Wow Factor (3 out of 5 stars):

Geologist Factor (2 out of 5 stars):

Attraction

Historic base metal mining district in the Sierra Madre Mountains

History of Encampment and Sierra Madre Mountains

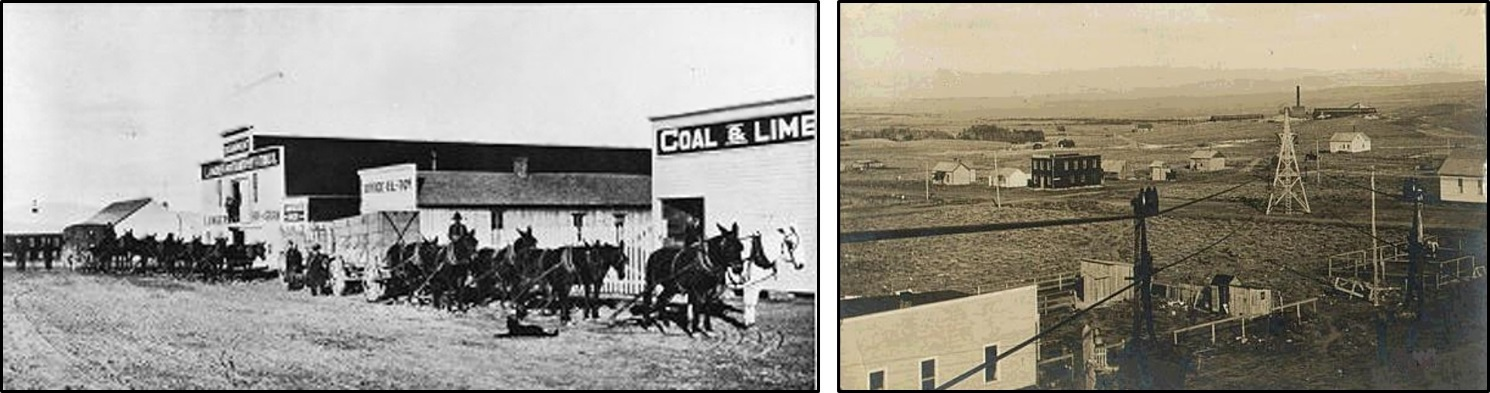

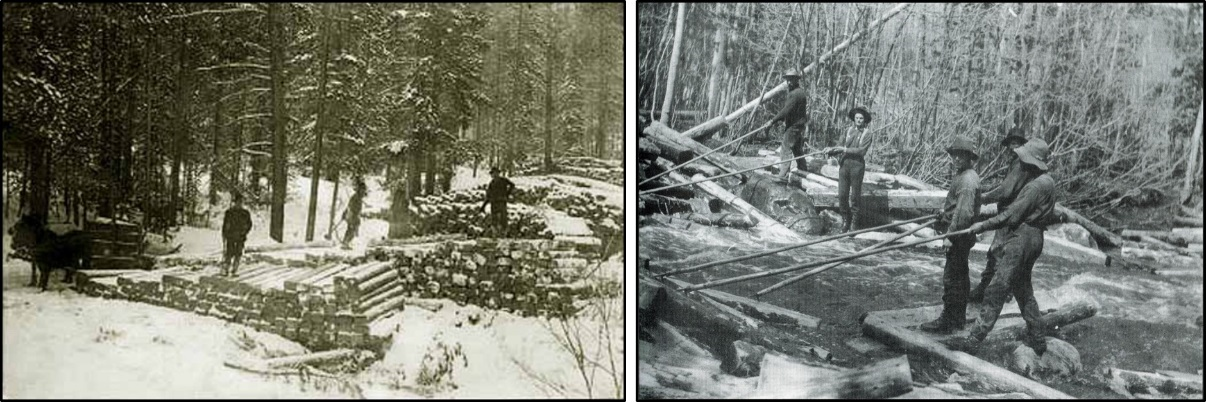

The Endurance river valley, along with the North Platte river valley, were used by the Ute Indians for hunting and fishing during the 1800s. Neighboring tribes probably also took advantage of the area’s bounty. The Sierra Madre and Medicine Bow Mountains region provided plentiful water and grassland for game and fish. Mountain men and traders first came to the area in the 1830s. Trappers held a rendezvous at a location they named “Camp le Grand” (aka Grand Encampment) at the north base of the mountains in 1838. A southern branch of the Cherokee trail from near Tie Siding to Fort Bridger was cut through the Sierra Madre in the 1840s. The route is near Wyoming Highway 70. The mountains also hosted a large amount of base metal and some precious metal ore deposits which brought miners and homesteaders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Encampment area boomed in the first decade of the twentieth century as a hub for copper mining.

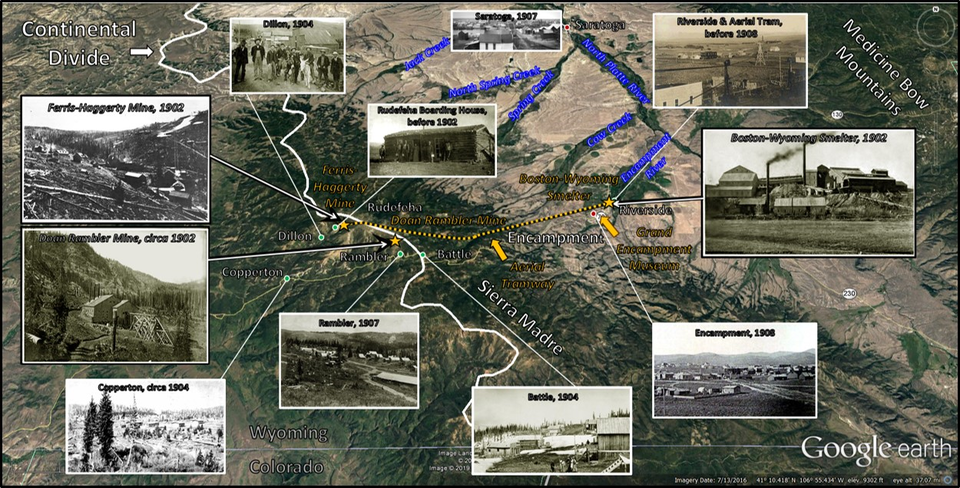

North aerial view of the Encampment area showing location of towns (red: current; green: abandoned), two major mines, and copper smelter (gold stars), aerial tramway and museum (gold arrows). Continental Divide shown by thick white line.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Photos: After Dobson, G.B., 2011, Wyoming Tales and Trails; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3.html.

