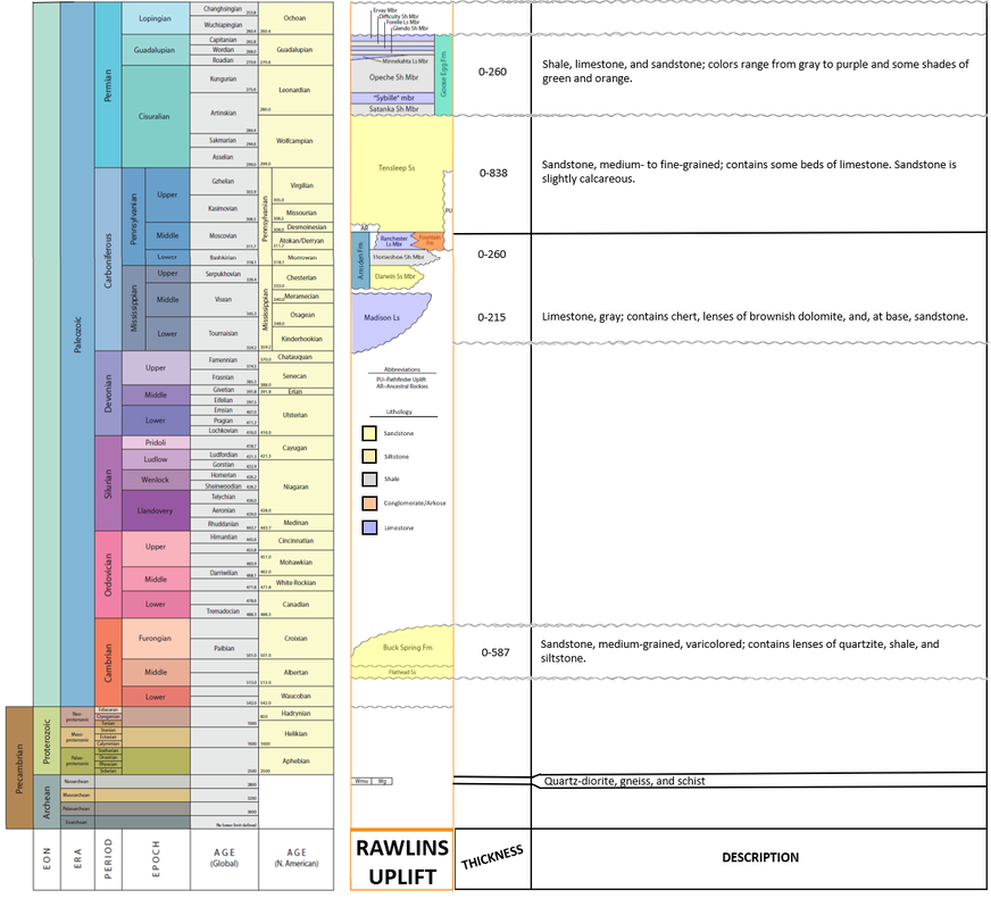

The oldest rock exposed in the core of the anticlinal arch is Archean basement. Undifferentiated Cambrian rocks of marine and fluvial origin overlie basement. Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian rocks are not present in the area of the uplift. Madison Limestone lies unconformably on the Cambrian units. It represents a time of shallow low latitude seas across Wyoming as the Appalachian orogeny occurred along eastern North America. The Pennsylvanian to Jurassic Sundance Formation were continued deposition on a passive margin shelf of Wyoming. The Sevier Orogeny began with the Jurassic Morrison Formation. This period was punctuated by flooding of the Western Interior seaway during the Cretaceous. The Uppermost Cretaceous Lance Formation marks the onsite of Laramide deformation and segmenting of the Sevier foreland. A brief description of units is given in the generalized rock column below.

Rawlins area generalized rock column. Gaps in the sedimentary record are colored white in Rawlins Uplift column and blank in the Description column.

Image: After George, L., Cardinal, D., and Winter, G, 2014, Stratigraphic Nomenclature Chart: Wyoming Geological Association DVD, Column 15; Berry, D. W., 1960, Geology and groundwater resources of the Rawlins area, Carbon County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1458, Table, p. 13-14; https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/1458/report.pdf.

Image: After George, L., Cardinal, D., and Winter, G, 2014, Stratigraphic Nomenclature Chart: Wyoming Geological Association DVD, Column 15; Berry, D. W., 1960, Geology and groundwater resources of the Rawlins area, Carbon County, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1458, Table, p. 13-14; https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/1458/report.pdf.

The material on this page is copyrighted