Image: Base: Google Earth; Photos: After Dobson, G.B., 2011, Wyoming Tales and Trails; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3.html.

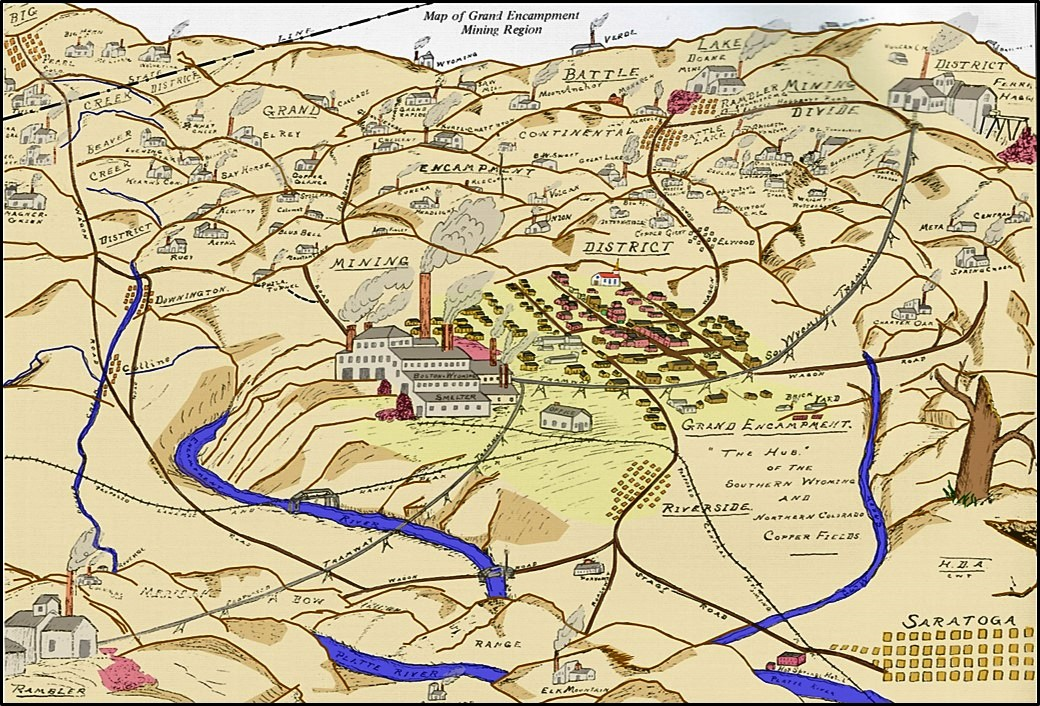

Encampment Mining District sketch map on application for National Register of Historical Places. View is to the southwest from Saratoga and shows the district and general area including the Boston-Wyoming Smelter, Southern Wyoming Tramway, Ferris-Haggerty (Rudefeha) Mine, Elwood, Battle Lake, Rambler, and Riverside (Doggett).

Image: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Frontispiece.

Image: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Frontispiece.

Left: Ore wagons with teams, circa 1905. Right: Aerial tramway through northern Encampment prior to 1908. Boston Wyoming Smelter is in the distance at smokestack, Riverside. The 16-mile tram consisted of 370 towers, 3 cable stations and 840 buckets that could hold as much as 700 pounds of ore each. The system transported ore, and miners, at 4-miles per hour by wood-fired steam power.

Image: Dobson, G.B., No Date, Grand Encampment: Wyoming Tales and Trails website; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3encamp2.html and http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3.html.

Image: Dobson, G.B., No Date, Grand Encampment: Wyoming Tales and Trails website; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3encamp2.html and http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3.html.

Original inhabitants of the land that would become Wyoming. Location of Encampment (red star), Tie Siding (small green dot), Army Posts (large yellow dots), and the future towns of Casper, Laramie and Rawlins (red-dashed white dots) is shown. The route of a southern branch of the Cherokee Trail is also displayed (red dashed line).

Image After https://www.mapsales.com/outlook-maps/state-wall-maps/wyoming-satellite-wall-map.aspx.

Image After https://www.mapsales.com/outlook-maps/state-wall-maps/wyoming-satellite-wall-map.aspx.

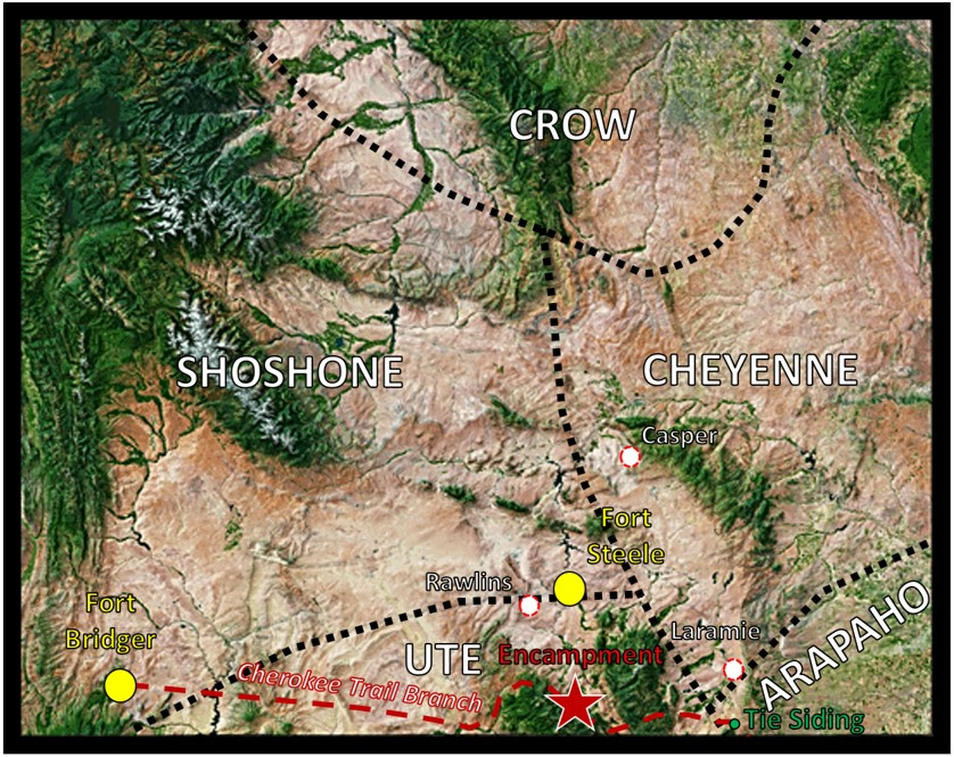

Tie hacks were the first to take residence in the area in the 1860s and 1870s. They cut and shaped ties for the Union Pacific Railroad and logs for Fort Steele (established 1868) during the winter. With the spring thaw, they floated the ties down creeks feeding the Endurance River to the North Platte River. They were followed by ranchers in the late 1880s. George Doane discovered copper in the Sierra Madre Mountains one-half mile north of Battle Lake in 1874. Copper float was traced to the Cascade Quartzite, Deep Lake Group along the north bank of Battle Creek. The Doane Rambler Mine was established a few years later. Ed Haggerty discovered a rich copper vein in the Mongolia Quartzite, Deep Lake Group in 1897. The Ferris-Haggerty Mine (originally known as the Rudefeha Mine after the first two letters of the partners last names: J. M. Rumsey, Robert Deal, George Ferris, and Ed Haggarty) was the most productive in the Encampment Mineral District. The first shaft was drilled in 1898. Ore production in 1899 was 250 tons shipped by wagon and nine teams of four horses to the smelter in Rawlins. George Emerson, a shady promoter, plotted the town of Grand Encampment in 1897 after the Rudefeha mine proved commercial. The U.S. Postal Service required that the “Grand” be dropped from the name when a post office was established.

The Rudefeha mine was renamed the Ferris-Haggerty mine after sale to George Emerson’s North American Copper Company in 1902. Haggerty had sold his interest to Ferris in 1899. Ferris died in a buggy accident in 1900. Emerson was instrumental in promoting a sixteen-mile aerial tram over the Continental Divide connecting the mine to the Boston-Wyoming Smelter in 1902 at Riverside, 1.5 miles northeast of Encampment. The tram was able to haul 350 tons of ore per day. Transportation costs decreased from $14.00 per ton to 7 cents per ton. The mine was resold again in 1904 to the Penn-Wyoming Copper Company after Emerson’s company financially collapsed due to frauds and over inflated asset values. A newspaper obituary on Emerson in 1918 summarized his management of the Ferris-Haggerty as “one of the largest mining swindles of the age.”

The town of Dillion was established one mile from the mine when the company town of Rudefeha prohibited alcohol. Bar owners relocated their business a mile downhill from Rudefeha in the new, alcohol-friendly site. This neighbor town hosted several taverns to refresh the citizens of Rudefeha. The communities of Copperton, Battle, Rambler, and Riverside were all established to support mineral interests in the Encampment Mining District. The Encampment Mining District had over 2,500 mineral interests and mines throughout the Sierra Madre during the copper boom.

After the Penn-Wyoming took over operations the Wyoming State Geologist optimistically reported “This new smelter and railroad have made the future of the Encampment district a certainty, as there has never been a doubt as to the ores here, and new work is going on all over the district’ (Beeler, H.C., 1907, Progress in the Wyoming Mines). The Saratoga and Encampment Valley Railroad construction that began in 1905 reached Encampment in 1908 to late to support mining. The Ferris-Haggerty mine and the smelter closed in 1908. The Doane Rambler mine remained active until 1912. The tram was taken down between 1910 and 1911. The Post Office closed in 1910. The short-lived copper boom in the Encampment Mining District was mostly over by 1909. The reasons for failure were the mining company’s mismanagement, overextended capitalization, fraudulent stock sales, a decrease in copper price and two destructive fires (1906 and 1907) at the under insured smelter. The laid-off miners moved away and most of the small communities were abandoned.

The total volume of copper produced from the district is not known but it is estimated that between 1899 and 1908 the region produced about 20-24 million tons of copper with some zinc, lead, silver, and gold.

The Rudefeha mine was renamed the Ferris-Haggerty mine after sale to George Emerson’s North American Copper Company in 1902. Haggerty had sold his interest to Ferris in 1899. Ferris died in a buggy accident in 1900. Emerson was instrumental in promoting a sixteen-mile aerial tram over the Continental Divide connecting the mine to the Boston-Wyoming Smelter in 1902 at Riverside, 1.5 miles northeast of Encampment. The tram was able to haul 350 tons of ore per day. Transportation costs decreased from $14.00 per ton to 7 cents per ton. The mine was resold again in 1904 to the Penn-Wyoming Copper Company after Emerson’s company financially collapsed due to frauds and over inflated asset values. A newspaper obituary on Emerson in 1918 summarized his management of the Ferris-Haggerty as “one of the largest mining swindles of the age.”

The town of Dillion was established one mile from the mine when the company town of Rudefeha prohibited alcohol. Bar owners relocated their business a mile downhill from Rudefeha in the new, alcohol-friendly site. This neighbor town hosted several taverns to refresh the citizens of Rudefeha. The communities of Copperton, Battle, Rambler, and Riverside were all established to support mineral interests in the Encampment Mining District. The Encampment Mining District had over 2,500 mineral interests and mines throughout the Sierra Madre during the copper boom.

After the Penn-Wyoming took over operations the Wyoming State Geologist optimistically reported “This new smelter and railroad have made the future of the Encampment district a certainty, as there has never been a doubt as to the ores here, and new work is going on all over the district’ (Beeler, H.C., 1907, Progress in the Wyoming Mines). The Saratoga and Encampment Valley Railroad construction that began in 1905 reached Encampment in 1908 to late to support mining. The Ferris-Haggerty mine and the smelter closed in 1908. The Doane Rambler mine remained active until 1912. The tram was taken down between 1910 and 1911. The Post Office closed in 1910. The short-lived copper boom in the Encampment Mining District was mostly over by 1909. The reasons for failure were the mining company’s mismanagement, overextended capitalization, fraudulent stock sales, a decrease in copper price and two destructive fires (1906 and 1907) at the under insured smelter. The laid-off miners moved away and most of the small communities were abandoned.

The total volume of copper produced from the district is not known but it is estimated that between 1899 and 1908 the region produced about 20-24 million tons of copper with some zinc, lead, silver, and gold.

Left: Stacking ties for winter storage near Encampment, 1912. Right: Spring tie drive as swollen waterways thaw.

Image: Left: Dobson, G.B., 2011,Grand Encampment: Wyoming Tales and Trails; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3encamp4.html;

Right: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Fig. on p. 65.

Image: Left: Dobson, G.B., 2011,Grand Encampment: Wyoming Tales and Trails; http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/ghost3encamp4.html;

Right: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Fig. on p. 65.

Saratoga & Encampment Railway Station, Encampment, Wyoming. The line was called the “Slow and Easy” arrived too late for the mining industry but was used extensively by the livestock industry. The line remained open until 1974.

Image: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Fig. on p. 58.

Image: After Moulten, C. and Del Bene, T.A., 2012, Grand Encampment: Images of America, Fig. on p. 58.

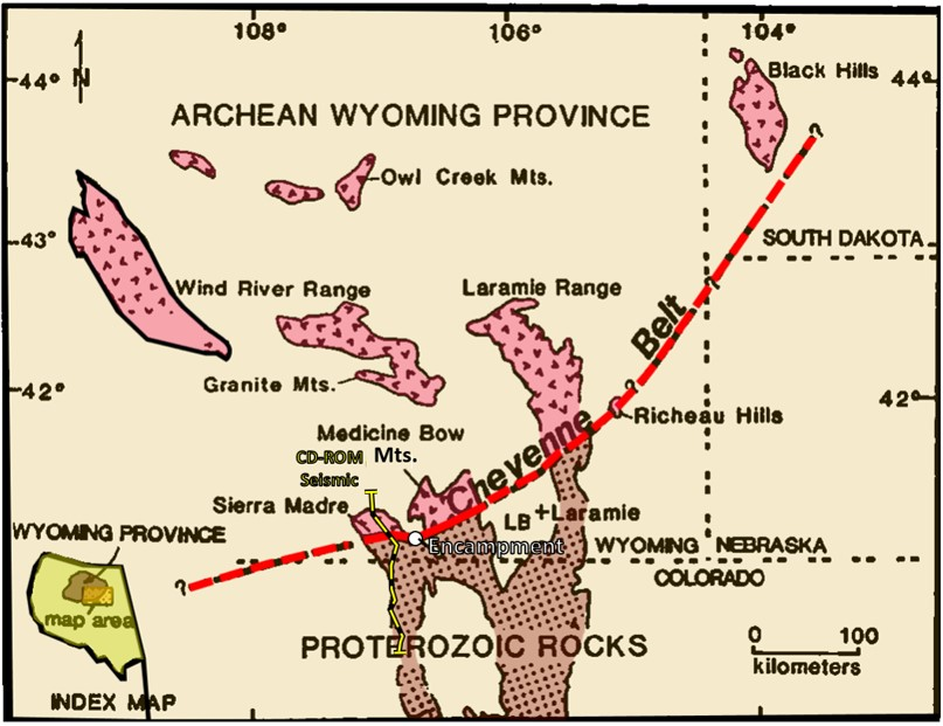

Geology of Encampment and Sierra Madre Mountains

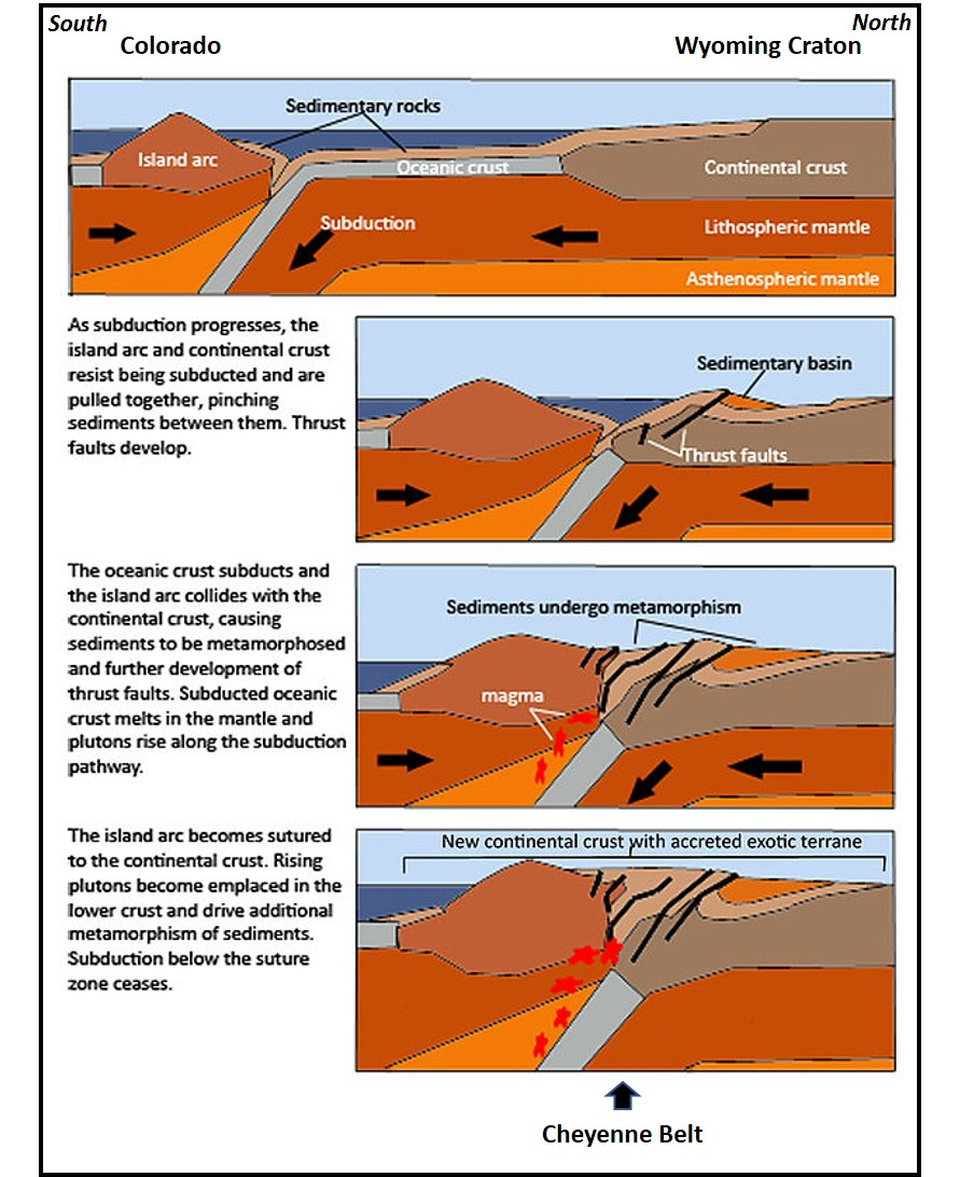

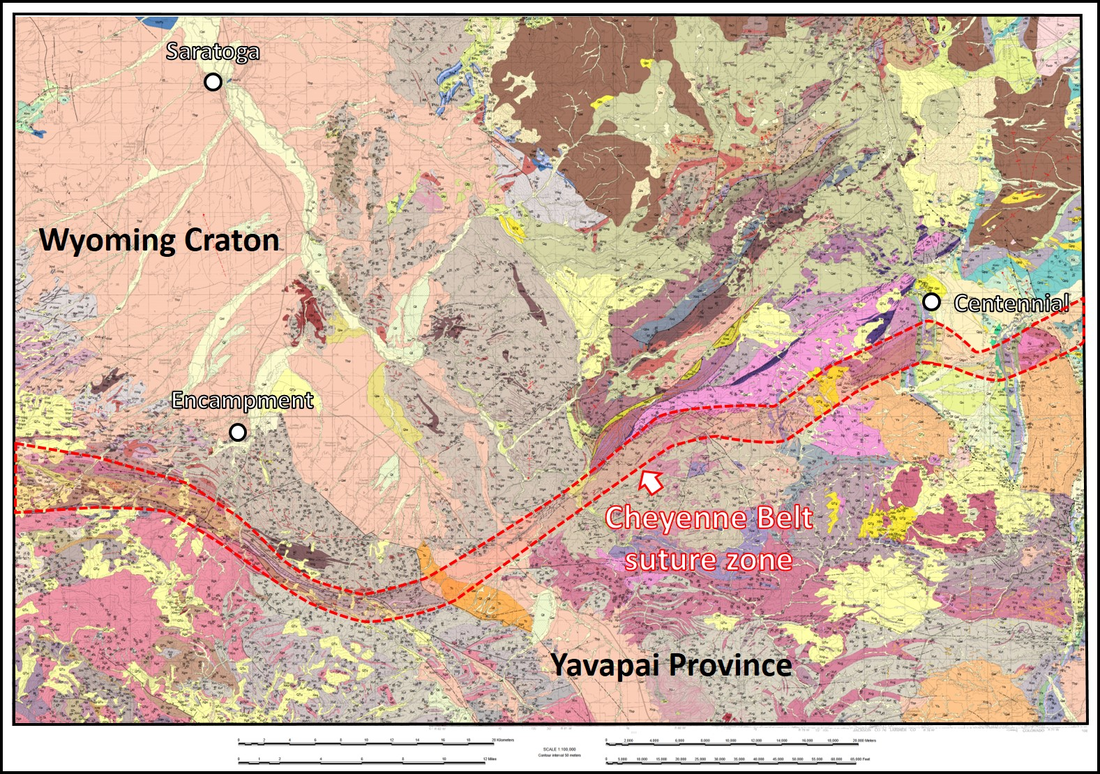

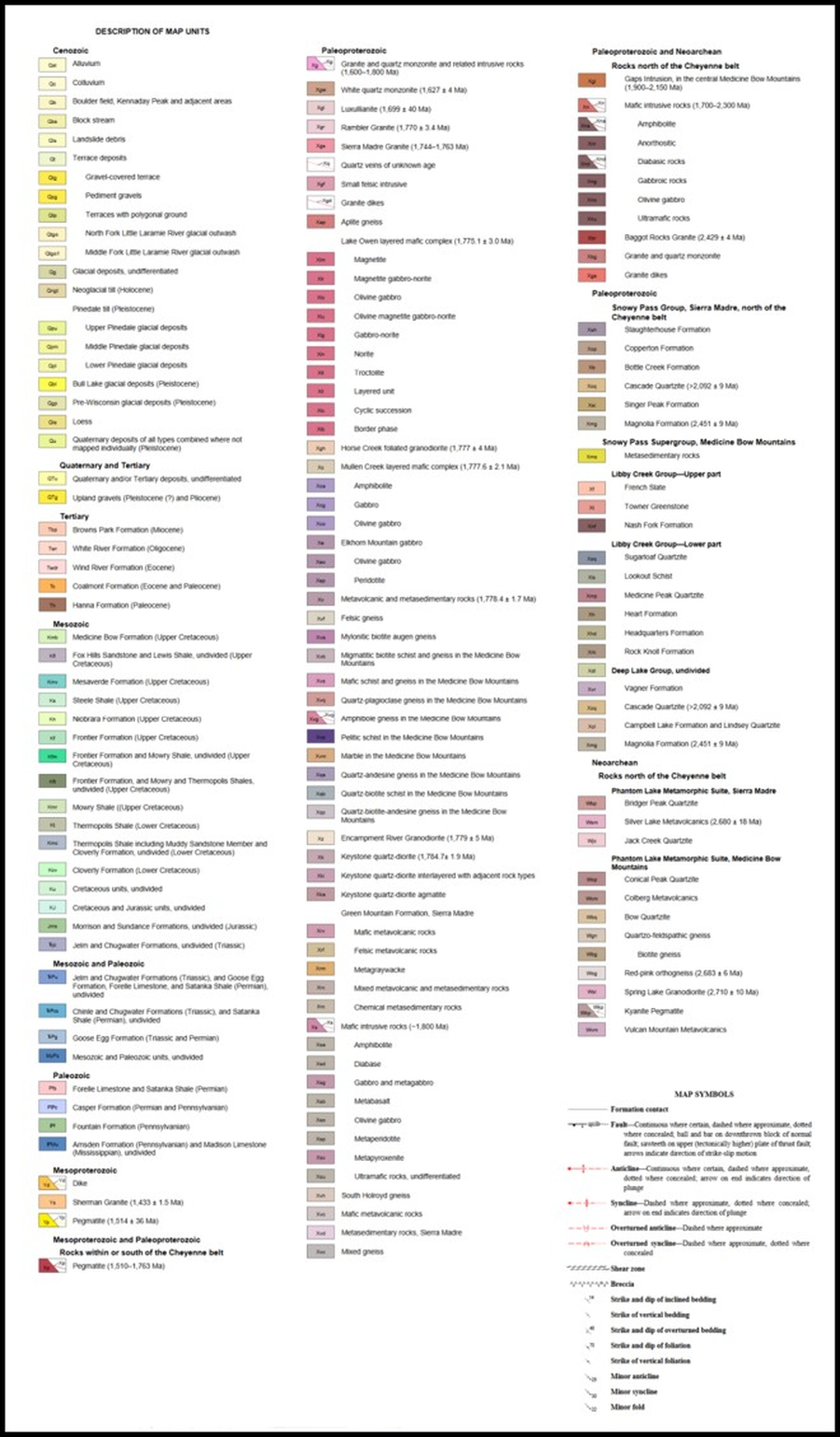

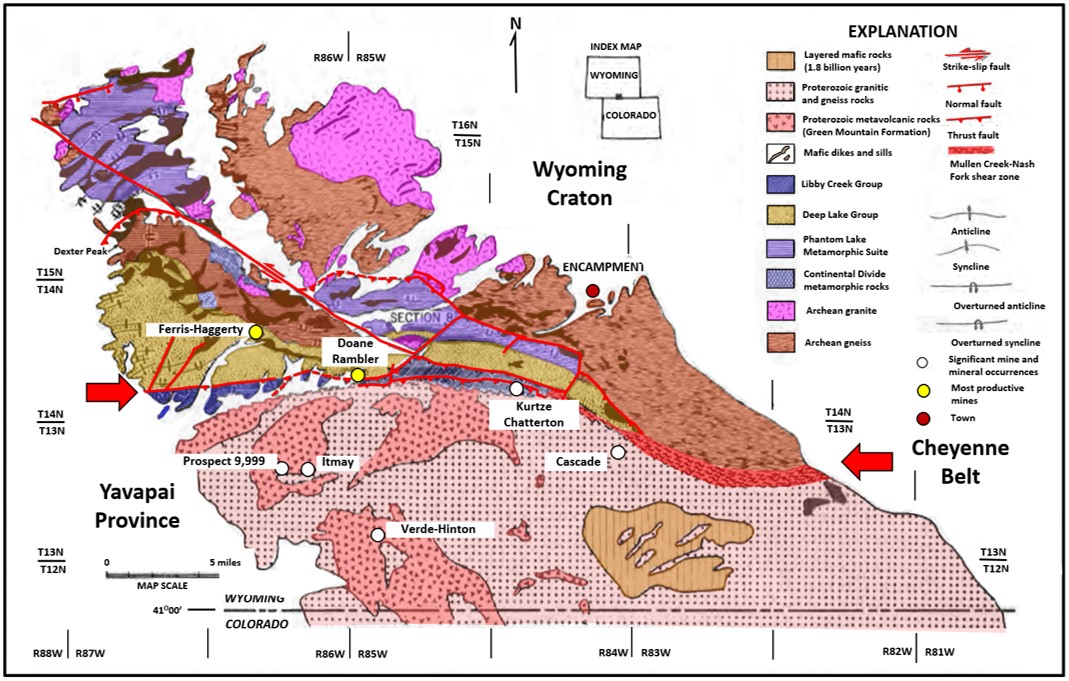

The Encampment Mining District is located along the tectonic suture zone between the Wyoming Craton and the Yavapai Province. An island arc chain to the south was thrust onto the Archean basement of the Wyoming Province in a 1.73-1.64 billion years ago collision. The suture zone is known as the Cheyenne Belt which includes the Mullen Creek-Nash Fork Shear Zone. Archean (> 2.5 billion years) crystalline rocks are unconformably overlain by about eight mile thick package of Proterozoic metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks north of the Cheyenne Belt. South of the suture are 12,000 feet of volcanogenic schists and gneisses of the Green Mountain Formation.

Location of Encampment along the Cheyenne Belt, Sierra Madre Mountains. Seismic line location shown by yellow and black dashed line.

Image: After Houston, R.S., Duebendorfer, E.M., Karlstrom, K.E., and Premo, W.R., 1989, A review of the geology and structure of the Cheyenne belt and Proterozoic rocks of southern Wyoming, in Grambling, J. A., and Tewksbury, B. J., Proterozoic geology of the southern Rocky Mountains: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society America Special Paper 235, Fig. 1, p. 2; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1cb7/e84df000e1a1431c312c2367f8d932e1dc79.pdf.

Image: After Houston, R.S., Duebendorfer, E.M., Karlstrom, K.E., and Premo, W.R., 1989, A review of the geology and structure of the Cheyenne belt and Proterozoic rocks of southern Wyoming, in Grambling, J. A., and Tewksbury, B. J., Proterozoic geology of the southern Rocky Mountains: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society America Special Paper 235, Fig. 1, p. 2; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1cb7/e84df000e1a1431c312c2367f8d932e1dc79.pdf.

Geologic cross section with data from CD-ROM Cheyenne belt seismic line (location shown on map above). Seismic reflection interpretation (red dots) based on migration picks. Orange areas—positive impedance contrast (impedance = product of density and seismic velocity); blue areas—negative impedance contrast. Dashed blue line—high-velocity body imaged by P- and S-wave tomography. A—Archean lithosphere, P—Proterozoic lithosphere, Pgm—Proterozoic Green Mountain block, Prb—Proterozoic Rawah block, FM—Farwell Mountain, LM—Lester Mountain, SC-FC—Soda Creek–Fish Creek shear zone. The border between Colorado and Wyoming is 41 degrees north latitude.

Image: After Tyson, A.R., Morozova, E.A., Karlstrom, K.E., Chamberlain, K.R., Smithson, S.B., Dueker, K.G., Foster, C.T., 2002, Proterozoic Farwell Mountain–Lester Mountain suture zone, northern Colorado: Subduction flip and progressive assembly of arcs: Geology, 30 (10), Fig. 2, p. 944; https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article/30/10/943/192307/?searchresult=1.

Image: After Tyson, A.R., Morozova, E.A., Karlstrom, K.E., Chamberlain, K.R., Smithson, S.B., Dueker, K.G., Foster, C.T., 2002, Proterozoic Farwell Mountain–Lester Mountain suture zone, northern Colorado: Subduction flip and progressive assembly of arcs: Geology, 30 (10), Fig. 2, p. 944; https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article/30/10/943/192307/?searchresult=1.

Collision and accretion of Colorado Island Arc along the Cheyenne Belt.

Image: After Wyoming Craton

Image: After Wyoming Craton

Geologic map and Index of greater Encampment area.

Image: After Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2004, Preliminary geologic map of the Saratoga 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Albany counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 04-10, version 1.1, 36 p., 1 pl., scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2004-ofr-10.pdf.

Image: After Sutherland, W.M., and Hausel, W.D., 2004, Preliminary geologic map of the Saratoga 30' x 60' quadrangle, Carbon and Albany counties, Wyoming: Wyoming State Geological Survey Open File Report 04-10, version 1.1, 36 p., 1 pl., scale 1:100,000; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-2004-ofr-10.pdf.

Close-up geologic map of Precambrian rocks, Sierra Madre Mountains, Wyoming. The Archean Wyoming Craton is to the north and the Yavapai Province lies to the south. The Cheyenne Belt suture lies between (red arrows).

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado; Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig. 1, p. 2; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1986-ri-37.pdf.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado; Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig. 1, p. 2; https://www.wsgs.wyo.gov/products/wsgs-1986-ri-37.pdf.

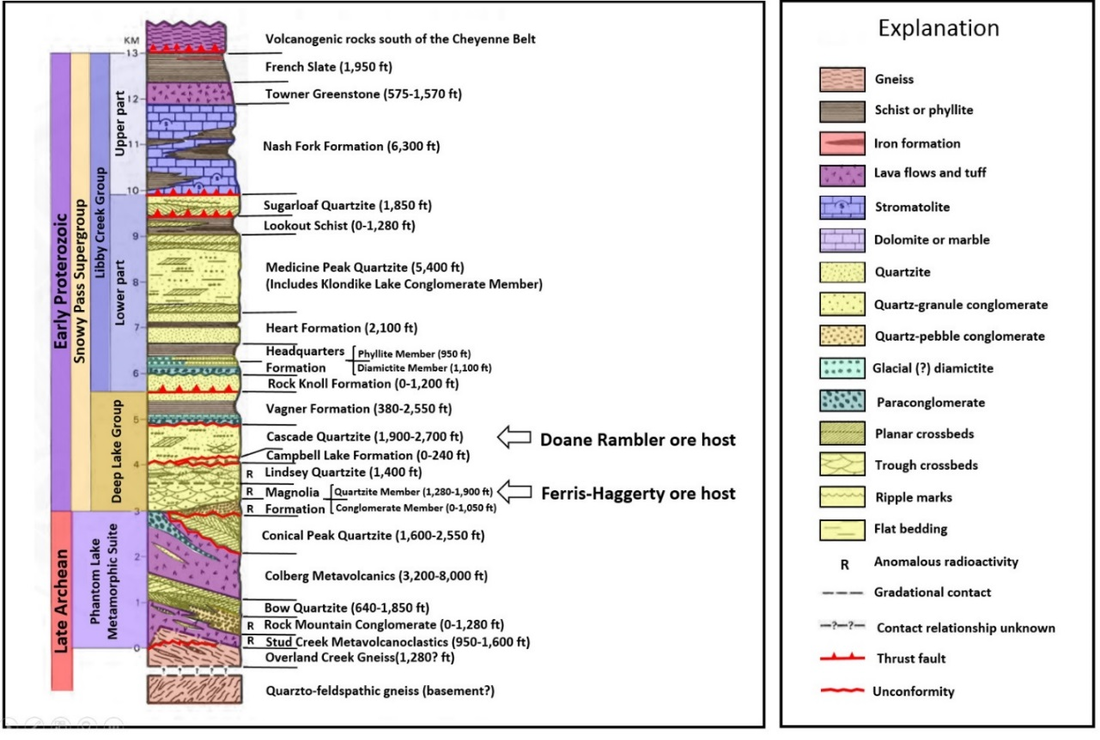

Stratigraphic column of Precambrian metasedimentary and metavolcanic rocks, Encampment area, Sierra Madre Mountains, Wyoming.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1993, Guide to the Geology, Mining Districts, and Ghost Towns of the Medicine Bow Mountains and the Snowy Range Scenic Byway: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular No. 32, Fig. 2, p. 5; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/guide-to-the-geology-mining-districts-and-ghost-towns-of-the-medicine-bow-mountains-and-snowy-range-scenic-byway-1993.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1993, Guide to the Geology, Mining Districts, and Ghost Towns of the Medicine Bow Mountains and the Snowy Range Scenic Byway: Wyoming State Geological Survey Public Information Circular No. 32, Fig. 2, p. 5; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/guide-to-the-geology-mining-districts-and-ghost-towns-of-the-medicine-bow-mountains-and-snowy-range-scenic-byway-1993.

The Proterozoic units that lie on crystalline basement north of the shear are a clastic wedge that is over 42,000 feet thick. They are divided into four sedimentary cycles each having a conglomeratic base and fine upwards. The metamorphosed rocks include conglomerate, quartzites, phyllite, limestones, dolomites and minor volcanics deposited in marine and terrestrial environments. South of the Cheyenne belt are an assortment of deeper marine schists and gneisses of metavolcanic and metavolcanoclactic rocks of an island arc. The ore north of the suture are massive sulfide deposits within quartzite of the Deep Like Group. Minor stratiform volcanogenic sulfide deposits occur south of the Cheyenne Belt in the Green Mountain Formation.

The Doane Rambler and the Ferris-Haggerty were the two most important mines in the district. The Doane Rambler was opened in 1895 at NE/4, Section 25, Township 14 North, Range 86 West in Battle Lake basin. The host rock (Cascade Quartzite) is oriented east-west and dips at 65 to 75 degrees north. Host rock is a brecciated quartzite in the upper part of the Deep Lake Group.

The Doane Rambler and the Ferris-Haggerty were the two most important mines in the district. The Doane Rambler was opened in 1895 at NE/4, Section 25, Township 14 North, Range 86 West in Battle Lake basin. The host rock (Cascade Quartzite) is oriented east-west and dips at 65 to 75 degrees north. Host rock is a brecciated quartzite in the upper part of the Deep Lake Group.

Ore sample from Rambler mine.

Image: After McAvoy, J., No Date, Chalcocite, Rambler Mine; https://www.mindat.org/locentries.php?m=962&p=4227.

Image: After McAvoy, J., No Date, Chalcocite, Rambler Mine; https://www.mindat.org/locentries.php?m=962&p=4227.

Doane Rambler Mine workings: (A) cross sectional view, (B) plan view. Numbers are locations of (1) discovery, (2-6) main ore shoot at different levels, (7-10) additional ore shoots on the 115 foot level, and (11) copper-stained fissure in quartzite. Stopes are shown by blue-green color.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig. 6, p. 14; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/mineral-deposits-of-the-encampment-mining-district-sierra-madre-wyoming-colorado-1986/.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig. 6, p. 14; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/mineral-deposits-of-the-encampment-mining-district-sierra-madre-wyoming-colorado-1986/.

The Ferris Haggerty Mine was the most productive copper mine in the district. The mine was opened as the Rudefeha mine in 1897 at se/4 ne/4, Section 16, Township 14 North, Range 86 West. The mine was about 16 miles west of Encampment on the west side of the Continental Divide at an altitude of 9,888 feet. The ore was hauled 60 miles by wagon to the nearest Union Pacific rail junction then shipped to a smelter in Chicago. The ore is hosted by the Magnolia Quartzite Member of the lower part of the Deep Lake Formation. A 20 foot copper vein lies in a brecciated quartzite that is in contact with a hanging wall schist. The ore bed dips 30 to 60 degrees south and is 250 to 300 feet long. The mine closed in 1908 but the ore was not played out. The Ferris-Haggerty Mining Corporation of Colorado purchased the abandoned mine in 2015 with plans to renew operations. The company estimated the mine contains up to 95 percent of the original copper in place (928,500 tons) with 116,000 ounces of gold in reserve.

Ore sample from Ferris-Haggerty mine.

Image: After Hausel, D.W., 2010, The Ferris, Haggarty Copper-Gold mine, Encampment District, Wyoming: GemHunter Blog;

http://ferris-haggarty.blogspot.com/2010/08/ferris-haggarty-copper-gold-mine-grand.html.

Image: After Hausel, D.W., 2010, The Ferris, Haggarty Copper-Gold mine, Encampment District, Wyoming: GemHunter Blog;

http://ferris-haggarty.blogspot.com/2010/08/ferris-haggarty-copper-gold-mine-grand.html.

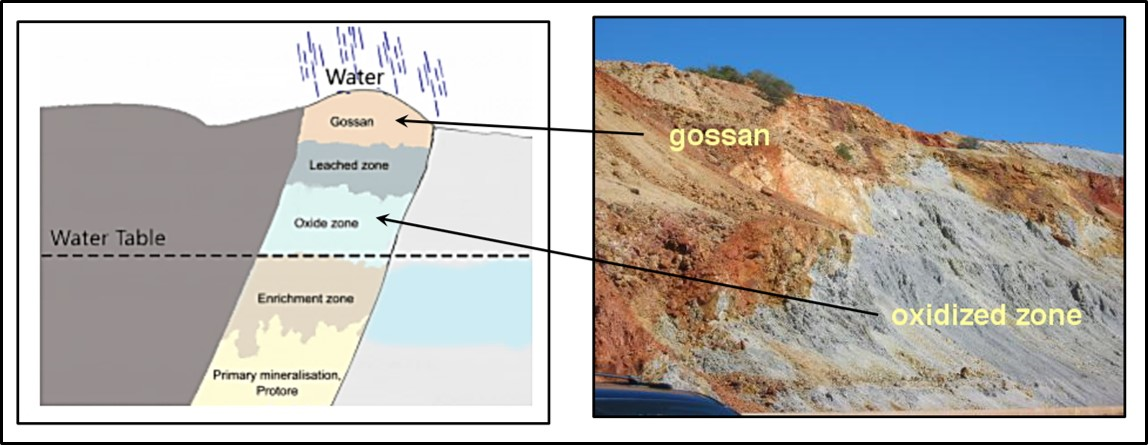

The Ferris-Haggerty workings parallel to the strike of the ore body. Gossan (see diagram below) is as an intensely oxidized, weathered or decomposed iron bearing rock capping over a sulfide deposit. Stope is an open space in a mine left after removing the ore.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig.8, p. 17; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/mineral-deposits-of-the-encampment-mining-district-sierra-madre-wyoming-colorado-1986/.

Image: After Hausel, W.D., 1986, Mineral Deposits of the Encampment Mining District, Sierra Madre, Wyoming – Colorado: Wyoming State Geological Survey Report of Investigations No. 37, Fig.8, p. 17; http://sales.wsgs.wyo.gov/mineral-deposits-of-the-encampment-mining-district-sierra-madre-wyoming-colorado-1986/.

Diagram of a sulfide deposit with a porous gossan cover. Gossan outcrops often stand out in relief in arid and semi-arid climate of the Rockies and are often called an “Iron hat.” Image on left is an outcrop at Lavender Pit overlook, Bisbee, Arizona.

Image: Left: Geology Universe; Right: https://uwaterloo.ca/wat-on-earth/news/oxidized-zone-minerals.

Image: Left: Geology Universe; Right: https://uwaterloo.ca/wat-on-earth/news/oxidized-zone-minerals.

South aerial view of Encampment, Wyoming.

Image: https://www.wyomingcarboncounty.com/places-to-visit/encampment.

Image: https://www.wyomingcarboncounty.com/places-to-visit/encampment.

Encampment served as a site for hunting and fishing for centuries. With the coming of European trappers, the area took on the name Camp le Grande. Mining began in the latest 19th century for the base metal resource found in the Sierra Madre. The mining boom lasted only ten years (1897-1909), but ranching continued to flourish in the lush valleys. Today Encampment serves as a portal to the Medicine Bow forest and the Sierra Madre mountains. It remains a gateway for year-round outdoor adventure.

The material on this page is copyrighted